DISARMAMENT & SECURITY .

An article from The Conversation

The election of Iván Duque four years ago was a threat for us. But we will continue to follow the peace agreement regardless of who is the next president of Colombia. We are more determined than ever to comply with the peace accords, and this is the reason they want to kill us.

Olmedo Vega spent 35 years as a guerrilla commander during Colombia’s armed conflict – one of the longest the world has ever seen. “The FARC is my family – I grew up with the guerrillas. But now I really want to commit to this new life here in Agua Bonita, along with my old comrades.”

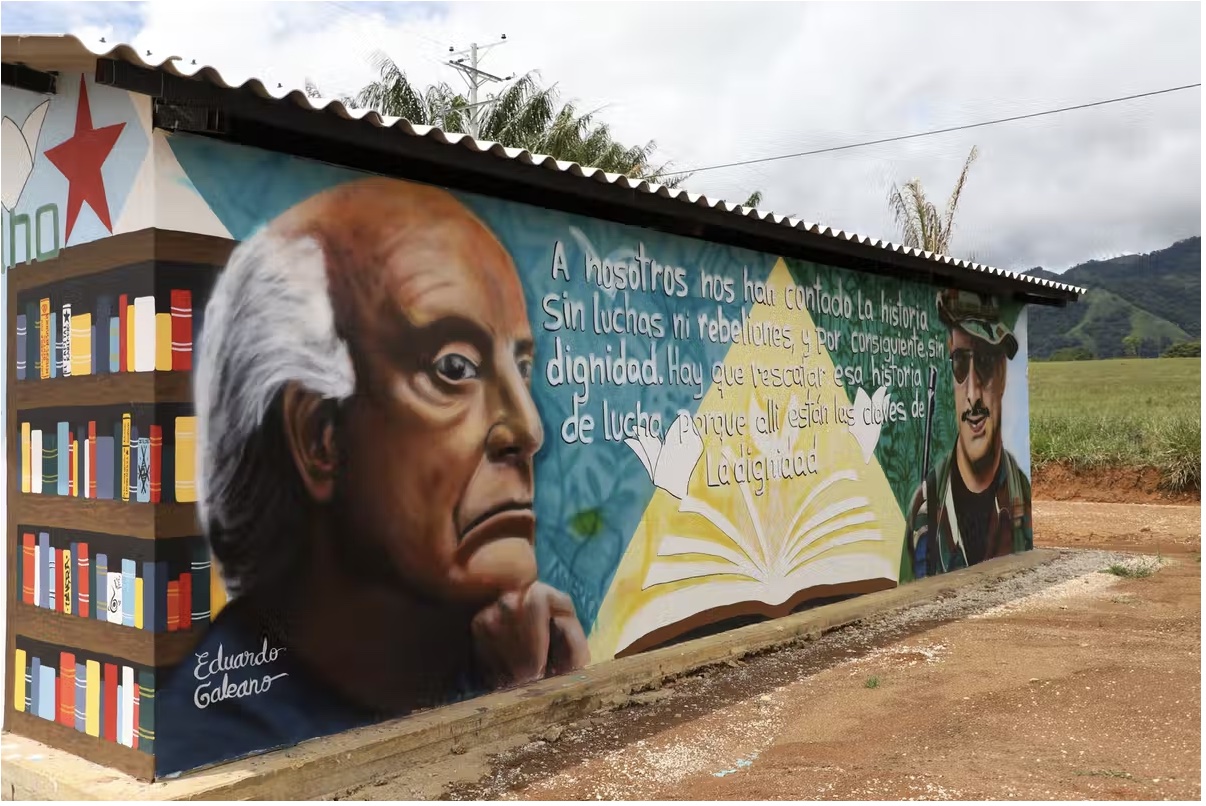

One of the many thought-inspiring murals painted on the houses of Agua Bonita. Photo: Juan Pablo Valderrama. Author provided

Over the past four years, we have carried out 42 in-depth interviews with former guerrilla soldiers in Agua Bonita and some of the other 25 Territorial Spaces for Training, Reintegration and Reincorporation (ETCR in Spanish), developed by the Colombian government and the UN to resettle thousands of former FARC fighters after the historic 2016 peace agreement.

