…. HUMAN RIGHTS ….

An article from UN Women (abridged)

During the 36-year-long Guatemalan civil war, indigenous women were systematically raped and enslaved by the military in a small community near the Sepur Zarco outpost. What happened to them then was not unique, but what happened next, changed history. From 2011 – 2016, 15 women survivors fought for justice at the highest court of Guatemala. The groundbreaking case resulted in the conviction of two former military officers of crimes against humanity and granted 18 reparation measures to the women survivors and their community.

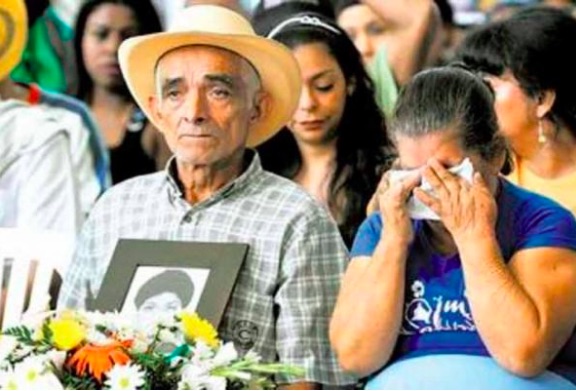

Maria Ba Call with members of her family. Photo: UN Women/Ryan Brown

The abuelas of Sepur Zarco, as the women are respectfully referred to, are now waiting to experience justice. Justice, for them, includes education for the children of their community, access to land, a health care clinic and such measures that will end the abject poverty their community has endured across generations. Justice must be lived.

The day the military came to take her husband and son is etched into Maria Ba Caal’s memory, but some of the details are fading. “When my husband and my 15-year old son were taken away, they were working men. The army came in the afternoon and took them away… I don’t remember the date, but that was the last time I saw my husband and son,” she said.

It’s been 36 years since that day. Maria Ba Caal is now 77 years old.

Like many other Maya Q’eqchi’ women of Sepur Zarco, a small rural community in the Polochic Valley of north-eastern Guatemala, Ba Caal is still looking for the remains of her husband and son who were forcibly disappeared and most likely killed by the Guatemalan army in the early 1980s.

The Guatemalan conflict

The Guatemalan internal armed conflict[1] dates back to 1954 when a military coup ousted the democratically elected President, Jacobo Arbenz. The subsequent military rulers reversed the land reforms that benefited the poor (mostly indigenous) farmers, triggering 36 years of armed conflict between the military and left-wing guerilla groups and cost more than 200,000 lives. Majority of those killed—83 per cent—were indigenous Maya people.[2] . . . .

In 1982[3], the military set up a rest outpost in Sepur Zarco. The Q’eqchi leaders of the area were seeking legal rights to their land at the time. The military retaliated with forced disappearance, torture and killing of indigenous men, and rape and slavery of the women.

“They burnt our house. We didn’t go to the Sepur military base (rest outpost) by choice…they forced us. They accused us of feeding the guerillas. But we didn’t know the guerillas. I had to leave my children under a tree to go and cook for the military… and…” Maria Ba Caal leaves that sentence unfinished. It hangs in the air as we sit in front of her mud shack. Her great grandchildren are playing nearby. She cries quietly.

Rape and sexual slavery are not words that translate easily into Q’eqchi. “We were forced to take turns,” she continues. “If we didn’t do what they told us to do, they said they would kill us.”

For years afterwards, Maria Ba Caal and other women who were enslaved by the military were shunned by their own communities and called prostitutes. Guatemala’s civil war was not only one of the deadliest in the region, it also left behind a legacy of violence against women.

The community of Sepur Zarco has about 226 families today. From the nearest town of Panzós, it’s a 42 Km drive down a dusty road that hasn’t been fully paved.

A few miles before Sepur Zarco stands the skeleton frameworks of a farm house in Tinajas Farm, surrounded by corn fields. In May 2012, the Fundación de Antropología Forense de Guatemala [the anthropological and forensic foundation of Guatemala] exhumed 51 bodies of indigenous peoples from this site, killed and buried in mass graves by the Guatemalan military. The evidence from Tinajas was one of the turning points in the Sepur Zarco case.

Paula Barrios, who heads Mujeres Transformando el Mundo (Women Transforming the World) explained that the indigenous communities living around the area believed that more than 200 men were brought here and never seen again.

“This was the truth of the Q’eqchi’ people, but we had to prove that the stories were true. The exhumation continued for 22 days and cost Q.100,000 (USD 13,500). Some families heard and came to the site, hoping to find their lost ones. Women from the Sepur Zarco community came and cooked for the crew. For four days they dug and dug but didn’t find any bodies. The anthropologists said that the next day would be the last day.”

