FREE FLOW OF INFORMATION

A blog from Glenn Greenwald

On Mother’s Day in 2019, I obtained a massive archive of materials from Brazil’s most powerful officials. The reporting we did changed the country, and our lives.

In 2015, I travelled to Sweden for an event with former Washington Post reporter Carl Bernstein. It was billed as a conversation about modern journalism between the reporter who had broken the biggest story of the prior generation (Watergate) and the one responsible for the biggest story of the current one (NSA/Snowden revelations).

A couple of years earlier, at the height of the Snowden reporting, Bernstein and I had traded some barbed insults through the media. So before traveling to Sweden, he generously reached out to invite me to dinner in order, essentially, to clear the air so that we could have a civil conversation. The night before the event, we met for dinner at the hotel restaurant. We quickly laughed off the acrimony — it had been a couple of years prior, and both of us have had much worse said about us — and proceeded to have a perfectly enjoyable conversation.

Truth be told, I was excited to meet and talk to Bernstein. Though his Trump-era persona became conventionally fixated on melodramatizing Trump’s evils for CNN, at the time Bernstein for me was most associated with the high investigative drama of Watergate. As a kid, it was that journalistic triumph, along with the Pentagon Papers, that captured my obsessive attention and shaped my views of what journalism is: reporters and whistleblowers who risk everything and face various multi-level dangers to confront and expose corruption by the most powerful actors in society. Throughout pre-adolescence, I spent countless hours reading All the President’s Men and repeatedly watching the excellent 1976 film based on it — in which Bernstein was played by Dustin Hoffman and Bob Woodward played by Robert Redford — and that noble and exciting iconography stayed with me and shaped how I view what journalism should be. It still does.

Our two-hour conversation that night covered many topics, but one comment from Bernstein stayed with me. “I know you likely already know this,” he said, “but a story like the NSA reporting you’re doing is a once-in-a-lifetime experience, so make sure to enjoy it while it lasts.”

But just a few years later in 2019, on Mother’s Day in Brazil, a series of events began that proved his prediction quite wrong. In the late morning, I received a call from Manuela D’Avila, a well-known two-term Congresswoman who was the Vice Presidential candidate on the center-left ticket that lost to Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil’s 2018 presidential election. She told me that, just hours before, her phone had been hacked, and the hacker showed her conversations he had obtained from her phone between her and several of her closest friends and colleagues that she had conducted on the Telegram app. She assumed she was the target of some kind of malicious blackmail scheme.

But the hacker quickly assured her that she was not his target. He had hacked her phone only to demonstrate that he had the capability of invading anyone’s Telegram account that he wanted. He told her that he had spent months hacking into the phones of some of Brazil’s most powerful officials, and had downloaded enormous amounts of material proving grave corruption on their part. They discussed how this material should be handled, and agreed that they would contact me — given my prior experience in reporting on a similar archive about NSA spying on Americans — to see if I was willing to work with this material. I told Manuela that of course I would be, and within minutes on that Sunday afternoon, I was talking on Telegram to the source.

What he told me was stunning, and it of course viscerally reminded me of the first time I was contacted back in 2012 by Edward Snowden. He said that he had obtained a gigantic digital archive of chats, documents, audios, videos, and photos from the telephones of Brazil’s most influential figures. He told me that he had reviewed less than ten percent of these materials, but already found acts of such grave deceit and illegality that he was certain it would shake Brazilian politics at its core.

The moments when you are first contacted by a source like this are delicate but critical. It is a difficult dance with conflicting goals. We spent roughly an hour talking as I tried to create a climate of trust, determine the authenticity of his claims, ensure that he was not an agent of entrapment, interrogate him without making it seem as if I were investigating or doubting him, and develop an understanding of what he did and why. Once satisfied that he was likely a genuine source, I told him he could start uploading the documents to my Telegram account.

