… . HUMAN RIGHTS … .

An article by Pascale Hunt in The Diplomat

Anti-racism protests across Australia amassed tens of thousands of supporters over the weekend. The murder of George Floyd, a black man, by a police officer in the United States on May 25 provided the catalyst for a global wave of solidarity with the black community to condemn police brutality and demand meaningful change. But neither Floyd’s murder, nor the anti-racism movement that it has sparked, should be considered surprising or spontaneous deviations from the circumstances found in local communities the world over. In Australia, the glaring issue of Aboriginal deaths in custody has become the obvious parallel drawn – 432 deaths since the Royal Commission in 1991, and not a single conviction. As in the United States, these crimes have occurred against the backdrop of centuries of structural and cultural violence.

.

A rally organizer leads a march from King George Square to South Brisbane at a Black Lives Matter protest on June 6, 2020, to support the movement over the death of George Floyd in the U.S. and the deaths of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islands people in custody in Australia. Credit: AP Photo/John Pye

The nature of the unequal interactions between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians within the structure of Australian society today prevents equality not only from being realized but from even being imagined. In understanding the dynamics of this reality, and if we hope to make progress toward equality and reconciliation, we should understand violence as tri-faceted in its manifestations, including not only direct (meaning physical) violence, but also structural and cultural aspects. Structural violence refers to violence that is embedded economically, socially, or legally, manifesting as unequal opportunities to realize quality of life, security, and self-actualization, whereas cultural violence is revealed in the social legitimization and justification of structural and direct violence.

The Indigenous peoples of Australia have suffered direct, structural, and cultural violence since colonization began over 200 years ago. While the exact numbers are contested, it has been estimated that there were between 300,000 and 1 million Indigenous peoples living on the Australian continent at that time, dispersed across over 200 nations – many of those lives were lost in direct combat and massacres at the time of British settlement. Today, the Indigenous peoples of Australia compose only 2 percent of the country’s population, making up a miniscule minority in their own lands – and life expectancy for Indigenous communities is some 25 percent below the rest of the Australian population. Australia has been accused of ethnic cleansing and of breaching the principles outlined in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples – according to the United Nations Convention on Genocide, Article II, assorted historical policies of child removal and forced assimilation are considered genocidal.

It was only as recently as 1967 that Indigenous Australians were recognized as citizens – and in almost all contemporary statistics, Indigenous people are in much worse circumstances than other groups in the country. One of the most shocking examples is that today, the average lifespan for Indigenous Australians is 20 years less than the non-Indigenous population, despite both groups residing in what has been called “the wealthiest country in the world.” Furthermore, it is worth noting that Indigenous identity itself never existed until the colonial event to juxtapose it – since then, Indigeneity has transformed from a colonial construct into a politicized identity, as Indigenous peoples continue to struggle for recognition of their basic rights.

It should be understood that continued suppression of Australian Indigenous peoples, appearing today in the form of structurally and culturally violent policies and attitudes, is required to maintain the security of the settler colonies’ original interest. The nature of the settler-colonial context is an example of cultural violence itself – the land was declared terra nullius, meaning “land belonging to no one,” from the outset, justifying the immediate atrocities committed as well as the subsequent dehumanizing structures that continue to characterize the settler-Indigenous relationship. The settler-colonial context in general – and the conflicts that arise from it – are distinctive in that their primary interest was, and is, in securing permanent control of the land through dispossessing native populations, achieved by suppressing the significance of Indigenous presence. In the Australian case, the significance of Indigenous people’s territorial dispossession is compounded by their deep cultural and spiritual interconnectedness with their ancestral land.

How Indigenous Australians have been affected by historically embedded structural violence is evident in that they are often required to hand over land rights in exchange for basic services that other Australians get without strings attached.

Indigenous rights that are protected in the Northern Territory Land Rights Act (1976) prevent the government and private companies from accessing rich uranium deposits – a concession that exemplifies a huge opportunity cost for the mining industry that is largely responsible for Australia’s national wealth. With this in mind, relatively recent events such as the Northern Territory intervention of 2007 – in which the government enacted a unilateral military occupation of NT communities’ land, quarantined 50 percent of Indigenous welfare payments, suspended the Racial Discrimination Act, and subjected Indigenous children to non-consensual health checks under the pretext of protecting them – can be interpreted as a strategic continuation of the original colonial-imperial agenda.

