DISARMAMENT & SECURITY .

An article by Leonardo Flores published on April 7 in Common Dreams ( licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 License.)

On April 1, the Trump administration hijacked a COVID-19 press conference to announce the deployment of U.S. Navy vessels and other military assets towards Venezuela. According to Defense Secretary Mark Esper, “included in this force package are Navy destroyers and littoral combat ships, Coast Guard Cutters, P.A. patrol aircraft, and elements of an Army security force assistance brigade”, while General Mark Milley, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, added that there are “thousands of sailors, Coast Guardsman, soldiers, airmen, Marines involved in this operation.” The pretext is a counter-narcotics operation to follow up on the Department of Justice’s March 26 indictment of President Nicolás Maduro and 13 others on narcoterrorism charges. This indictment is politically motivated and has been critiqued in depth.

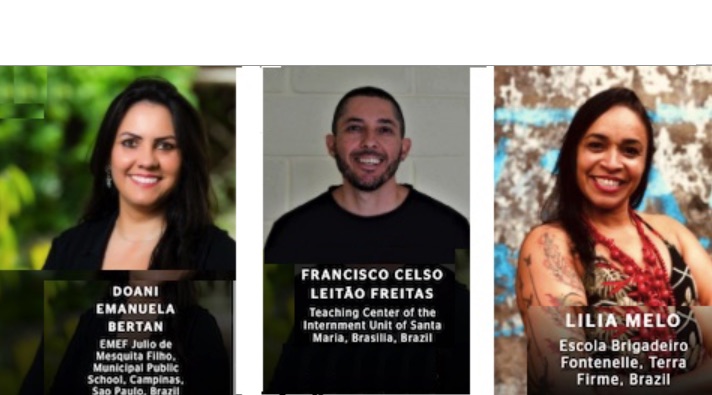

Venezuelan soldiers prepare for war… against COVID-19. (Photo: Twitter @Planifica_Fanb)

In between the sticks of indictments and the deployment, the Trump administration seemingly offered a carrot: a proposed “democratic transition framework” that would progressively see the sanctions lifted after the resignations of Maduro and Juan Guaidó, the installation of a “Council of State” and elections in which neither Maduro nor Guaidó can participate. This proposal, which is more of a poison pill than a carrot, was immediately rejected by Venezuelan opposition politicians and the government. The plan is unconstitutional, it violates Venezuelan sovereignty (insofar as it is a tacit acceptance that illegal sanctions imposed on the U.S. should be allowed to dictate the country’s domestic affairs), and it runs counter to the ongoing dialogue in Venezuela that is getting closer every day to establishing a new National Electoral Council and setting a date for legislative elections. Henri Falcón – a former opposition presidential candidate – criticized the plan and said an agreement cannot be imposed, that a “solution in Venezuela is between Venezuelans.” It was also called into question by House Foreign Affairs Committee Chair Eliot Engel, who called the approach “an utterly incoherent policy”, as it came days after the Department of Justice said nothing would stop them from moving forward with the narcoterrorism case.

The Distraction from and Weaponization of COVID-19

It seemed as though Venezuela was finally moving forward towards a negotiated solution to its political crisis, yet the naval deployment may sabotage the dialogue, as it was partially designed to do. The other purposes of the deployment were to distract from COVID-19 at home and to take advantage of the epidemic in order to increase the pressure on the Maduro government.

It was a bizarre scene that played out on April 1 during the press conference announcing the deployment. CNN was covering the conference live, believing it to be about the pandemic; this belief was reasonable, as it was marketed as a coronavirus briefing and it came a day after that the government released an estimated COVID-19 death toll of anywhere between 100,000 to 240,000. As the White House argued that drug traffickers might exploit the virus, CNN cut away from the discussion of the “seemingly unrelated counternarcotics operations.” That night Twitter was flooded with #WagTheDog tweets, a hashtag indicating that Trump was trying to drum up a war to distract from the incompetent handling of the pandemic.

A senior Pentagon official even told Newsweek that Trump was “using the operation to redirect attention.” By April 3, the White House was pitching the idea that fighting the drug trade would somehow help fight the coronavirus, leading military officials to express “shock” at the conflation between the war on drugs and COVID-19. Of course, as shown by recent events onboard the USS Theodore Roosevelt, whose captain was dismissed after the virus rapidly spread amongst his sailors, U.S. service members are being exposed to greater risk of contagion by this massive deployment to the Caribbean. They are exposed on crowded ships and they are exposed on land at the nine U.S. military bases in Colombia. This is especially true considering that in Colombia, the COVID-19 response has been so poor that in late March, one of the country’s two machines for analyzing the results of coronavirus testing was knocked offline for 24 hours.