For the next twelve hours, one document after the next materialized on my phone, a new one appearing every two or three seconds. I went to bed that night, woke up the next morning, and saw that the documents were still coming fast and furious. The same thing happened the next day, and then the day after, and then the day after that. It continued for a full week with no end in sight, at which point I realized that this archive would be larger than even the Snowden archive, which, in terms of sheer size, had been the largest leak in the history of modern journalism. This archive was larger, and so we had to work with technologists we trusted to build a dropbox that would provide a secure way for all the documents to be uploaded at once.

It took roughly three weeks to secure all the documents. I was particularly eager to ensure they were secured outside of Brazil, out of the reach of Brazilian courts and other state authorities. As they were uploading to my phone that first day, I worked with my Brazilian journalism colleague Victor Pougy to try to review as many of the documents as we could. Even using the crude method of randomly selecting documents to read, it became very evident that this archive was not only genuine but explosive — and aimed directly at the most powerful and popular political officials in the country.

The first conversation I had after speaking with the source was with my husband, David Miranda. He had played a central role in the Snowden reporting, having been notoriously detained by British authorities in 2013 at Heathrow Airport under a terrorism law while transporting a portion of the NSA archive we received from Snowden that had been corrupted. David’s detention occurred just weeks after British agents physically invaded the London newsroom of The Guardian and forced editors, under threat of an injunction, to physically destroy the computers on which their copies of the Snowden archive was maintained (that full copies of the archive were secure in other places, including with me in Brazil, did not deter their thuggish but futile actions).

David had traveled to Berlin because my brilliant colleague Laura Poitras — who directed the Oscar-winning film about our work with Snowden, CitizenFour — had managed to repair that part of the corrupted archive. David traveled to Germany to pick it up and bring it back to Rio for me to work on. His detention in London and the threats of prosecution he endured — approved of in advance by the Obama administration — not only caused a major rift in diplomatic relations between Brazil and the UK, but also became the subject of a successful lawsuit David brought against the British government, resulting in an enduring judicial ruling that the use of this terrorism law against journalists violated core press freedoms.

At the time the Brazil source had contacted me, David was an elected member of the Brazilian Congress. Just as we did when I first received the NSA archive from Snowden, we discussed the likely risks and dangers of doing this reporting. I told him that our experience in having navigated all the various threats from the Snowden reporting would render us well-prepared to deal with the fallout from the reporting on this new archive. He quickly disputed that view, insisting that it was naive and that it ignored the long-standing, as well as the new, realities of Brazil. He pointed out that unlike in the Snowden reporting — where the governments we were angering were thousands of miles away — this time we would be doing reporting on the people governing the country in which we lived. That, along with the fact that the newly elected Bolsonaro was at the peak of his power, having just been elected in a sweeping victory months before, would make this journalism far riskier and more intense.

But David’s primary argument was based in the particular dangers posed by the person most incriminated by this archive. That was Sergio Moro, who had become the singular most popular figure in Brazil when, as a low-level judge in the mid-sized city of Curitiba, he presided over a sweeping anti-corruption probe that sent to prison some of Brazil’s most powerful politicians and business people. The judicial probe that Moro led starting in 2014 — dubbed “Operation Car Wash” (lava jato in Portuguese) — became the most powerful force in Brazil. He and the team of young prosecutors he led imposed lengthy prison sentences on a wide range of powerful figures seemingly without blinking.

Venerated by Brazil’s all-powerful, oligarchical Globo-led media, Moro and the Car Wash prosecutors became religious-type icons in Brazil. Murals of Moro appeared on the sides of buildings in numerous cities. Moro was frequently depicted as Superman at political protests; he was the only Brazilian named in 2016 to the TIME 100 list list of the world’s most influential people; and polls showed he was by far the most popular figure in the country. The army of popular support behind him rendered all institutions afraid of him, including the superior courts responsible for overturning his rulings that clearly violated defendants’ rights. Nobody was willing to risk the wrath of the public by positioning themselves against SuperMoro.

