. . WOMEN’S EQUALITY . .

An article from Open Democracy

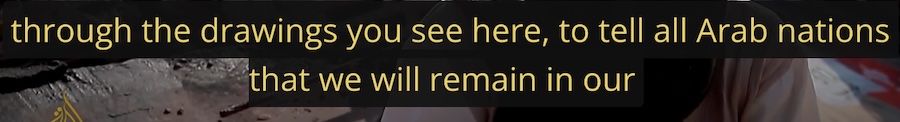

On 4 October, thousands of women met in Jerusalem at an event led by the Israel-based Women Wage Peace and the Palestine-based Women of the Sun to discuss how to bring peace to the region. Three days later, one of the former group’s founding members, Canadian-Israeli activist Vivian Silver, was killed by Hamas in the deadliest attack on Israel in its 75-year history.

The women’s work has become much more difficult in the weeks since. Some 1,200 Israelis were killed in the attack and 160 taken hostage, more than 100 of whom are yet to be released. Israel has responded by reducing much of northern Gaza to rubble, killing 15,000 Palestinians and wounding 30,000 more.

Peace now seems a distant prospect. But the women have not given up hope. In a statement released on 14 October, Women Wage Peace said: “Every mother, Jewish and Arab, gives birth to her children to see them grow and flourish and not to bury them.

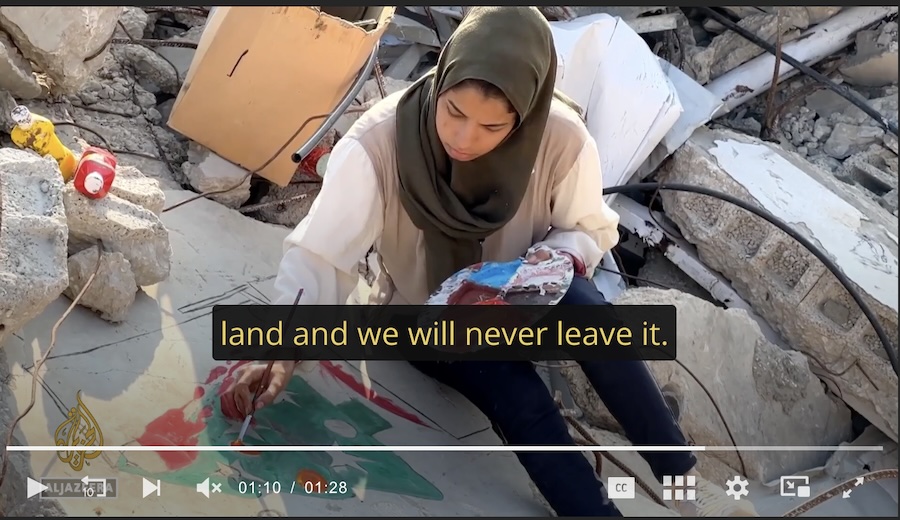

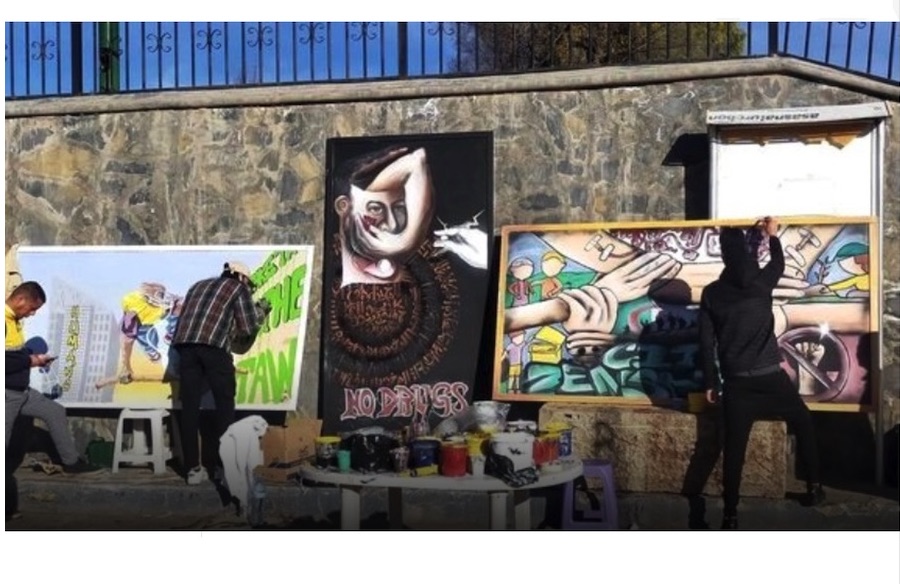

Branches of Women in Black lead silent vigils around the world to call for peace | Jesus Merida/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

“That’s why, even today, amid the pain and the feeling that the belief in peace has collapsed, we extend a hand in peace to the mothers of Gaza and the West Bank.”