We sought to understand the barriers faced by ex-combatants as they try to reintegrate into civil society. With President Duque’s reign almost over and his successsor due to be elected on June 19, the result has major implications for the future of Colombia, the survival of the peace agreement, and the prospects of all those former combatants who have committed to a life without conflict.

After six decades of fighting, it is estimated that almost 20% of the population is a direct victim of Colombia’s civil war – including almost 9 million internally displaced people, 200,000 enforced disappearances, up to 40,000 kidnappings, more than 17,000 child soldiers, nearly 9,321 landmine incidents, and 16,324 acts of sexual violence.

For the almost 13,000 former FARC guerrillas, the end of the conflict initiated a process of “disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration” into Colombian society. But while positive steps were taken on both sides, more than 300 massacres have been recorded since the peace deal was signed on September 26 2016. Some 316 FARC ex-combatants and 1,287 human rights defenders have been murdered during this period of “peace”, putting the agreement under increasing threat.

‘A place to have a dignified life’

The Agua Bonita (“Beautiful water”) guerrilla demobilisation camp is located on a small plateau on the edge of the Amazon basin, about an hour’s bumpy drive from Florencia, capital city of the Caquetá department in Colombia’s Amazonía region.

Since 1970, Caquetá had been the headquarters for both FARC and the guerrillas of the Popular Liberation Army (EPL). It is a geographically strategic corridor for illicit drug trafficking (particularly related to the production of cocaine), the transport of illegal weapons and the smuggling of kidnapped people. It is also one of the first places where guerrilla groups used landmines to wrest territorial control from the Colombian army.

In 2017, when ex-FARC combatants first arrived in the empty area where Agua Bonita now stands, they worked with local builders for seven months to construct 63 houses using glass-reinforced plastic and average-quality plywood. Local workers from Florencia and the nearby towns of Morelia, Belen de los Andaquíes and El Paujil helped them build the camp.

“At the beginning, it was difficult to work side-by-side with the local builders because of our stigma as guerrilleros,” recalled Federico Montes, one of the community leaders. “But after six months of working with us every day, a couple of them moved with their families to live here!”

Agua Bonita is situated amid one of the most biologically diverse terrestrial ecosystems in the world; home to around 40,000 plant species, nearly 1,300 bird species and 2.5 million different insects. Red-bellied piranhas and pink river dolphins swim in the waters here – yet in both 2019 and 2020, Colombia was named the world’s deadliest country for environmentalists by human rights and environmental observers Global Witness.

According to Montes, Agua Bonita’s high year-round temperatures and humidity mean “the weather is perfect to grow yucca, plantain, cilantro and pineapple. And if you are feeling more adventurous, you can have trees of araza, copoazu, yellow pitaya and other Amazonic crops. We are in the middle of a fruit heaven here.”

The community started with a population of more than 300 ex-FARC combatants. These days, it boasts a library with 19 computers and four printers, a bakery, convenience store and restaurant, a football pitch, health centre and community centre with a daycare facility for toddlers. Former combatants farm eight hectares of pineapple cash crop and have their own basic processing plant for fruit pulp. They also have six 13-metre-long fish tanks, a big hen house and dozens of large communal gardens.

One of the main attractions for visitors is the vibrant murals painted on the 65 modest houses, portraying everything from local flora and fauna to guerrilla leaders and FARC paraphernalia. The most recurring features are the words “peace”, “reconciliation” and “hope”.

“Our main aim,” said Montes, “is to create a place to have a dignified life, where all together can be free, safe and secure, living in proper houses with access to health, employment, and education.”

Yet since the establishment of Agua Bonita in 2017, 29 ex-combatants have been killed in the area. According to Olmedo: “During the government of Duque, there has been a shortage of food, goodwill and economic support in Agua Bonita – a total lack of governmental support. But the presidential elections are giving us hope for a better future.”

‘A lot of stigmas and negative attitudes against us’

In the run up to his election in June 2018, Duque, as leader of the right-wing Centro Democrático party, fiercely opposed the peace agreement with the FARC, vowing to renegotiate what he described as a “lenient” deal while pledging not to “tear the agreement to shreds”.

