. . SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT . .

An article by Rodrigo Guillot / Globetrotter from Scoop Independent News (reproduced as creative commons – no commercial purpose or end)

In 2010, Cuba’s former President Fidel Castro said: “López Obrador will be the person with the most moral and political authority in Mexico when the system collapses and, with it, the empire.” He was referring to Andrés Manuel López Obrador (known as AMLO), who is the current president of Mexico and head of the Morena (National Regeneration Movement) political party.

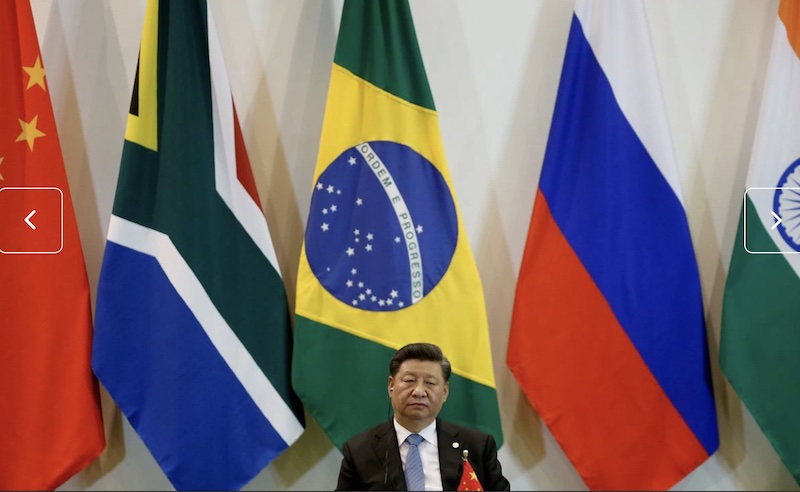

Photo by Edgard Garrido / Reuters

Despite the wide lead he had in all the polls before the elections, López Obrador’s victory in 2018 took almost everyone by surprise. Even the Morena militants remained doubtful for some days, since the dynamics of electoral fraud in Mexican politics had made defeat seem inevitable.

Few of us knew what to expect from Mexico’s new government since AMLO is the first leftist president in our country’s modern political history. The first two years of his term were marked by the absence of any concrete foreign policy, at least publicly. The theory that the best foreign policy is domestic policy led President López Obrador to concentrate his efforts on trying to solve the larger problems being faced by the Mexican people, as well as dealing with former U.S. President Donald Trump’s aggressive anti-immigration policy that was mainly directed toward the Mexican migrant population entering and already in the United States.

Fourth Transformation

The only noteworthy Mexican public diplomacy initiative undertaken by López Obrador during the first three years of his six-year term was to advocate for the Comprehensive Development Plan for Central America. This plan was developed by El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico and the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). President López Obrador’s government began working on the plan from the day he took office. The initiative addressed both issues, the attacks faced by migrants from Central America in the United States and the real needs of the people who are compelled to migrate to other countries from the region. The structural causes of migration—poverty, inequality and insecurity—framed the discussion by the stakeholders who worked on finalizing the initiative. The plan challenged the U.S. border security doctrine, which treats socioeconomic problems as military problems.

The triumph of Morena in one of Latin America’s largest countries opened a cycle of hope among progressive forces in the region; Latin American leaders and intellectuals have spoken of Mexico as the epicenter of the new progressive wave in the hemisphere. But Morena’s triumph was met by three complexities. First, the difficulties being faced by López Obrador as he has tried to lay the foundations for national development and address the glaring inequalities in the country (10 percent of Mexicans hold 79 percent of its wealth); this included a national project to end inequality and discrimination, which would be funded by the revitalization of the oil industry, the nationalization of lithium, and the implementation of various infrastructural works.

Second, because the pandemic accelerated the process of the neoliberal crisis at a global level, including in Mexico, López Obrador has spoken about the need to “end” neoliberalism by 2022 in the country.

(article continued in right column)

Can Latin America free itself from US domination?

(article continued from left column)

Third, there has been a renewed aggression by the United States through its blockades and sanctions campaigns against several Latin American countries, including Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela. López Obrador’s fourth transformation (4T), which is the name of his political project—referring “to a moment of change in the political system”—has led to disputes with the U.S. government and U.S.-controlled institutions (including the Organization of American States). This is what gradually drew Mexico’s government into a more prominent role in the Americas.

López Obrador’s Public Diplomacy

The increase in López Obrador’s activity relating to international diplomacy has been gradual and well-calculated. López Obrador gradually introduced some of these foreign policy matters into the arena of national political debate before he tested the waters in the region with them. Each morning he holds a press conference, where many of these ideas are first introduced. López Obrador’s commitment to building a revolution of conscience has transformed Mexican diplomacy into a public phenomenon.

Before López Obrador, foreign policy matters were discussed behind closed doors. Now, López Obrador uses his press conference to provide the public with the historical and political reasons for Mexico’s position on, for instance, the U.S. blockade of Cuba and its economic war against Venezuela, the violent anti-immigrant policy of the United States and the war between Russia and Ukraine. Because López Obrador has tried to explain the reasons for the diplomatic decisions taken by Mexico regarding various global matters, it has helped build a consensus among large sections of the population for these decisions, including the most recent decision taken by him to not attend the Summit of the Americas.

Summit of the Americas

United States President Joe Biden announced in January that the United States and the Organization of American States (OAS) would host the Summit of the Americas in Los Angeles from June 6 to June 10. López Obrador toured Central America and the Caribbean, which ended in Cuba, before the summit. During the tour, López Obrador developed Mexico’s position on the summit. This viewpoint was also apparent earlier when Mexico hosted the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) summit in September 2021, where Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela were able to participate—unlike during the Summit of the Americas where these countries were banned from attending the event. At that 2021 summit, López Obrador proposed to shut down the OAS and replace it with “a block like the European Union,” such as CELAC.

Before the Summit of the Americas began, López Obrador announced that Mexico would not attend it because of two principles of Mexican foreign policy: First, the United States’ decision to not invite Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela violated the principle of non-intervention in the internal affairs of other countries. Second, the principle of legal equality of all countries should allow all people to be represented at the international level through their governments. López Obrador’s decision to withdraw from the summit surprised both Washington and Latin American capitals; his decision was followed by both Bolivia and Honduras and was backed up by countries such as Argentina.

Biden, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken and U.S. Ambassador to Mexico Ken Salazar, meanwhile, tried to negotiate to ensure the presence of the Mexican president at the summit, but without any success. The hegemony of the OAS had begun to decline after the CELAC summit in 2021 but seems to have reached its end with these latest developments during the Summit of the Americas in Los Angeles.

But the more important outcome of the summit was the reaction of the different Latin American leaders who joined Mexico’s show of dignity and displayed the strength of popular power and assumed positions of support for a new form of regional organization, which does not require the support of the United States. The general mood in Latin America is that the U.S. should not waste its time interfering south of its border but should, instead, spend its energy trying to resolve its cascading internal crises.