FREE FLOW OF INFORMATION .

An article from the Global Campaign for Peace Education (translated by The Global Campaign for Peace Education from the original French version by Anne-Marie El-HAGE in L’Orient Le Jour , May 8, 2023)

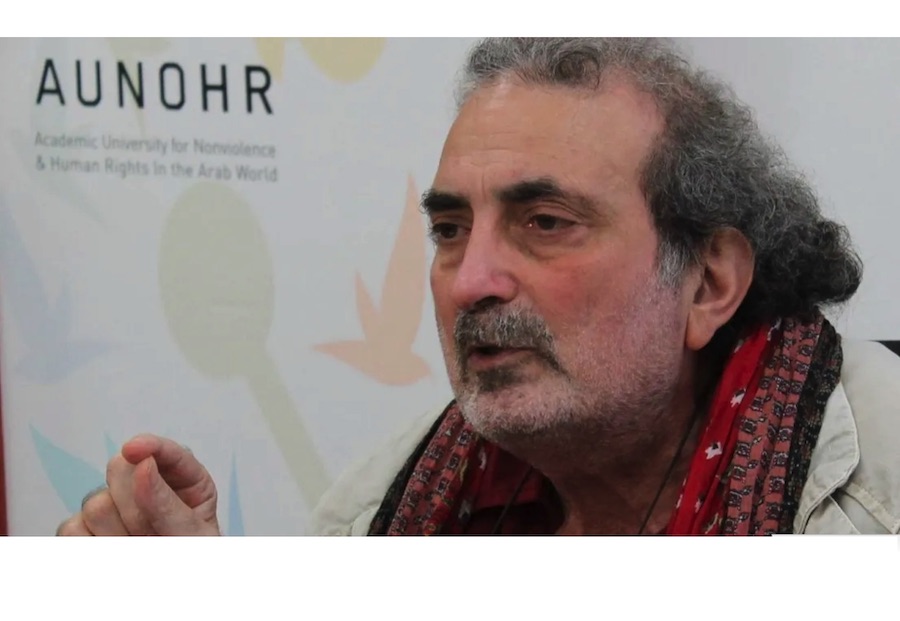

He was one of those followers of non-violence who made Lebanese society and the Arab world better. A thought that he developed during the civil war, in the same way as secularism, in reaction to the destructive consequences of the Lebanese intercommunity conflict on the social fabric. Walid Slaïby is no more. He died on Wednesday, May 3 at the age of 68, overcome by a cancer that had been eating away at him for more than 20 years. His name, inseparable from that of his companion in life and struggle, the sociologist Ogarit Younan, will forever be linked to activism for the right to life within the framework of the fight for the abolition of the death penalty. Civil rights will also be at the heart of his fight for a Lebanese personal status law. Along with workers’ rights and social justice, from the early 1980s.