“They found the first body the next day.”

(Article continued in the right column)

(Article continued from the left column)

In 2011, 15[4] women survivors of Sepur Zarco—now respectfully called the abuelas (grandmothers)—took their case to the highest court of Guatemala, with the support of local women’s rights organizations, UN Women and other UN partners.

After 22 hearings, on 2 March 2016, the court convicted two former military officers of crimes against humanity on counts of rape, murder and slavery, and granted 18 reparation measures to the women survivors and their communities. This was the first time in history that a national court prosecuted sexual slavery during conflict using national legislation and international criminal law.

The abuelas fought for justice and reparations not only for themselves, but for change that would benefit the entire community. The court sentence promised to reopen the files on land claims, set up a health centre, improve the infrastructure for the primary school and open a new secondary school, as well as offer scholarships for women and children—measures that can lift them out of the abject poverty they continue to endure.

“When we took our case to court, we believed we would win, because we told the truth,” said Maria Ba Caal. “To me it’s very important that our voice and our history is known to our country so that what we lived through never happens to anyone else.”

As part of the reparation measures, civil society organizations worked with the Guatemalan Ministry of Education to develop a comic book for children, which narrates the history of Sepur Zarco. The book will be distributed in secondary schools across Guatemala City, as well as in the municipalities of Alta Verapaz area.

Only one of the 11 surviving abuelas who fought for the groundbreaking case has a home in Sepur Zarco. Most of the others live in the surrounding communities of San Marcos, La Esperanza and Pombaac in make-shift homes. There’s a small plot of land behind the women’s centre that’s now under construction, which has been promised to the abuelas for building their homes.

Maria Ba Caal and Felisa Cuc gave us a tour of the area. Felisa Cuc is 81 years old, and is waiting for her home. She wants a house of brick and tin.

“When I heard the sentence, I was very happy. I thought my life will improve. But at this moment, I don’t know if I will live long enough to see the results.”

Doña Felisa has had a hard life. The soldiers took her husband away in 1982 and tortured him. He was never seen again. “I was raped, along with my two daughters who were young married women then. Their husbands had left… We tried to escape, we sought shelter in abandoned houses, but the soldiers found us. My daughters were raped in front of me.”

The Sepur Zarco military rest outpost closed by 1988 and the conflict formally ended in 1996 with the signing of the peace agreement. But the abuelas continued to scramble for a bit of dignity, a bit of land, and food.

Doña Felisa took us to her home in Pombaac, walking through dirt roads across corn fields. The last house in Pombaac is hers.

“There are so many needs,” she said. “At this moment, I need something to eat. No one knows how much longer I will live. I need land for my children. Perhaps if they have land to cultivate they can help me, feed me.”

Out of all the reparation measures, land restitution is perhaps one of the most critical ones, but difficult to implement since much of the land being claimed is held privately. The President has to appoint an institution and the Ministry of Finance has to provide a budget to the institution to buy the privately held land and then redistribute it.

One reparation measure that has had some traction is the free mobile health clinic, which serves 70 – 80 people every day. “We had to walk long to get to a clinic, but now it’s closer. Each community takes turn to take care of the clinic. Many women from my community have received medicines, but there are sicknesses that cannot be treated here…we dream of a hospital that can treat all our illnesses,” explained Rosario Xo, one of the abuelas.

Demesia Yat, an outspoken figure among the abuelas, recognizes how far they have come and also what’s at stake: “Our effort, first as women, and second as grandmothers, is very important. It’s true that we got justice. We are now asking for education for our children and grandchildren so that the youth in the community have opportunities and aren’t like their elders who could not study. Our claims are with the government. We waited for many years for justice, now we have to wait for reparations.”

The Sepur Zarco case is about justice, as shaped by women who endured untold horror and loss, and today they are demanding to experience that justice in their everyday lives.

Notes

[1] The conflict in Guatemala is officially referred as the “internal armed conflict”.

[2] The timeline has been corroborated with facts from the following sources: Memory of Silence: The Guatemalan Truth Commission Report; Case Study Series: Women in Peace and Transition Processes and Timeline: Guatemala’s Brutal Civil War by PBS News Hour

[3] For more facts and figures, see https://www.ghrc-usa.org/our-work/important-cases/sepur-zarco/

[4] The lawsuit was based on the violation of 15 women from Sepur Zarco, but the court could only verify the evidence of 11 of them as three of the victims died.