It is hard to overstate the power Moro wielded. His actions, as an unelected low-level judge, drove virtually every major political event in Brazil for close to five years. His legally dubious decision to order the tape recording of private conversations between then-President Dilma Rousseff and former President Lula da Silva, and his even more dubious actions in causing those tape recordings to leak to the press, was the key event that drove the 2016 impeachment of Dilma from the presidency. But by far his biggest prize was the 2017 conviction on corruption charges of Lula, the most iconic figure in Brazil who was term-limited out of the presidency in 2010 after serving two consecutive terms and who left office with an 87% approval rating. When the newly elected Obama met Lula at the 2009 G-20 summit, he exclaimed: “This is my man, right here . . . the most popular politician on earth.”

The corruption case against Lula was sketchy from the start. But Moro quickly declared him guilty on all counts, and sentenced him to close to a decade in prison. At the time, it was widely known that Lula intended to run again for the presidency in 2018, and all polls showed him well ahead of all competitors, including Bolsonaro.

But an appeals court notorious for subservience to Moro quickly affirmed Moro’s guilty verdict, rendering Lula barred from running for office. In sum, Moro cleared the path for Bolsonaro by removing what was by far his biggest obstacle: Lula. As a result, Bolsonaro faced not the iconic and charismatic Lula, but instead the competent though little-known one-term Mayor of São Paulo, Fernando Haddad, who Lula, from prison, handpicked to run on his party line, and the right-wing Congressman easily cruised to victory.

One of Bolsonaro’s first acts upon winning was to reward the judge who had removed his most formidable opponent. He offered Judge Moro the most powerful position in his government: Justice Minister. But at the time, Moro was more popular than Bolsonaro, and Bolsonaro needed him more than Moro needed Bolsonaro. So Moro conditioned his joining the government on Bolsonaro’s willingness to consolidate massive powers of investigation, surveillance, detention and law enforcement — that had long been dispersed among numerous agencies and ministries — under his singular control. Bolsonaro quickly agreed. Just days after Bolsonaro’s stunning victory, Moro’s newly unveiled position — Minister of Justice and Public Security — was so unprecedentedly powerful that the Brazilian press referred to him as “Super Minister.”

(continued in right column)

Question(s) related to this article:

Free flow of information, How is it important for a culture of peace?

The courage of Mordecai Vanunu and other whistle-blowers, How can we emulate it in our lives?

(continued from left column)

So that was to be the principal target of our reporting: the most popular figure in Brazil, the anchor of the new Bolsonaro government, a judge whose tentacles extended into every sector of the Brazilian judiciary, and the state official now in charge of all government weapons of surveillance, monitoring, the Federal Police, and all investigative bodies.

What made this archive so explosive in every sense of the word was not just that its principal target was Moro, but far more importantly, the revelations of grave corruption it demonstrated. Among the documents were years worth of private chats between Moro and the lead Car Wash prosecutors, secretly and illegally plotting how to ensure convictions of the very defendants which Moro — as their judge — was duty-bound to arbitrate objectively and neutrally. These documents proved he was anything but neutral: he acted for years as the chief prosecutor, going so far as to direct and craft the law enforcement operations and the charges brought against criminal defendants, only to then walk into court, donning his black robe, and sending those same defendants to prison for many years with self-righteous sermons about the primacy of ethics and integrity in public service.

Most incriminating of all were the documents proving that Lula’s conviction was obtained through systemic, sustained corruption on the part of Moro and the team of prosecutors he led. The chats showed that the prosecutors knew that they lacked evidence of Lula’s guilt. The archive revealed how they plotted to illegally keep the case with Moro to ensure a guilty verdict. They showed Moro ordering the prosecutors to change strategies and even their public messaging against Lula as he was judging the case. They proved that Moro violated not only his own practices but also the law in first recording and then leaking to the press Lula’s private conversations, all to stoke public anger against Lula and engender support for his imprisonment. And they contained numerous admissions of political motives which the judge and prosecutors had long vehemently denied: that they were devoted to abusing their powers to prevent the return of Lula’s Workers’ Party to the presidency. And that was just a small sample of the grave corruption these materials demonstrated.

