FREE FLOW OF INFORMATION

An article by Kati Hinman for NACLA (North American Congress on Latin America

On Colombia’s Pacific coast, paramilitary violence has engulfed Afro-communities and their leaders in the wake of the peace accords. But resistance at the grassroots level remains strong.

Photo source: comité paro civico Buenaventura facebook

On April 17, three community leaders from the Naya River, south of the city of Buenaventura on Colombia’s Pacific Coast, were kidnapped by an unnamed armed group. The group was also searching for another leader, Iber Angulo Zamora. On May 5, Angulo Zamora was kidnapped from a boat in the presence of officers from the Human Rights Ombudsmen. The two attacks generated terror along the Naya, trapping people in their villages or displacing them to the city of Buenaventura.

Men claiming to be dissidents of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) released a video in June, claiming responsibility and stating that the leaders were killed because of their involvement in “illegal activities,” most likely referring to drug-trafficking. There has been no evidence to substantiate the accusations against the leaders, but residents have been reluctant to suggest motives for the attack in fear of repercussions. Paramilitary groups are also present in the zone, and there have been reports of combat between armed groups, adding to the danger and confusion for civilians.

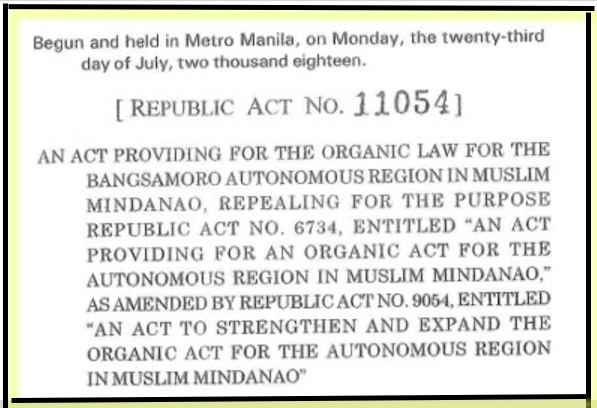

These attacks are unfortunately only a few examples of the violence that continues to plague the majority Afro-Colombian communities in the city of Buenaventura and the surrounding rural areas, despite the reforms promised in the 2016 Peace Accords between the FARC and the Colombian government. The Peace Accords has been hailed as one of the most progressive and thorough peace agreements in history, promising rural land reform and development, a comprehensive effort to replace illegal crops such as coca with legal sources of income, reparations to the conflict’s victims—ranging from individual payments to collective land titles and social projects—and truth and justice commissions. However, the first two years of implementation have fallen behind expectations, especially for Colombia’s Afro and Indigenous communities, who are some of the principal victims of the conflict.

The Naya River zone is home to 64 Afro-Colombian and two Indigenous communities. Afro-Colombians have lived on the river for over 300 years, and were first brought there as slaves to work in mines. After the abolition of slavery in Colombia, they created independent settlements in the region. After paramilitaries committed a brutal massacre in 2001, killing more than 70 people, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights implemented a series of precautionary measures to protect these communities. Today, Afro-Colombian communities along the Naya are governed by one democratically elected Community Council. Just three years ago, the Community Council was granted a collective title to the 64 communities’ lands under Law 70, which protects the ancestral territories of Afro-Colombians.

Government response to the recent violence has been slow and mainly focused on further militarizing the zone by sending in more troops and pushing for additional military bases within the communities. Community leaders advocated for a thorough criminal investigation into the crimes and respect for their rights as civilians to remain neutral in the conflict. They are concerned that military presence in their public spaces might put them at risk for more attacks.

The Battle for Puente Nayero

The continued violence is not limited to the rural areas around Buenaventura. On July 1st, a group of known paramilitaries entered Puente Nayero, a humanitarian space in the city of Buenaventura, where they remained for several hours as residents hid in their homes. Humanitarian spaces are designed as places where civilians can remain neutral and free from engaging with armed actors. Puente Nayero, created four years ago in response to terror and brutality as successor paramilitary groups were dividing the city, received legal and financial support from the Inter-Church Commission of Peace and Justice, a Colombian human rights organization, and protections from the Inter-American Court of Human Rights.

Elisabeth [last name withheld] was one of the community leaders behind the space. “One thing that pushed me personally [to act] was my son,” she said. “He is very big, people think he is older than he is, and they started looking at him to become part of the [paramilitary] structure [when] he was 13 years old.”

The protections for the space call on the Colombian government to adapt effective measures to preserve the lives of the 302 families who live in the humanitarian space and to respect their rights as civilians. Elisabeth explained that through the declaration of the humanitarian space and better community organizing, they were able to decrease the violence and remove a “chop-house” from their street, which were houses utilized by paramilitaries to torture and murder.