The mining industry is the biggest contributor to Australian GDP growth, and comes into direct conflict with Indigenous land rights, posing a significant struggle over the control of resources that support the maintenance of mining profits. Legislation such as the Aboriginal Land Rights Act (1976) in the Northern Territory has in some instances allowed the Indigenous community to influence development decisions – or at least share in the capital benefits – but in general, the legal, policy, and institutional environment remains hostile to Indigenous interests, heavily favoring those of mining corporations. Amendments to the Native Title Act made in 1998 imposed stricter requirements for registering Native Title claims, and simultaneously removed the “right to negotiate” from the renewal of mining leases. Not by coincidence, the NSW Office of the Environment and Heritage shows that between June 2012 and June 2013 there were over 99 applications for the destruction of Aboriginal heritage sites for development purposes – all of which were approved.

(Article continued in right column)

Are we making progress against racism?

(Article continued from left column)

Importantly, mineral development prevents and excludes Indigenous people from being on country, hunting and gathering, and carrying out rituals. Their capacity to negotiate with developers is severely undermined by government non-funding of Native Title Representative Bodies, which exist to support traditional owners in negotiations with commercial interests, leaving many Indigenous individuals and organizations with no choice but to rely on project developers for funding. This dynamic fundamentally alters the negotiating process. Ultimately, mining companies are driven by aspirations for capital accumulation that override their ostensible commitment to corporate social responsibility norms.

The media continues to facilitate the structural and cultural violence that permeates the relationship between settler and Indigenous Australians. Conventional reporting structures that rely on official sources and dualistic tug-of-war conceptions of conflict situations often ignore the root causes of conflict, the diversity and legitimacy of various stakeholders’ perspectives, and the complexity of myriad processes taking place. In the Australian media, Indigenous peoples are often portrayed as less successful in society, encouraging perceptions that this is the outcome innate group traits such as substance abuse or lack of initiative, rather than a consequence of broader structural factors and policies that prevent Indigenous peoples from realizing their goals. This effect is multiplied due to the comparative size of the Indigenous population to the rest of the country in Australia, as well as the intense concentration of media ownership in the country, which undeniably promotes elite and private interests. A feedback loop is created when culturally violent attitudes are distributed, justifying the structurally violent system, creating more circumstances that can be reported in a way that compound both. The inevitable outcome is a reinforcement of status-quo ideology, and a barrier preventing conflict comprehension and conflict resolution.

A primary obstacle to the reconciliation process in Australia is achieving acknowledgement among the wider public that the conflict is still happening. The official reconciliation process has been a mostly top-down approach, reflective of the colonial project from which the current system derives. It has failed to seriously address the injustices that have been done – primarily, the forced dispossession of land that lies at the heart of the conflict. It has been largely symbolic, emphasizing apology and forgiveness over structural and relational change – in other words, official reconciliation has failed to address the causal connection between structurally entrenched social disadvantage and the original dispossession of land that occurred. Nuanced contextualization that accounts for the historical abuses that have characterized the Indigenous-settler relationship is essential in order to understand the nature of the contemporary conflict and explore options for holistic reconciliation and conflict transformation.

Reconciliation itself has been criticized as a replacement for calls for sovereign recognition, and for characterizing historical events as “past injustices” that are unrelated to contemporary realities. While the process ostensibly aimed to address structural injustices affecting Indigenous communities, it failed to locate these structural injustices within the historical colonial context of land dispossession and the imposition of policies that continue to control Indigenous destinies. Former Prime Minister John Howard advocated a “practical reconciliation” agenda, in which policies would be implemented to target social inequalities in areas of employment, education, housing, and health – suggesting that reconciliation efforts should “focus on the future.” This discourse emphasized friendship and forgiveness – an idea that is beneficial to those seeking to reinforce a unified nation-state, but fails to recognize Indigenous calls for justice.