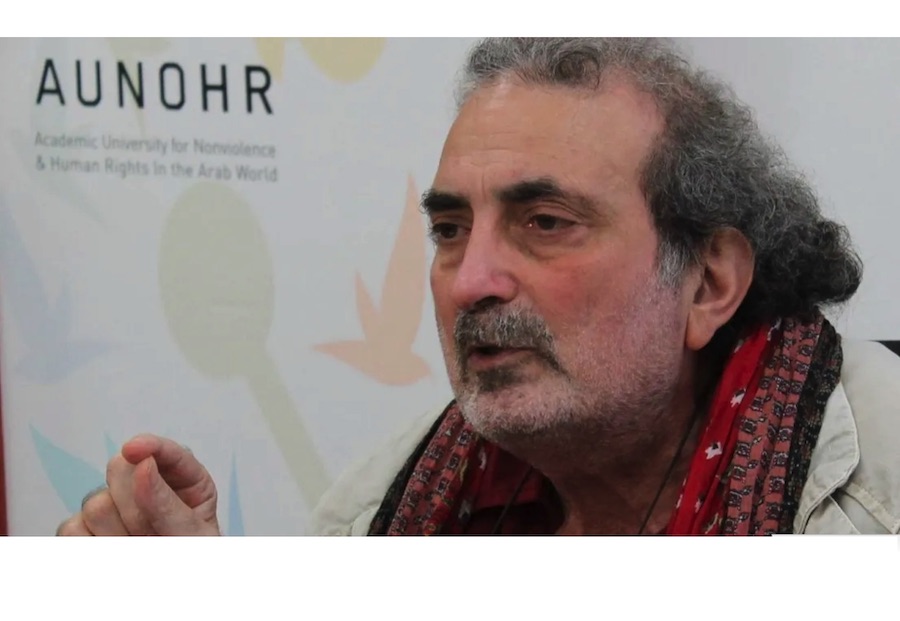

Walid Slaïby, follower of non-violence and death penalty abolitionist, died on May 3 at the age of 68. (Photo courtesy of Aunohr Media Services)

(Click on photo to enlarge)

An immense legacy

From his commitment to the service of Lebanon, he will leave an immense legacy. A multitude of books, publications, translations, bills, associations, tangible progress on the ground, always with Ogarit Younan. With the crowning achievement in 2015 of the Academic University College for Non-Violence & Human Rights (Aunohr), an educational institution dedicated to non-violence that continues to train generations of students, activists, trade unionists ready to take over. This course will see the duo rewarded several times, in particular by the Human Rights Prize of the French Republic in 2005, the Fondation Chirac Prize in 2019 and the Gandhi Prize for Peace awarded in 2022 by the Indian foundation Jamnalal Bajaj, named after the disciple of Mahatma Gandhi.

It is in his fight against the death penalty that Walid Slaïby initiated the most tangible progress. “He was a silent soldier against capital punishment. But his work was very important,” says Wadih Asmar, president of the Lebanese Center for Human Rights (CLDH). After federating several associations around the National Campaign for the Abolition of the Death Penalty, the activist rallied part of the political and judicial class to the cause, during shock events that were highly publicized. In 1998, when two burglars, one of whom had committed a double murder, were hanged in Tabarja in the public square, he openly proclaimed during a nocturnal sit-in “mourning for the victims of the crime and for those of capital punishment “. As a result, the last executions date back to 2004 in Lebanon, even if justice continues to pronounce the death sentence. “Lebanon is now classified as a de facto abolitionist country. In 2020, for the first time in its history, it spoke out for a moratorium at the UN General Assembly, alongside 122 other states. A position recently reiterated”, welcomes former minister Ibrahim Najjar, a committed abolitionist. The lawyer did not personally know the deceased, but he said he was “respectful and admiring of the courage of Walid Slaïby and his companion Ogarit Younan, who behaved as convinced abolitionists”. “Because the fight is not easy. It is so easy to confuse revenge with capital punishment,” he points out. for the first time in its history, it came out in favor of a moratorium at the UN General Assembly, alongside 122 other states.

(Article continued in the column on the right)

(Click here for the original version in French)

Questions related to this article:

Where in the world can we find good leadership today?

How can we carry forward the work of the great peace and justice activists who went before us?

(Article continued from the column on the left)

A position recently reiterated”, welcomes former minister Ibrahim Najjar, a committed abolitionist. The lawyer did not personally know the deceased, but he said he was “respectful and admiring of the courage of Walid Slaïby and his companion Ogarit Younan, who behaved as convinced abolitionists”. “Because the fight is not easy. It is so easy to confuse revenge with capital punishment,” he points out. for the first time in its history, it came out in favor of a moratorium at the UN General Assembly, alongside 122 other states. A position recently reiterated”, welcomes former minister Ibrahim Najjar, a committed abolitionist. The lawyer did not personally know the deceased, but he said he was “respectful and admiring of the courage of Walid Slaïby and his companion Ogarit Younan, who behaved as convinced abolitionists”. “Because the fight is not easy. It is so easy to confuse revenge with capital punishment,” he points out. but he says he is “respectful and admiring of the courage of Walid Slaïby and his companion Ogarit Younan, who behaved as convinced abolitionists”. “Because the fight is not easy. It is so easy to confuse revenge with capital punishment,” he points out. but he says he is “respectful and admiring of the courage of Walid Slaïby and his companion Ogarit Younan, who behaved as convinced abolitionists”. “Because the fight is not easy. It is so easy to confuse revenge with capital punishment,” he points out.