Brazil’s Constitution — enacted in 1988 upon re-democratization, after the 1964 U.S.-engineered military coup led to a 21-year brutal military dictatorship — provides press freedom guarantees more robust than the U.S. Constitution. But nobody knew if those words would matter. Bolsonaro — who had spent almost three decades in Congress arguing that military dictatorship is a superior form of government to democracy, and having vowed to close Congress and reinstate the most repressive dictatorship-era decrees if elected President — had just been inaugurated four months before I began speaking with this source. His party, which barely existed before 2018, became the second-largest in Congress. He was at the peak of his power. As we began the reporting, nobody knew whether Brazilian democratic institutions — young and fragile — had either the will or the power to uphold them.

Hovering over all of this was the brutal assassination just a year earlier of one of our closest friends, Marielle Franco, a black LGBT woman from the favelas elected along with David to the Rio de Janeiro City Council in 2016, only to be murdered in 2018. Although some do, I do not believe the Bolsonaros were directly involved in her assassination, but the paramilitary militia composed of current and retired agents of the police and military responsible for her assassination are closely linked to Bolsonaro’s family. Political violence has long been a central attribute of Brazilian politics, and it seemed certain that the empowerment of Bolsonaro’s movement would exacerbate that danger as well. Bolsonaro has often vowed as much, saying, for instance, that the primary error the military dictatorship was that it had not killed enough dissidents.

After spending weeks working on the archive with the team of young Brazilian journalists at The Intercept Brasil, the small news outlet I founded in 2016, we published our first series of reports from the archive on June 9, along with an Editors’ Note explaining what we had, why we were reporting it, and what methods we would use to determine what materials would be made public. We published them in both Portuguese and English. We purposely chose to simultaneously publish three of the most explosive stories at once, in large part due to the fear that Moro would be able to use his power to obtain a judicial order to restrain further publishing.

The impact was far greater than what we had even dreamed. The stories ricocheted throughout social media and then through the national press. They were by far the most-read stories in The Intercept‘s history. The reporting dominated headlines for weeks. Both Moro and I were summoned to the lower House and Senate, where we each testified for more than nine hours. I used strategies copied from our tactics in the Snowden reporting, which I believe gave us a significant strategic advantage: for weeks, the Bolsonaro government and Moro struggled to find their footing against the onslaught of revelations we were publishing, one after the next, eventually in partnership with Brazil’s largest news outlets.

But once they steadied themselves, the backlash was intense, beyond anything I had experienced. The next year of our lives — not just mine but David’s and the team of young journalists with whom we worked — was far more intense and difficult than anything we faced in the Snowden story. On a virtually daily basis, the top trending Twitter hashtags were ones calling for my immediate arrest or deportation. News reports were leaking that generals were discussing how to prosecute me under dictatorship-era national security laws. We received so many credible death threats — with private information about our home and our children — that we could not leave the house without armored vehicles and teams of armed security, an arrangement that continues through today. Protests around the country contained signs demanding my arrest. Documents forged by the Bolsonaro movement and promoted by his Senator-son purported to show that I had paid Russian hackers in bitcoins to obtain the documents, and a major news magazine put this deranged conspiracy theory on its cover.

News reports emerged that agencies under Moro’s control initiated investigations into my finances, and then, when the Brazilian Supreme Court stopped those, into David’s. He issued a decree providing himself with the power of summary deportation, widely viewed as directed at me. Threats of violence aimed at public events where I was scheduled to speak were so serious that some were cancelled while others had to concoct extreme security measures (I once had to speak from an off-shore boat at a literary event, while pro-Bolsonaro protesters shot fireworks horizontally at us and the crowd). I was attacked, physically, live on air, by a pro-Bolsonaro journalist the day before Lula was freed.