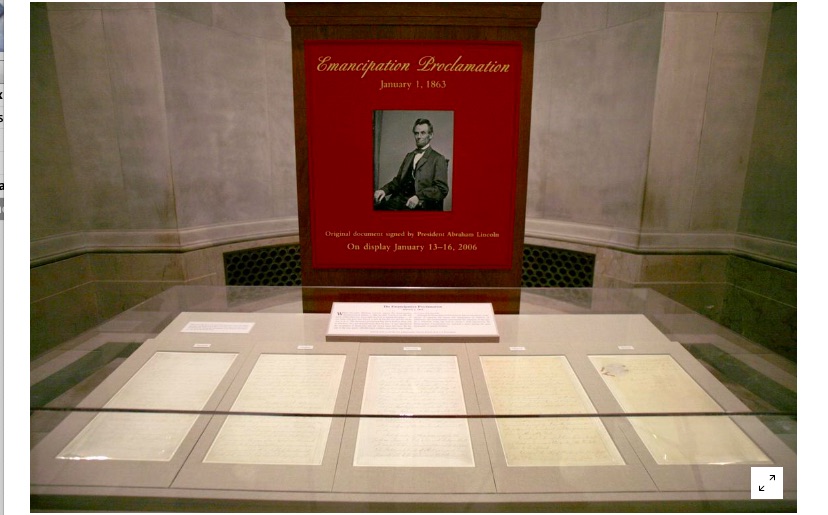

Since the 1960s, there have been several nonofficial political campaigns centered on the concept of land rights and self-determination of Indigenous Australians and challenging the established history of the settler society. One of the most iconic – inspired by the U.S. Civil Rights movement – was when a group of students took part in a peaceful protest known as the “Freedom Rides,” travelling around New South Wales fostering awareness about Indigenous sovereignty. These representations of the continent’s history spurred growing demands for recognition of Indigenous rights and sovereignty, directly challenging the state’s reputation as a liberal democracy, and called for the establishment of a treaty such as had been the practice in the United States, Canada, and New Zealand. In 1988, the largest-ever protest for Indigenous rights occurred in Sydney during the bicentennial celebrations and aimed to raise awareness about the original custodianship of the continent. While over 20,000 Indigenous Australians congregated in solidarity and protest of the previous 200 years of treatment, their presence was ignored by media reports – which instead chose to cover the many ships gathered in Sydney Harbor for the government-sponsored Australia Day celebrations.

In recent decades, there has been a noticeable increase in the symbolic use of Indigeneity as a part of the Australian nation-building project – discounting the truth of Indigenous Australians and appropriating the country’s controversial history by establishing a false connectedness between settlers and the land, thereby weakening Indigenous claims to sovereignty. Instead of addressing the unequal relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, the government promoted a nationalistic rhetoric that preached a “unified Australia” at the expense of Indigenous voices. It was a presentation that was beneficial to the state – facilitating the mythic character of the Australian nation as the “lucky country” in a way that dismissed the perspective of the Australian Indigenous population. In effect, it masked Indigenous dissent in a cover of self-congratulatory celebrations that were aimed at allowing settler Australians and the Australian state to stand proud with their identity, at the expense of the message that 20,000 Indigenous Australians that had gathered for. There is glaring opportunity for the media to play a more effective role in acknowledging history and facilitating discussion about the context underpinning the present situation.

In 2008, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd formally apologized to the stolen generations. The apology was greatly important for many Indigenous peoples and provided a sense of healing and symbolic justice. However, the over-emphasis on the apology in the media has allowed politicians to dodge meaningful reforms toward actual justice for Indigenous Australians. In February 2015, Rudd reflected on his apology, noting that as a country, “our achievements have been meager… the purpose of the apology was not to provide the nation a fleeting feel-good moment… it was to harness our collective energies for breaking the cycle of Indigenous disadvantage for the future.”

Permeating structural and cultural violence against Indigenous Australians has not been sufficiently addressed, and this hinders progress toward reconciliation and conflict resolution. The settler-colonial context, which manifests today in structurally violent attitudes and culturally violent policies with the media as a key player in maintaining the status quo, prioritizes national business interests that exacerbate the original injustice of Indigenous land dispossessions. A comprehensive understanding of the nature and context of the conflict, facilitated by dialogue and respect, is essential, along with an acknowledgement that the present situation is derived from the historical and contemporary denial of Indigenous rights, freedoms, and human needs.

It is understandable – given the history of structural, cultural and direct violence in Australia – that many Indigenous peoples feel that they will not have true justice until they are granted substantive land rights, sovereignty, and the ability to control their own destinies. While it may be too late in the game to turn over the extent of reparations that is deserved, the reconciliation process could undoubtedly involve more substantive, structural change that would make a real difference to the living conditions, dignity, and identities of Indigenous peoples, and contribute toward mending the broken relationship between settler Australians and the original custodians of this land.

Reuters Video of Washington demonstations

Reuters Video of Washington demonstations Another website with many photos of the demonstrations throughout the United States

Another website with many photos of the demonstrations throughout the United States