(continued in right column)

US war against Venezuela: How can it be prevented?

(continued from left column).

Apparently, this risk is acceptable to the Trump administration, as it sees an opportunity to weaponize the pandemic, using the instability and chaos it is causing to further its regime change goals. William Brownfield, former U.S. ambassador to Venezuela and one of the architects of the regime change policy, characterized “the sanctions, the price of oil, the pandemic, the humanitarian crisis” and the migration of so many Venezuelans as a “perfect storm” to pressure Maduro with the “non-negotiable” offer that he must leave.

The Possible Consequences of the Naval Deployment

The Trump administration has not given details as to what “counter-narcotics operations” might look like off Venezuelan waters, but it is very clearly a provocation. There is also the possibility of false flag or false positives, in which any incident between the U.S. and Venezuelan navies could be used as a pretext to war, much like the Gulf of Tonkin incident was used to draw the U.S. into Vietnam.

There are other possible scenarios that could have devastating economic consequences. The Venezuelan government is concerned that everything from imports to oil exports could be intercepted or seized by the U.S. Navy. This is a valid concern, as the Pentagon has claimed – without offering any evidence – that drugs are trafficked “using naval vessels from Venezuela to Cuba.” Given the U.S. government’s targeting and sanction of ships that transport oil from Cuba to Venezuela, it hardly beggars belief that Venezuelan oil tankers could be boarded by the U.S. military.

As piracy is apparently back in fashion, with the U.S., among other countries, seizing COVID-19 equipment that has already been paid for by smaller countries, it would not be surprising to see the U.S. seize Venezuelan oil or other assets on the high seas, particularly given Trump’s penchant for saying that other countries will pay for U.S. military expenditures (whether it’s the wall on the Mexico border, NATO security spending or the threatened plundering of Iraqi or Syrian oil). It is an open question whether the world would allow the Venezuelan people to essentially be starved by this type of blockade.

The Danger of Military Action

Trump has been threatening military action against Venezuela since August 2017 and a naval blockade since August 2019. The deployment of the Navy towards Venezuela is the first step in backing up both threats. According to the AP, it is “one of the largest U.S. military operations in the region since the 1989 invasion of Panama to remove Gen. Manuel Noriega from power and bring him to the U.S. to face drug charges.” The indictment of Maduro also draws comparisons to Noriega, himself indicted on similar charges. Senator Marco Rubio – arguably the biggest backer of violent regime change in Washington – tweeted pictures of Noriega in a not-so-veiled threat to President Maduro last year. The ties to Panama go even deeper: Attorney General William Barr and Trump’s Special Representative on Venezuela, Elliott Abrams, both worked for the Bush administration as it ramped the pressure up on Noriega.

Yet the overthrow of Noriega wasn’t achieved with sanctions, indictments or a naval deployment, it was achieved by a U.S. invasion. Furthermore, Venezuela isn’t Panama. It is a substantially bigger country, it is stronger militarily, it has important allies in China and Russia, and it counts with a 3-million-person militia.

This latter point is often overlooked or dismissed but understanding the seriousness of this militia is key to understanding the political landscape of Venezuela. In February 2019, as rumors swirled of a possible invasion from Colombia, members of the militia occupied key bridges along the border, fully prepared to risk their lives, as one militia member said in a recent documentary. The militia is part of the identity of chavismo, the left-wing revolutionary movement that backs Maduro and takes its inspiration from former Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez. For most on the left in Venezuela, there are no more than two degrees of separation from the militia: they either form part of it, they know someone in the militia, or they know someone who knows someone in the militia.

The implications of this should be evident: Venezuela has a substantial population that will resist any invasion or coup. This isn’t mere rhetoric; the biggest popular uprising in Venezuela of the past 30 years occurred on April 12 and 13, 2002, when Venezuela’s poor, working-class, black, brown and indigenous people took to the streets to demand the return of ousted president Hugo Chávez, reversing a right-wing coup within 48 hours. (Of note: Elliott Abrams was in the George W. Bush administration at the time and “gave a nod” to the coup, according to The Guardian.)

What this all means is that Venezuela won’t be like Panama, where there was little resistance. If the worst happens and a war breaks out, more apt comparisons would be Afghanistan, Syria or Iraq, countries in which the U.S. spent billions for regime change at a disastrous cost to human lives and regional stability. The Trump administration’s dangerous deployment should be challenged by Democrats and Republicans alike, but so far, no major politician has criticized the maneuver. Hopefully the American people will read the message of peace sent by President Maduro and urge the U.S. government to fight covid, not Venezuela.