As Siobhan Byrne of the University of Alberta later said: “This was undoubtedly a difficult statement to write through their grief and anguish.”

Both Women Wage Peace and Women of the Sun are relatively recent movements for peace in the Middle East but another women-led group has been calling for Israelis to end the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza for 35 years.

Women in Black (WiB), a low-profile, remarkably persistent and very global movement, was launched in West Jerusalem in January 1988, prompted by the first intifada the previous year.

The group is distinctive in two main ways: firstly for the role of vigil in its fight for change and secondly, for its varying calls of witness, not just in war but more generally on violence against women.

Its protests often take the form of public vigils by small groups of women, dressed entirely in black, largely silent and bearing messages of their beliefs. The vigils are repeated, often on specific days of the week and in the same place, such as outside a mall or in a city square.

As for its calls of witness, they may vary with country or local circumstance, but they may have a common message of the need for peace, either in a specific conflict or on a generic issue, though they also extend to much more pervasive issues of gendered violence, both in time of war and in wider society.

Feminist activist and scholar Cynthia Cockburn, who was among the most persistent supporters of WiB, began to write a book on the history of the movement in February 2019. Though she sadly died later that year having written only the first five chapters, the book was completed, at her request, by Sue Finch, aided by copious files that Cockburn had left and by people in WiB groups from across the world.

(Article continued in right column)

Do women have a special role to play in the peace movement?

How can a culture of peace be established in the Middle East?

(Article continued from left column)

Published earlier this year, Women in Black: Against Violence, for Peace with Justice tracks the development of the movement over more than three decades. It details how WiB is not a centrally organised entity but more a coalition of groups that snowballed across the world within six months of the movement’s start in Jerusalem.

Italian feminist activists, who had travelled to Israel and Palestine as part of a project called ‘Visiting Difficult Places’ in the late 1980s, joined WiB’s actions and took their approach back home. A feminist community in Belgrade, in what was then Federal Yugoslavia, in turn learned from them, and a similar approach evolved there. That group remained active throughout the breakup of Yugoslavia in the 1990s, bearing witness against the Bosnian and Kosovo wars.

Over time, WiB spread to Colombia, Germany, India, South Africa, Argentina and more than a dozen other countries spanning five continents, and nine international WiB conferences took place.

Introducing the book, Cynthia Cockburn summed up the movement’s evolution over the years, describing the differences between the various groups that had sprung up. “For some, especially those living through war,” she wrote, “theories about the relationship between gender and militarism are the most vital.

“Other women, living in relative peacetime choose combating male violence against individual women, and campaigning for the right to abortion, contraception and control over their own bodies, as the centre of their activism.

“The theories that connect Women in Black across the world, as a result, include the continuum of violence against women, and a causal relationship between gender and war.”

Women in Black is not a rigid centrally organised movement but has considerable autonomy between countries and branches. Any group of women in any part of the world may organise a vigil and while that is the most common action, responses may also involve nonviolent direct action at military bases or simply refusing to comply with orders.

A uniting feature is the value of the sense of solidarity, with women in one branch in a particular country knowing that if they bear witness to a particular happening or circumstance such as a specific conflict or incident of repression, they will be acting alongside a group in the country and also o9thersw across the world.

Because of its structure, the numbers involved in WiB may vary. Writing on its website, the movement gives one example: “When Women in Black in Israel/Palestine, as part of a coalition of Women for a Just Peace, called for vigils in June 2001 against the Occupation of Palestinian lands, at least 150 WiB groups across the world responded… The organisers estimate that altogether 10,000 women may have been involved.”

In recent years, Cockburn’s own writings, including on global disarmament and women peacemakers, have been highly influential. She worked in many regions of tension and conflict – including Northern Ireland, the Balkans, Israel/Palestine, Cyprus, South Korea, Spain and the UK – on a wide range of projects primarily focused on gender, war and peace-making.

Her work was paralleled by many years of activism, much of it stemming from an early visit to the Greenham Common women’s peace camp in 1980, and in 1993 she was heavily involved in establishing Women in Black in London. This book is certainly a very valuable contribution as a hugely informative account of the growth of what is now a worldwide movement but it is also a fitting remembrance of Cynthia Cockburn, a remarkable person.

– – – – – –

If you wish to make a comment on this article, you may write to coordinator@cpnn-world.org with the title “Comment on (name of article)” and we will put your comment on line. Because of the flood of spam, we have discontinued the direct application of comments.