(Continued in right column)

What is happening in Colombia, Is peace possible?

(Continued from left column)

Elisabeth still feels that as a leader, just stepping outside the humanitarian space leaves her feeling vulnerable and scared for her life. She has reason to fear; social leaders in Colombia are being targeted and killed at alarming rates. In January of 2018, Temistocles Machado, an Afro-Colombian activist, was killed in the city. Machado was one of the most prominent leaders of the civil strike that took place in Buenaventura in 2017.

Buenaventura is home to Colombia’s principal port, surrounded by a Free Trade Zone that allows most of the wealth generated by the port to flow directly to international companies. Corruption is rampant in the city, and in 2017 64% of the population lived in poverty, with unemployment at 62%. When the violence between warring paramilitary groups in Buenaventura escalated in 2013-2014, much of it occurred in neighborhoods that were part of development plans for a tourist boardwalk, airport, and other projects that would have to displace residents.

José, a 67-year-old from the humanitarian space, explained that the paramilitaries, with support of corporations, “wanted us to de-occupy this territory [Puente Nayero] so they could take it, so they started doing things to terrify us, to get rid of us.” The residents of Puente Nayero still worry that city development projects might lead to their displacement, and the recent presence of paramilitaries in the neighborhood has elevated these concerns.

The battle over land rights is an ongoing and central concern for Afro-Colombians in Buenaventura and the surrounding rural regions. Colombia has the highest rate of inequality in land ownership in Latin America, with just 0.4% of holdings encompassing two-thirds of agricultural land. Meanwhile, 60% of Colombian farmers have no formal titles to their land. According to the United Nations Refugee Agency, over 7.6 million Colombians are internally displaced, forced to leave their homes because of violence or threats from armed groups, many without formal titles to prove their ownership and right to return.

To address this, land restitution was a central tenet of the Peace Accords. But many people remain uncertain that they will recover their ancestral lands. The rural Afro-Colombian community of La Esperanza was displaced to Buenaventura due to paramilitaries in 2004. Although they won collective title to their land under Law 70 in 2008, as well as provisional protective measures from the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, their land has been parceled off and sold, and community leaders stated that local politicians were involved and now own some of the plots. Florenina, a community leader, emphasized repeatedly that logging and construction companies were responsible for the damage to their lands since their displacement. “True peace for me is defined as when people can return to their lands, when they are given reparations, beginning with the land because the territory is very damaged.”

Sara, a young woman and teacher on the Naya, is particularly disappointed with programs intended to combat illicit crop substitution, referring to financial support and training for farmers to replace coca with other crops, and the Development Plans with a Territorial Focus (PDETs). The PDETs are rural development plans for the areas hardest hit by the conflict, based in the community’s needs and priorities. These plans are critical for the Naya, as the river is utilized by criminal networks, not only for illegal mining and coca cultivation but also for the production and transit of cocaine directly to international waters. Other community members I spoke with agreed with Sara, adding that the government has not helped to provide needed social services, such as health centers and schools.

There is also concern that the “peace” era will bring extractive development projects that could drive the people of the Naya from their lands. Despite the Community Council’s collective land title, the Colombian government still holds legal rights over anything beneath the earth’s surface. Community leaders worry that their authority might be usurped to move forward with large-scale mining projects, since the area is rich with gold. The natural riches in their territory have become a source of danger for the communities.

As people have become disenchanted with the implementation of the accords, they have continued to build peace in their own ways. In May 2017, the residents of Buenaventura and the surrounding area shut down the city in a civil strike, demanding a recognition of their rights. Despite the assassination of leaders such as Temistocles Machado, the strike committee continues to implement the agreement reached with the government, which includes overseeing the funds to build a hospital and an aqueduct for the city.

Residents have also created local peace-building initiatives. For example, Niridia, a member of a collective of 300 women in the Naya River region, helps run political advocacy workshops and leadership schools, focusing on various themes from globalization and multiculturalism to gender and nature. “We are all family members of disappeared persons,” she said of the collective. “Although we might consider our family members dead, they still give us the possibility to exchange the tears for smiles for new generations.”

Sara, the teacher, said that keeping up the traditions that communities on the Naya have practiced for 300 years is an important part of peace-building. As an educator, she works to ensure an emphasis on protecting the environment. They use practical lessons to teach the children how to take care of their water and natural resources. In Puente Nayero, leaders continue to organize around their principles of dialogue and fair treatment.

President-elect Iván Duque has been critical of the Peace Accords and seems committed to obstructing their implementation, generating further doubt that there will be reparations and justice for Afro-Colombian victims on the national level. This has not deterred grassroots commitment to local peace-building processes, giving people hope and strength while they continue to resist violence and advocate for their rights and their lands.