The following excerpts come from an analysis made by Richard Falk, former UN Rapporteur for Palestine. They were published 14 years ago in response to Israeli attacks on Palestine, but they are still pertinent today in 2023 in response to the attacks of Israel on Gaza:

International Criminal Court

The most obvious path to address the broader questions of criminal accountability would be to invoke the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court established in 2002. Although the prosecutor has been asked to investigate the possibility of such a proceeding, it is highly unlikely to lead anywhere since Israel is not a member and, by most assessments, Palestine is not yet a state or party to the statute of the ICC. Belatedly, and somewhat surprisingly, the Palestinian Authority sought, after the 19 January ceasefire, to adhere to the Rome Treaty establishing the ICC. But even if its membership is accepted, which is unlikely, the date of adherence would probably rule out legal action based on prior events such as the Gaza military operation. And it is certain that Israel would not cooperate with the ICC with respect to evidence, witnesses or defendants, and this would make it very difficult to proceed even if the other hurdles could be overcome.

(Note: According to an update by Reuters , the ICC has had an ongoing investigation in the occupied Palestinian territories into possible war crimes and crimes against humanity there since 2021. But Israel doesn’t recognise the court. Many of the world’s major powers are not members, including China, the United States, Russia, India and Egypt. Even if the ICC were to issue warrants in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the court has no police force and would rely on member states to make arrests.)

International criminal tribunals

The next most obvious possibility would be to follow the path chosen in the 1990s by the UN Security Council, establishing ad hoc international criminal tribunals, as was done to address the crimes associated with the break-up of former Yugoslavia and with the Rwanda massacres of 1994. This path seems blocked in relation to Israel as the US, and likely other European permanent members, would veto any such proposal. In theory, the General Assembly could exercise parallel authority, as human rights are within its purview and it is authorised by Article 22 of the UN charter to “establish such subsidiary organs as it deems necessary for the performance of its function”. In 1950 it acted on this basis to establish the UN Administrative Tribunal, mandated to resolve employment disputes with UN staff members.

The geopolitical realities that exist within the UN make this an unlikely course of action (although it is under investigation). At present there does not seem to be sufficient inter-governmental political will to embark on such a controversial path, but civil society pressure may yet make this a plausible option, especially if Israel persists in maintaining its criminally unlawful blockade of Gaza, resisting widespread calls, including by President Obama, to open the crossings from Israel. Even in the unlikely event that it is established, such a tribunal could not function effectively without a high degree of cooperation with the government of the country whose leaders and soldiers are being accused. Unlike former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, Israel’s political leadership would certainly do its best to obstruct the activities of any international body charged with prosecuting Israeli war crimes.

Claims of universal jurisdiction

Perhaps the most plausible governmental path would be reliance on claims of universal jurisdiction (1) associated with the authority of national courts to prosecute certain categories of war crimes, depending on national legislation. Such legislation exists in varying forms in more than 12 countries, including Spain, Belgium, France, Germany, Britain and the US. Spain has already indicted several leading Israeli military officers, although there is political pressure on the Spanish government to alter its criminal law to disallow such an undertaking in the absence of those accused.

This path to criminal accountability was taken in 1998 when a Spanish high court indicted the former Chilean dictator, Augusto Pinochet, and he was later detained in Britain where the legal duty to extradite was finally upheld on rather narrow grounds by a majority of the Law Lords, the highest court in the country. Pinochet was not extradited however, but returned to Chile on grounds of unfitness to stand trial, and died in Chile while criminal proceedings against him were under way.

Whether universal jurisdiction provides a practical means of responding to the war crimes charges arising out of the Gaza experience is doubtful. National procedures are likely to be swayed by political pressures, as were German courts, which a year ago declined to proceed against Donald Rumsfeld on torture charges despite a strong evidentiary basis and the near certainty that he would not be prosecuted in the US, which as his home state had the legally acknowledged prior jurisdictional claim. Also, universal jurisdictional proceedings are quite random, depending on either the cooperation of other governments by way of extradition or the happenchance of finding a potential defendant within the territory of the prosecuting state.

It is possible that a high profile proceeding could occur, and this would give great attention to the war crimes issue, and so universal jurisdiction is probably the most promising approach to Israeli accountability despite formidable obstacles. Even if no conviction results (and none exists for comparable allegations), the mere threat of detention and possible prosecution is likely to inhibit the travel plans of individuals likely to be detained on war crime charges; and has some political relevance with respect to the international reputation of a government.

There is, of course, the theoretical possibility that prosecutions, at least for battlefield practices such as shooting surrendering civilians, would be undertaken in Israeli criminal courts. Respected Israeli human rights organisations, including B’Tselem, are gathering evidence for such legal actions and advance the argument that an Israeli initiative has the national benefit of undermining the international calls for legal action.

This Israeli initiative, even if nothing follows in the way of legal action, as seems almost certain due to political constraints, has significance. It will lend credence to the controversial international contentions that criminal indictment and prosecution of Israeli political and military leaders and war crimes perpetrators should take place in some legal venue. If politics blocks legal action in Israel, then the implementation of international criminal law depends on taking whatever action is possible in either an international tribunal or foreign national courts, and if this proves impossible, then by convening a non-governmental civil society tribunal with symbolic legal authority.