For a Lebanese Personal Status Law

The personality of Walid Slaïby is no stranger to his great popularity. “Walid was a man of dialogue, attentive to his friends. It is through debate and acceptance of the other that he succeeded in laying the foundations of the culture of human rights in Lebanon, and in particular of non-violence”, affirms Ziad Abdel Samad, friend of the couple, engineer and teacher in political science. “Despite the divisions of Lebanese society, he managed to go beyond the militias and the borders to lead an avant-garde struggle and achieve remarkable progress”, he observes, referring to the efforts of the deceased to raise awareness among young people and bring closer Lebanese of different faiths and backgrounds. It is also in the institutionalization of the fight that Walid Slaïby drew his strength. “When I met him in the early nineties, he organized human rights training against religious discrimination, remembers activist Rima Ibrahim. Despite his illness, he never stopped dreaming of changing Lebanese society, to the point of institutionalizing the fight.

Several associations were then created, linked to the Lebanese Association for Civil Rights (LACR), notably Chamel and Bilad. In 2011, the militant couple launched their campaign to demand a Lebanese law on personal status which advocates, among other things, civil marriage. In Lebanon, family laws are governed by religious communities. They discourage inter-religious unions and discriminate against women. “For the occasion, we organized a sit-in and set up a tent for 10 months, place Riad el-Solh, in downtown Beirut. We have also prepared a bill,” recalls Rafic Zakharia, lawyer, teacher and member of the association. Signed by MP Marwan Farès, the text is presented to Parliament and transferred to the joint commissions. “The law has not been adopted. But our mobilization has never weakened”, assures the activist, whose “life has changed” since he met Walid Slaïby. “Non-violent thinking has become a way of life for me, not just a fight,” observes this death penalty specialist.

The happiness of having given hope to the Lebanese

The militant, the thinker, the humanist endowed with superior intelligence and a good dose of humor left with modesty and elegance, as he has always lived. “Walid Slaïby was both a great humanist and a man of science. Very solid in his convictions, he was flexible when it came to discussing. Never giving lessons, he was not a man to show off, but on the contrary was very discreet, ”describes the lawyer and former minister Ziyad Baroud, member of the board of directors of Aunhor, who knows him. for over 25 years. Multi-graduate, the disappeared was indeed a civil engineer (ESIB), a graduate in physics (UL) and in economics (AUB). Studies he completed with a DEA in social sciences (UL),

He will be missed by human rights defenders, starting with abolitionists around the world who pay tribute to him and his companion. “It was a star of light and reason in a world of shadow and madness”, sums up Raphaël Chenuil-Hazan, director general of the international association ECPM (Together against the death penalty). “With Ogarit, they formed this incredible duo who have devoted their lives for more than 40 years for a modern Lebanon”, he continues, congratulating himself on having had “the chance to send him love before his death of the abolitionist community around the world. Walid Slaïby will especially be missed by his alter ego, his soul mate, Ogarit Younan, with whom he was to celebrate 40 years of love and activism. “We were expecting the weather to improve a bit. We wanted a nice party. We didn’t think he was so close to death. He loved life so much. He had so much humor,” she regrets sadly. And if the disease occupied a good half of their life together, he will at least have had “the happiness of serving his country and giving hope to the Lebanese”. “Lebanon must be happy, we have served it, consoles Ogarit Younan. But if Walid had not fallen ill, without a doubt, Lebanon would have been different…”