Bolsonaro repeatedly threatened prison and maligned our family as fraudulent. And in early 2020, I was charged with multiple felony counts in connection with the reporting, charges dismissed on the ground that the Brazilian Supreme Court, reacting the prior year to Bolsonaro’s threats against me, had prohibited any retaliatory action against me (prosecutors appealed dismissal of those charges, and that appeal is still pending).

But the journalism we did — in partnership with several of Brazil’s largest outlets, led by the team of courageous Brazilian journalists assembled by Leandro Demori, the young and dynamic editor-in-chief we hired in 2017 — was, along with the Snowden reporting, the most gratifying I have ever done. Among other things, it led to Lula’s being freed from prison and then, just last month, the reversal of all of his criminal convictions by the Supreme Court on the ground that Judge Moro’s conduct was improper. That has resulted in a full restoration of Lula’s political rights, which means he is almost certain to run against Bolsonaro in 2022 — a contest the Brazilian people were denied in 2018 by virtue of grave judicial and prosecutorial corruption (Moro, in 2020, quit his position, accusing Bolsonaro of corruption, and he ironically became the prime enemy of Bolsonaro’s supporters, who now often use our reporting to point to Moro’s corruption).

Even more importantly, I believe that the defiant and aggressive way we reported these materials emboldened institutions to stand up to Moro and in defense of democratic values. An Associated Press article that reported on my testimony before Congress — at which I was threatened for hours with prison by pro-Moro-and-Bolsonaro lawmakers — called the reporting “the first major test of press freedom under Bolsonaro, who took office on Jan. 1 and has openly expressed nostalgia for Brazil’s 1964-1985 military dictatorship — a period when newspapers were censored and some journalists tortured.” The reaction of Congress, the Supreme Court and even the national press meant that test was passed: we established the right of citizens and journalists to be protected by the basic rights guaranteed in Brazil’s Constitutions. Amazing and inspiring rallies around the country — attended by students and older activists and artists who were persecuted by the military regime — were commonplace, alongside more hostile ones that threatened violence.