Political will is lacking

What seems reasonably clear is that despite the clamour for war crimes investigations and accountability, the political will is lacking to proceed against Israel at the inter-governmental level, whether within the UN or outside. The realities of geopolitics are built around double standards when it comes to war crimes. It is one thing to proceed against Saddam Hussein or Slobodan Milosevic, but quite another to go against George W Bush or Ehud Olmert. Ever since the Nuremberg trials after the second world war, there exists impunity for those who act on behalf of powerful, undefeated states and nothing is likely to challenge this fact of international life in the near future, thus tarnishing the status of international law as a vehicle for global justice that is consistent in its enforcement efforts. When it comes to international criminal law, there continues to exist impunity for the strong and victorious, and potential accountability for the weak or defeated.

Civil society tribunals

It does seem likely that civil society initiatives will lead to the establishment of one or more tribunals operating without the benefit of governmental authorisation. Such tribunals became prominent in the Vietnam war when Bertrand Russell took the lead in establishing the Russell Tribunal. Since then the Permanent Peoples Tribunal based in Rome has organised more than 20 sessions on a variety of international topics that neither the UN nor governments will touch.

In 2005 the World Tribunal on Iraq, held in Istanbul, heard evidence from 54 witnesses, and its jury, presided over by the Indian novelist Arundhati Roy, issued a Declaration of Conscience that condemned the US and Britain for the invasion and occupation of Iraq, and named names of leaders in both countries who should be held criminally accountable.

The tribunal compiled an impressive documentary record as to criminal charges, and received considerable media attention, at least in the Middle East. Such an undertaking is attacked or ignored by the media because it is one-sided, and lacking in legal weight, but in the absence of formal action on accountability, such informal initiatives fill a legal vacuum, at least symbolically, and give legitimacy to non-violent anti-war undertakings.

Update at the end of 2023

Note added December 9, 2023: The civil society would be invited to call for a ceasefire in Gaza in a global referendum sponsored by the United Nations, according to an approach suggested to the UN Secretary-General in a letter from Mouvement de la Paix.

Note added December 30, 2023: South Africa has asked the International Court of Justice to rule on Israeli genocide against Palestine.

New Realities of Israel/Palestine in the Trump Era: Settler Colonial Destinies in the 21st Century

Michael Moore: From the Rubble Rises 22 Powerful Voices

With Israel’s destruction of Kamal Adwan Hospital, UN rapporteur calls for global medical boycott

Activists Occupy Canadian Parliament Building to Protest Gaza War & Arming of Israel

Companies Profiting from the Gaza Genocide

UN General Assembly demands Israel end ‘unlawful presence’ in Occupied Palestinian Territory

Israeli General Strike Protests Netanyahu’s ‘Cabinet of Death’

Complicity in Genocide—The Case Against the Biden Administration

Michael Moore: I Now Bring You the Voices of a New Generation

South Africa requests ICJ emergency orders to halt “unspeakable” Gazan genocide

Last Days of Hearings at the International Court of Justice on the Israeli Occupation of Palestine

World Court to Review 57-Year Israeli Occupation

USA: 200+ Unions Launch Network to Push for Gaza Cease-Fire

BDS Movement: Act Now Against These Companies Profiting from the Genocide of the Palestinian People

South Africa Initiates Case Against Israel at International Court of Justice

Israel-Palestine: The Role of International Justice

BRICS Countries Call to End Israel’s Aggression in Gaza

Mazin Qumsiyeh: Are we being duped to focus only on Gaza suffering?

UN Rights Chief Says Israel’s Collective Punishment in Gaza Is a War Crime

1,500+ Israelis Urge ICC Action on ‘War Crimes and Genocide’ in Gaza

Elders warn of consequences of “one-state reality” in Israel and Palestine

The Western Sanctions That Are ‘Choking’ Syria May Be Crimes Against Humanity

Ceasefire can’t hide scale of destruction in Gaza, UN warns, as rights experts call for ICC probe

Human Rights Watch : Abusive Israeli Policies Constitute Crimes of Apartheid, Persecution

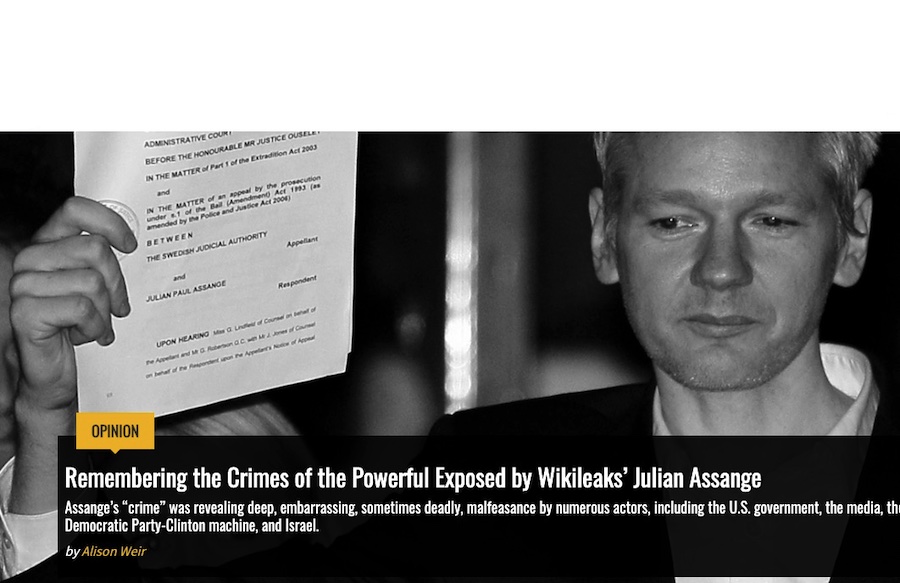

Remembering the Crimes of the Powerful Exposed by Wikileaks’ Julian Assange

US Media Ignore—and Applaud—Economic War on Venezuela

ICC judges order outreach to victims of war crimes in Palestine