After four years in charge, Duque – Colombia’s least popular president in polling history – has undermined the implementation of the peace agreement, and further polarised the country and its politics. Levels of respect for human rights, security, quality of life and poverty have all worsened under his militaristic tenure.

Olmedo Vega, 49, has lived in Agua Bonita from its earliest foundations. When we met him, Vega was taking part in a video letter exchange project with young people from Medellin, Colombia’s second-largest city. “Some of the questions from these students were really difficult to answer,” he told us. “There are a lot of stigmas and negative attitudes against us as ex-FARC members. ‘Terrorist’, ‘murderer’, ‘killer’, ‘scumbag’ … these are the words some people used to introduce me.”

But these days, Vega is proud to call himself a student too. One evening, during dinner, he asked us: “What did the arrival of an American astronaut on the Moon mean politically?”

As we fumbled for an answer, he interrupted to say: “I am studying four hours every day to get my qualifications: two hours in the morning, two in the afternoon. We are 30 comrades working so hard to sit the ICFES (Colombian A-level exams) next September. This is why I believe in the peace process, because now we have the opportunity to study. I want to be a doctor in the future, this is my dream. I want to help people, and to build a more equal society in Colombia.”

That evening, Vega offered us cancharina for pudding and the sugar cane drink by paramilitary groups in 2021.

“Jorge was my pal. He taught me how to be a good guerrillero, a good comrade. He strongly believed in the power of peace and reconciliation. I cannot understand why he was assassinated in front of his family in that bakery.”

Expressed as a cold statistic, Garzón was ex-combatant no.290 to have been murdered since the signing of the peace agreement. The political assassination. Francia Márquez, a black environmentalist, also received death threats.

Petro led the presidential election first round on May 29 with 40% of the votes. His rival in the run-off on June 19 will be Rodolfo Hernández, a businessman-politician who is viewed as a right-wing conservative and populist outsider.

Colombia is the only major country in Latin America that has never had a leftist leader. The country’s right-wing parties and liberal establishment appear determined to maintain this record, amid campaigns that have been regularly accused of racism, sexism and classism against Márquez in particular.

Yet according to a recent survey, 79% of Colombians believe the country is on the wrong track. Political parties have a collective disapproval rate of 76%, with the Colombian Congress only marginally less unpopular.

The successful reintegration of thousands of ex-FARC guerrillas into civil society remains one of many daunting challenges for the next Colombian government. Reintegration problems encountered by ex-combatants worldwide have included a lack of educational opportunities, the absence of suitable career options and insufficient psychological support.

In Colombia, we have identified three crucial aspects that are challenging successful reintegration for FARC ex-combatants: a lack of participation in the civilian economy, a lack of access to educational opportunities, and a failure by the authorities to exercise “equal citizenship” that guarantees social and civic reintegration.

At stake is the entire future of the peace agreement, and with it, prospects for reducing poverty, inequality and other dynamics of economic exclusion. Three generations of Colombians do not know what it means to live in a peaceful society. The reintegration of ex-combatants is crucial to building a general understanding that reconciliation is key to creating a new Colombia, where violence is not the answer to overcoming your problems.

‘The stigma makes it impossible to get a job’

The access road to Agua Bonita is not easy. There is no public transport, and the roads are extremely precarious. The poor transport infrastructure of Caquetá in general severely hampers the productivity of this region.

(Article continued in right column)

What is happening in Colombia, Is peace possible?

(Article continued from left column)

While the camp – which operates entirely as a cooperative – has not suffered from trade boycotts, unlike some other reintegration camps, raw materials can take months to arrive here. And the twin spectres of discrimination and unemployment loom large over residents here.

“I have plenty of stories of people saying to me: ‘You cannot get a job because you don’t deserve it, just get out of here,’” Vega told us. “I have to fight against this stigma every day, and it is worst when I have to apply for a job because sometimes people have the wrong idea about us. I am a proud ex-combatant that just wants the peace of Colombia and a decent job!”

Daniel Aldana is one of the youngest ex-combatants living in Agua Bonita. He has been trying to get a job since 2019 but, due to the extent of criminalisation and stigmatisation of ex-FARC guerrillas in the region, he said it is almost impossible for him even to secure an interview.