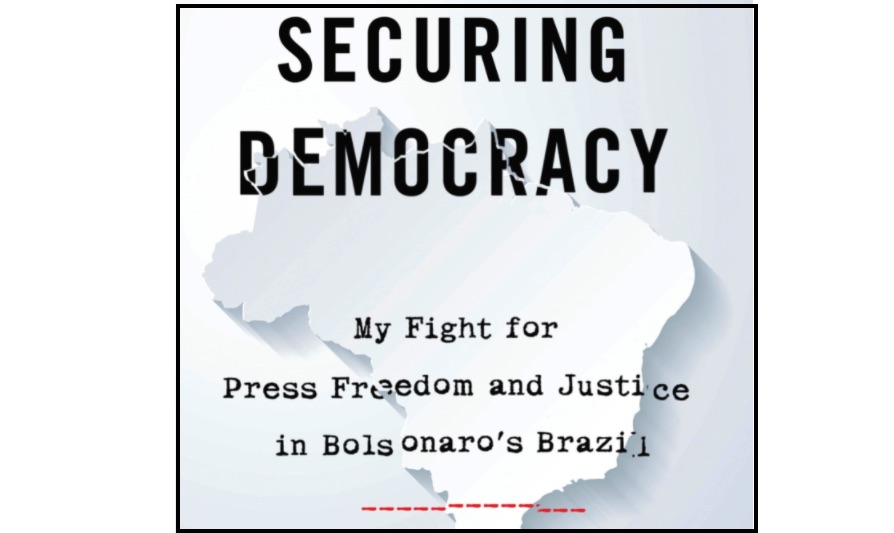

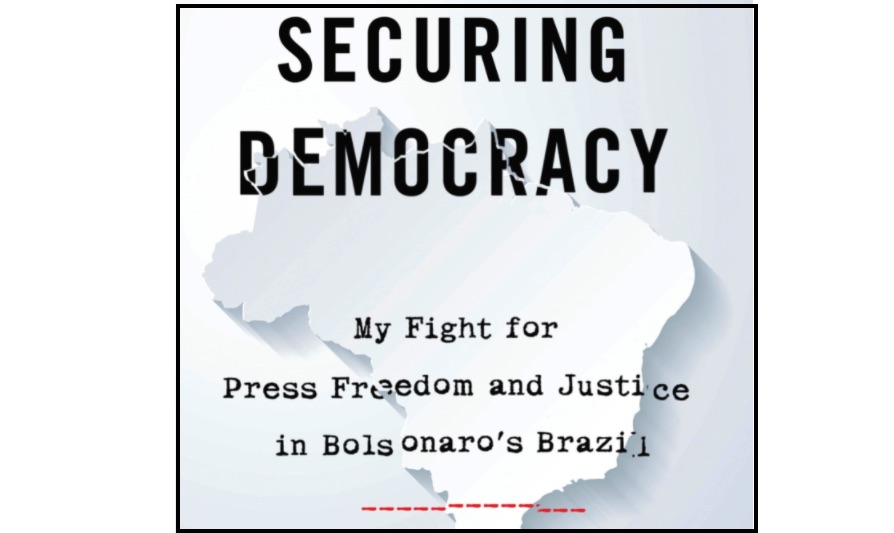

The book I have written about this entire series of events — entitled “Securing Democracy: My Fight for Press Freedom and Justice in Bolsonaro’s Brazil” — is being published today, in both hardcover and Kindle. You can order it here.

The book, of course, is partially about Brazil. The first chapter recounts the recent political and cultural history of this incredibly important and fascinating country, the path that led to Bolsonaro, and what lessons can be drawn for democracies around the world, including in the U.S. A representative excerpt from that first chapter — headlined “Why Brazil Still Matters”— was published on Monday by The Nation.

But I regard the book as being far more about journalism and democracy in general than about Brazil. Like my 2014 book No Place to Hide, which tells the story of what it was like to report on the NSA archive and work with Edward Snowden, a bulk of the book tells the story from the inside about what it was like to work with this source, how we did the reporting, the dangers and backlash we had to navigate, and the monumental changes it fostered for Brazilian politics. To me, though, the real theme is what journalism is supposed to be, why it is so vital to a healthy democracy when practiced in its highest form. People often question why I devote so much energy to criticisms of the U.S. corporate press, and this book demonstrates the reason: journalism when done right can produce enormous good, while corrupted journalism is toxic and poisonous for a democracy.

“Securing Democracy” has been very well-received by early reviews, including by Kirkus, by Jacobin, and by the Brazilian journalist Daniel Avelar. And the reporting we did and the resulting attacks and reforms were well-covered by the western press. But unlike the 2014 Snowden book — which was reviewed by most major print and television U.S. outlets — this book is likely to be ignored by them. In part it is because the key events take place in Brazil, but much more so it is because my status in the media ecosystem has changed dramatically since then. While I was never universally beloved by the U.S. corporate media, to put that mildly, my NSA work was with The Guardian and other major media outlets and that fact, along with the Pulitzer the reporting won, required them to pay attention. The war I have subsequently waged on how corporate journalism is practiced over the last few years incentivizes them to ignore the book.

But, to their great consternation, they no longer control discourse. There are numerous alternative outlets where one can now go to discuss one’s work. I have numerous independent outlets scheduled to discuss the book and have already begun some. But what Substack has enabled is that a writer can now have their own readership without being captive to the constraints of large corporate outlets, and that is what I am relying on: a direct relationship with my own readers.

I am at the place in my career where I would never write, let alone promote, a book that I did not believe in. I’m genuinely proud of the journalism I was able to do with my colleagues in this story, and I am equally proud of this book, which attempts not just to tell that dramatic story but highlight the core challenges, and unparalleled potential, of the role of real journalism in a democracy.

My book “Securing Democracy” is on Amazon in Kindle or hardcover or, if you prefer to support independent bookstores, on Bookshop as well. An audio version will be eventually available, but not likely until July.

(Thank you to the Transcend Media Service for calling this article to our attention.)