FREE FLOW OF INFORMATION

An article by Colleen Wood and Alexis Lerner in Waging Nonviolence published on March 21

As the Kremlin cracks down on antiwar protests, subversive street art critiquing the war in Ukraine is proliferating across Russia.

It is exceedingly difficult to organize peaceful protests in Russia. Since the Kremlin’s “Special Operation” began on Feb. 24, police have detained nearly 15,000 people across the country in connection with peaceful demonstrations. On March 4, the Kremlin expanded the scope of illegal activity with two laws that criminalize war reporting and antiwar protest. As of March 15, 180 charges have been lodged against protesters. Given — or despite — these restrictions, activists and artists are turning toward more subtle and subversive tools for political expression: namely, graffiti.

Spray-painted on a snowbank in the Russian city of Perm, this graffiti reads “Stop bombing Kharkov.” (Twitter/@RusMilkshake)

In the last 20 years, the Kremlin has limited free speech and citizens’ right to public assembly. While Russia has not been a democracy for many years, the Putin regime has generally avoided the Soviet approach to censorship, instead permitting some degree of political expression. In recent years, there have been calls for nuclear disarmament, environmental protection, maintaining pensions, and better treatment of LGBT communities. The precedent has been to criticize policy, not Putin.

But authorities are quick to crack down when citizens cross “red lines” of criticism on taboo topics like corruption and Chechnya, a republic in the North Caucasus where Moscow led two wars in the last 30 years. However, just because people cannot safely or legally speak out against unfavorable policies does not mean that they remain silent.

In order to circumvent this control over free speech and assembly, Russian activists and artists use spray paint to share anonymous and subversive views on a city’s walls. While this art form has existed in the region since the 1970s, it took a distinctly political turn in the early 21st century. Today, graffiti is an effective form of anonymous and accessible political critique, functioning as a “canary in the coal mine” when it comes to sharing otherwise privately-held political discontent.

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on Feb. 24, there has been a resurgence of politically subversive graffiti that the state has spent the last 10 years trying to crowd out of public spaces.

Spray-painted tags with a simple message — “No to War!” — appeared as early as Feb. 25, even before the first major antiwar demonstration in Moscow. This same message has been painted in metro stations, schoolyards and pedestrian thoroughfares in Moscow and St. Petersburg, which are Russia’s biggest cities and have traditionally been the hub of political dissent, as well as in smaller towns including Lipetsk, Irkutsk, Samara and Tomsk.

In addition to the ubiquitous, scrappy “No to War” tags, artists are painting more sophisticated pieces with targeted critiques of Putin and the regime. In Moscow, for example, an anonymous artist used a stencil to write “You’re carrying us to hell” in Russian, implying that the Kremlin is dragging the country into an undesirable conflict and, subsequently, unwanted hardship for attacked Ukrainians and sanctioned Russians. Other anonymous works stress in all-caps that “Putin is an aggressor” and “Kremlin thieves need the war, but not me or you.” The latter, in particular, implies that the Putin regime benefits from its war in Ukraine, either through the capture of warm water ports on the Black Sea, the installation of a pro-Kremlin puppet government in Kyiv or by pocketing profits from military contracts.

Authorities are struggling to paint over the proliferation of antiwar tags across the country. But street art is not always painted with a spray can. Other media include stickers, stencils, moss, snow, yarn-bombing and wheat-pasted posters.

(Continued in right column)

Can the peace movement help stop the war in the Ukraine?

Can popular art help us in the quest for truth and justice?

(Continued from left column)

In Krasnoyarsk, Vera Kotova etched “No to War” in snow that had gathered on a statue of Vladimir Lenin. She was promptly charged under the new law criminalizing antiwar protest. She faces a fine of 30,000 rubles, about $290.