“When the employers saw my identity card had been issued in La Montañita [the nearest town to Agua Bonita], they said I needed to have a ‘special selection process’. That means they will double or triple-check with the authorities if I have a police record or if my name is on a terrorist database list. If you say you are from Agua Bonita, the people say you are a terrorist. This stigma is making it impossible to get a job here.”

Aldana is not alone. Jorge Suarez, a builder who spent more than 13 years as a FARC commander, recalled going for a job interview in Florencia. “It was so humiliating. ‘Assassin’, ‘murderer’ and ‘scumbag’ were just a few of the words the people at the recruitment agency used to refer to me. Never again.”

Suarez added: “The problem is that people don’t trust us. We have done everything to show that our intentions for a peaceful future are real, yet so far we are getting only two things back: no proper jobs, and tons of bullets.”

Such experiences are not unique to ex-combatants living in Agua Bonita. Esteban Torres, a former guerrilla doing his reintegration in the Pondores camp (ETCR Amaury Rodríguez) in La Guajira, told us he had experienced the same negative reaction.

“In Riohacha City, when I was looking for a job, the people said to me: ‘Well, you look like a nice bloke, but you have blood on your hands. You will never have a job here because you have the blood of innocent people on your hands, and you are a terrorist – a disgrace.’”

Torres continued: “That is when you realise that this is a long-term process. We need a process to remove the stigma against us from Colombian people’s hearts.”

Lessons from Northern Ireland

As well as our interviews with former guerrilla soldiers in Colombia, we also conducted 12 in-depth conversations with ex-combatants in the conflict known as The Troubles. Despite Northern Ireland’s peace agreement having been in place for nearly a quarter of a century – and the country’s very different societal context – we found many of the raw grievances raised by ex-FARC combatants mirrored by these former political prisoners in Northern Ireland, all of whom asked to remain anonymous.

While we heard common themes expressed by loyalist and republican interviewees alike, we highlight some republican voices here as these ex-combatants were dedicated to a form of counter-state insurgency that resembled the aims of the FARC’s armed struggle against the Colombian state.

One former member of the Provisional Irish Republican Army, (P)IRA, spoke about his difficulties finding meaningful employment, despite the fact that he had gained educational qualifications during his time in prison. “I could only get low-level jobs. In prison I had studied so I had qualifications, but I was still only working as a kitchen porter or doorman.

“No one would employ an IRA guy,” he continued. “In one job, I was asked to leave because people found out about my past. They weren’t comfortable working with me any more.”

Another ex-(P)IRA combatant explained the complexity of simply filling out a job application form. “A job application asks: ‘Do you have a criminal record?’ If we say ‘no’ because we claim we don’t have a criminal record – we are not criminals – then we have lied and can be dis-employed, which has happened to many people. But if we say ‘yes’, then we will not get through the vetting procedure.”

Our interviews also highlighted a common resentment about the forms of legally structured discrimination that former combatants in Northern Ireland have experienced.

“We can be stopped from travelling to certain places, and certain jobs are completely off limits to us,” explained another ex-(P)IRA member. “Even our ability to spend money is restricted; we can’t purchase home insurance and car insurance. It’s an inhibitor. We can’t get business loans … It all adds up to making things more difficult for us than for everyone else.”

Many of our interviewees had either worked or volunteered for community-based organisations that sought to diffuse inter-community tensions in Northern Ireland, and to steer young people away from participation in violence. In general, an incredibly small number of ex-political prisoners on both sides have returned to political violence, and very few have been convicted for other forms of violent criminality. Yet despite this, the loyalist and republican ex-combatants we spoke to complained of being largely denied equality of citizenship, and still face blockages to participation in the civilian economy.

‘Society resents us’

More than a decade ago, Esperanza* served as a commander and learned about equal rights as she fought side-by-side with the FARC men. But as soon as she stepped into civilian life, she told us she lost her autonomy again.

“Historically, this is a patriarchal culture. Those of us who go to war break traditional roles and stereotypes set for women, so society resents us. I used to give orders and command 100 armed men, and now they are expecting me to do a cooking course! What the hell?”

Problems highlighted by Esperanza and Tania Gomez, another female ex-combatant living in Agua Bonita, include an absence of suitable career options for women, and a lack of psychological support and understanding of their needs and interests following the war. Such concerns are leading female ex-combatants to drop out of the reintegration programmes.

