EDUCATION FOR PEACE .

An article by Jeff Schwaner in The News Leader

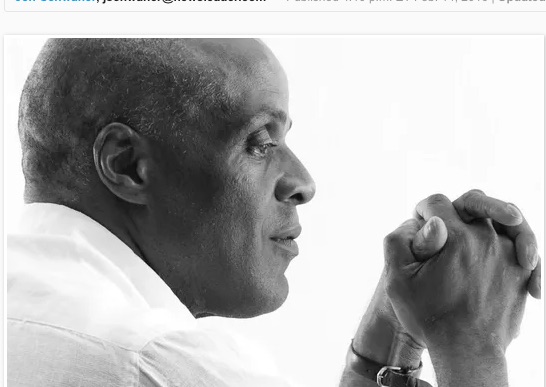

“We all have poetry in us.” This is the first thing Neal Hall wants to be clear about. The renowned African American poet and medical doctor reads from his work at 7:30 p.m. Thursday, Feb. 18, in the Carter Center for Worship and Music at Bridgewater College.

While Hall is identified as an African-American poet, the demand for him to accept reading engagements is not limited to Black History Month. Hall has performed poetry readings throughout the United States and internationally in Canada, France, Indonesia, Italy, Jamaica, Kenya, Morocco, Nepal and India. He participated in Bridgewater College’s 2015 International Poetry Festival last January.

Photo: SUBMITTED / Steve Ladner

The Bridgewater reading is sandwiched between trips to India and Italy, both chock full of readings and public addresses.

In an email interview, Hall responded to questions of how being an African-American contributed to his evolution as a poet.

“What comes with the label of African-American or Black is this institutionalized, generational legacy of a trail of tears we are forced to walk. This trail and our tears make us uniquely sensitive to the suffering and exploitation of all men and women. It qualifies us and challenges us to stand up to be the true standard bearers and guardians of freedom for all,” Hall writes. “My poetry is influenced by and speaks not just to the surface pain of injustice and inhumanity, but digs deep into that pain, into the genteel socio-political-economic- religious constructs used to blur the common lines of cause that is our shared story. This shared story, the poetry reminds us, should unite us in our common struggle to be free.”

When asked if being identified as an African-American poet could be an obstacle to his expression, Hall responded, “If it is an identifier and/or identity, I did not create it to identify me nor to limit me. As such, one has to ask the larger question: Who created it for me and for what reasons?”

Across the work of four books, Hall’s poetic voice is insistent on his readers realizing their own will to be free, but also identifies the oppressor in its various institutional and cultural forms. “When you see that you are not free / you must say and do, to be free,” he writes in one of the poems from his first book. In the poems “White Man Asks Me” (“A white man asked me to / be less than a man so that he could / find a face-saving way out”) and “Dr. Nigga” (“…save my life / without changing my life / when my white life codes blue”) Hall directly confronts and reveals the structure of racism.

For some of his readers this is difficult but necessary: “knowing that you are the cause and then the painful act of changing your behavior which has afforded and enriched you (relatively speaking) generating socio-economic advantages over your brothers and sisters.”

(continued in right column)

Question for this article:

How can poetry promote a culture of peace?

Are we making progress against racism?

(continued from left column)

Poetry is one way to face such formidable challenges. “We are the only obstacle getting in the way of our deeper expressions. I find my deepest expression in breathing air in and out deeply in the full realization of my connection, brotherhood and common humanity with all that exists. This connection, this brotherhood, our common humanity is seamless. It is the greed of man exploiting our fabricated man-made differences that has created seams in us, to divide us from our oneness. There is nothing complex nor complicated about man’s gluttony.”

Hall earned his undergraduate degree from Cornell University and an M.D. from Michigan State University. He received his surgical subspecialty training in ophthalmology at Harvard University’s Medical School and was in private practice for more than 20 years in Flourtown, Pa.

Hall is the author of four books of poetry, Nigger For Life, Winter’s A’ Coming Still, Appalling Silence and Where Do I Sit, that deal with oppression and exploitation in American society.

The poet’s charismatic reading style has captured international audiences that go far beyond what any label as an African-American poet might mean. I asked him about the connection. “I have learned from my travels that the oppressors, oppression and their methods are the same all over the world and thus those who suffer from them are connected,” Hall wrote. “The oppressed all understand that their oppression is based in large part on gluttony/greed. The need for a source of continuous cheap labor and to rob people of their substance, their lands and resources often under the guise of religion, democracy, freedom, education, tradition, culture and self-serving charity.”

Few poets read in public as often as Hall. And Hall recognized this activity as a watershed moment in his development as a poet. “There in real time with the poetry of your heart and mind flowing from your mouth, you see yourself touching, moving audiences’ hearts and minds to feel and live the poetry you’ve lived and are re-living in the readings before them. There in real time, I learned to live in my poetry as much as my poetry lives in me.”

I asked him how that speaks to the mysterious relationship between writer and poem and reader.

“It is no mystery. What people get from your poetry is not only what you give them, but also the life experiences they bring to your poetry. And the life experience they bring to your poem can illuminate the words and impact far more — or less — in them than in you or your intent.

So when readers respond in a very surprising manner to a poem, does it make him feel differently about the poem?

“No. The poem is my poem and my experience. I can only feel what I bring to it and it to me. On the other hand, I do feel honored and grateful that others bring their different life experiences into play when reading about and connecting with my life experiences through my poetry. We are, as I have said, seamless! Poetry can bear witness to erase the seams man creates in us.”

Hall writes in one of his poems, “We are socialized and emotionalized to see / our plight in black and white.”

No such adhering to stereotype in Hall’s work.

The program is free and open to the public.