Activists also leverage visual irony to critique censorship and the political environment in Russia. One placard on the back of a bus stop in St. Petersburg graphs “fear” against “hope” in Russia since 1983, with hope surging in 1991 as the Soviet Union collapsed and again in 2012 following massive protests. While the piece — installed by the Yav crew, whose name comes from the Russian word for “reality” — does not specifically mention the war, it is heavily implied.

In Nizhny Novgorod, police dragged a woman holding a blank placard in the city’s central square. One video, viewed 1.1 million times on Twitter, shows people in the crowd asking the police to justify the detention.

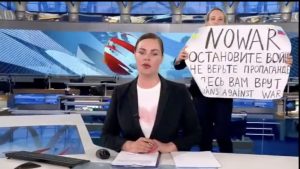

In addition to capturing moments of state violence or mass mobilization, activists are also taking advantage of digital communications to criticize the war and mobilize nonviolent demonstrations.

Post Tribe Inspiration created a virtual gallery on Red Square, home of the famous St. Basil’s Cathedral, as part of their ART NOT WAR campaign. Users can visit the Metaverse through the Spatial app to view a virtual antiwar art exhibit, filled with doves and peace signs drawn in blue and yellow, the colors of Ukraine’s flag. Users are invited to add their own pieces to the online gallery.

Other works integrate virtual and real-life spaces through weblinks and QR codes that can direct a viewer to a particular website with their cell phone camera. In St. Petersburg, an anonymous “lost dog” sign appeared in the metro, describing a search for a pet named Peace. The sign reads, “On February 24, an unpleasant man with hints of Botox stole our Peace!” The sign has a QR code that links passengers to resources to “help return peace,” which actually directs to a petition on Change.org demanding an end to the war in Ukraine.

Before it was banned on March 14 in Russia, activists leveraged Instagram’s emphasis on images to spread information about protest logistics. One Instagram post informed Muscovites of a protest on Feb. 24 without specifying any details in text. The caption insists, “This is just a pretty picture,” and the image features a sketch of famous poet Aleksandr Pushkin and the number seven surrounded by an emoji of a walking man. Politically motivated followers had to solve the rebus to figure out where and when the demonstration was happening. The walking emoji nods to the coded language of “taking a walk” to protest, the portrait of Pushkin leads people to Pushkin Square, an open pedestrian space in central Moscow, and the number seven is a sign to show up at 7 p.m.

Social media also enables activists to mobilize sympathetic minds and atomize dissent. The hashtag #тихийпикет — “quiet picket” in Russian — has more than 1,600 posts on Instagram, including posts that instruct social media users how to participate in single-person antiwar demonstrations. Photos with the hashtag show subtle symbols of dissent, including masks and tote bags with the “No to War” slogan painted on and green ribbons.

These kinds of subversive and coded emblems of dissent mirror past tactics. In 2012, passersby might have been informed of a St. Petersburg protest through stickers on lampposts, such as the one showing then-St. Petersburg Mayor Valentina Matvienko being trampled by Peter the Great on horseback next to the time and location of the meeting.

These more subtle tactics were more commonplace in the years when Russia’s activist circles and political opposition lacked centralized leadership. Alexei Navalny emerged as a central figure in late 2011, and over the last decade, his team has played a crucial role in organizing large gatherings against corruption, pension reform and environmental degradation. But Navalny was poisoned and imprisoned last year, and on March 15 a court extended his sentence by 13 years. This dismantling of organized opposition makes it even more difficult to organize mass demonstrations in the streets.

The arrest of 15,000 protesters, independent journalists, opposition politicians and graffiti artists has significantly raised the stakes for dissent. Some graffiti artists have responded to this by going into the shadows, painting critical works in abandoned buildings and on the outskirts of town to avoid detection. Others have chosen to leave Russia altogether.

Despite the repression and hollowing out of Russia’s graffiti and activist communities, artists continue to innovate to publicize their critical views on the Kremlin, its violation of individual rights and its war in Ukraine. This is key in demonstrating to others around the country — and around the world — that dissent of Putin’s leadership is still alive.