When the Colombian Reintegration Agency offered Gomez the chance to do a sewing and childcare course, she recalled saying to the official: “Are you kidding me! After 10 years of fighting against the Colombian Army every day, you want me to open a kindergarten? I didn’t join FARC to become a substitute mother, I am a revolutionary!”

For female ex-combatants, after long years as a fighter, the idea of “mainstream” family life can be very unappealing. “What would my life be like in the future if I follow this path?” Esperanza asked us. “Just at home with a husband, kids and playing ‘happy house’ forever? No way! I wouldn’t last a day doing that!”

The reintegration process has clearly failed to achieve genuine gender inclusiveness. When we asked Nelcy Balquiro why she joined the FARC 11 years ago, she said without hesitation: “I wanted to change the world and become somebody. I wanted to be part of something important. My dream now as a civilian is to empower everyday women about their rights and fight this patriarchal system. As a female ex-FARC commander, this is now my more important political mission.”

Discussing the wave of violence that is killing ex-combatants, Balquiro countered immediately: “Nobody says anything about the murdered females – once again the spotlight is on men! Nobody is saying a word about Maria, Patricia, Luz and the other 10 women who have been murdered [since the peace agreement] – it is shameful.”

Balquiro wants to fight for equal pay and the right to work outside the home. She argued that “feminism is a main part of being a female ex-combatant. We are fighting now for Colombian women to have freedom from abuse and male exploitation.”

‘We are dreaming of peace’

Colombia’s outgoing leader Iván Duque will be widely remembered as a president that did nothing to implement the peace agreement. Colombia’s election now offers a critical opportunity to address the problems amplified by four years of governmental neglect and lack of political will.

Simón* is a FARC ex-combatant living in the Icononzo camp (ETCR Antonio Nariño) in the Andean region of Tolima. “I don’t want to live in fear for another four years,” he said.

“The feeling that paramilitary soldiers can kill you at any moment, working in alliance with the actual government, like what happened in Putumayo recently … it’s becoming unbearable. This presidential election is the opportunity to build new roads, new ways, and leave the torturous one that we are having now.”

According to Esteban Torres from the Pondores camp: “The implementation of the peace process is similar to [Colombia’s traditional festival], Barranquilla’s carnival. Those who live it, enjoy it – and we want to continue the party. [Our goal] is not just to stop killing each other any more in Colombia; it is about creating a new culture of peace, a new rhythm.

“Duque almost killed the party. He didn’t know how to dance along with people that don’t like guns and his extreme-right perspectives. He just likes the rhythms of war. But now we have the opportunity to start tuning good vibes once again and change our future as new citizens of Colombia. My hope is to restart the party!”

Over the six-decade conflict, the Colombian state helped to create and sustain an image of FARC combatants as bloodthirsty barbarians. The new government will need to take brave and imaginative steps to break down these deep-rooted conceptions. There have already been some important initiatives, such as the letter exchanges between former FARC combatants and Colombian civilians. However, much more must be done if the Colombian state is to avoid the long-standing forms of discrimination still being expressed by ex-political prisoners in Northern Ireland.

It’s also important, in time, to remove legal barriers to equality of citizenship. Understandable measures taken in the immediate aftermath of the conflict, such as the need to carry forms of personal identification that highlight an ex-combatant’s background, need to be subject to sunset clauses – to be lifted, for example, if an individual has met certain requirements that demonstrate their dedication to peace. Similarly, criminal records directly related to participation in the conflict might also be erased once ex-combatants have demonstrated their commitment to the agreement.

In addition, former combatants need to feel some control over their own reintegration. Many participated in combat from a very young age, and possess few skills beyond those learned in situations of violence. Peace can be very difficult for them to navigate. This needs to be recognised and incorporated into the thinking of the Colombian peace process as it develops under the new government.

On the last day of our visit to Agua Bonita, we asked Olmedo Vega what his biggest wish for the future is. “From the bottom of our hearts,” he said, “it is not to leave us alone. We have suffered war, and [since then] we have grown in hope and love. We carry on our backs the historical responsibility of generating reconciliation. We are dreaming of peace.”

*Some interviewees asked only to be identified by their first names