. . DESARME Y SEGURIDAD . .

De la página web de la Fundación Cultura de Paz

Nosotros, personas e instituciones profundamente preocupadas por la situación del mundo, en particular por los procesos sociales y medioambientales potencialmente irreversibles, y por la carencia de un multilateralismo democrático respetado por todos y eficaz, imprescindible para la gobernanza planetaria en tiempos de celeridad y complejidad extraordinarias,

URGIMOS

A unirse a esta declaración conjunta con el fin de contribuir a la apremiante adopción de las siguientes medidas cuyos fundamentos se hallan en documento I y documento II adjuntos.

1- Medioambiente

Las presentes tendencias, fruto de un lamentable sistema económico que solo tiene en cuenta los beneficios inmediatos, deben enderezarse con urgencia para evitar puntos de no retorno.

Tanto el presidente Obama –“somos la primera generación que sufre las consecuencias del cambio climático y la última que puede tomar medidas para solucionarlo”- como el Papa Francisco –“(…) no estamos hablando de una actitud opcional sino de una cuestión básica de justicia ya que la Tierra que recibimos pertenece también a las que vendrán”- han alertado con sabiduría y liderazgo sobre las impostergables acciones a adoptar en relación al cambio climático. El futuro debe ser inventado. La capacidad creadora distintiva de los seres humanos es nuestra esperanza. “Situaciones sin precedentes requieren soluciones sin precedentes”, advirtió Amin Maalouf.

Vivimos un momento crucial de la historia de la Humanidad en el que tanto su número como la naturaleza de sus actividades influyen en la habitabilidad de la Tierra (antropoceno).

Los intereses de todo orden deben subordinarse al profundo conocimiento de la realidad. La comunidad científica, guiada por los “principios democráticos” que con tanta clarividencia establece la constitución de la UNESCO, debe aconsejar a los gobernantes (a escala internacional, regional, nacional y municipal) las acciones a adoptar no solo en una esencial funcion de consejo sino de anticipación. Saber para prever, prever para prevenir.

Está claro que disponemos actualmente de diagnósticos adecuados pero que no desembocan en lo que realmente importa: el tratamiento oportuno.

Los medios de comunicación y las redes sociales deben procurar sin pausa que se forme, en un gran clamor, una conciencia solidaria y responsable, adoptándose a todas las escalas las resoluciones colectivas y personales- incluyendo cambios radicales en las entidades- que puedan detener, antes de que sea demasiado tarde, el deterioro presente.

El presidente Nelson Mandela nos recordó que “el supremo compromiso de cada generación es atender debidamente a la siguiente”.

2-Desigualdades sociales y extrema pobreza

Es humanamente intolerable que cada día mueran de hambre y desamparo miles de personas, la mayoría de ellas niñas y niños de 1 a 5 años de edad, al tiempo que se invierten en armas y gastos militares 3.000 millones de dólares. Sobre todo cuando, como acontece ahora, se han reducido, indebida y dolosamente, los fondos destinados al desarrollo sostenible y humano. La insolidaridad de los más prósperos con los menesterosos alcanza límites que no deben seguirse tolerando. Para la transición desde una economía anti-ecológica de especulación, deslocalización productiva y guerra a una economía basada en el conocimiento para un desarrollo global sostenible y humano, y de una cultura de imposición, violencia y guerra a una cultura de la palabra, de conciliación, alianza y paz, debe procederse de forma inmediata a prescindir de los grupos plutocráticos (G7, G8, G20) y reponer los valores éticos en el centro del comportamiento cotidiano.

3-Eliminación de la amenaza nuclear y desarme para el desarrollo

La amenaza nuclear sigue consituyendo un inverosímil y éticamente insensato y siniestro peligro. El desarme para el desarrollo, bien regulado, no solo permitiría garantizar la seguridad internacional sino que proporcionaría los fondos necesarios para un desarrollo global y la puesta en práctica de las prioridades de las Naciones Unidas (alimentación, agua, salud, medioambiente, educación para todos toda la vida, investigación científica e innovación, y paz.).

(El artículo continúa en el lado derecho de la página)

( Clickear aquí para la version inglês )

Proposals for Reform of the United Nations: Are they sufficiently radical?

(El artículo continúa desde la parte izquierda de la página)

Por razones tan relevantes y urgentes

PROPONEMOS,

La celebración de una sesión extraordinaria de la Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas, que adopte las apremiantes medidas necesarias, tanto sociales como medioambientales, y establezca, además, las directrices para la refundación de un sistema multilateral democrático. El “nuevo Sistema UN”, con una Asamblea General compuesta por el 50% de representantes de la sociedad civil, añadiendo el actual Consejo de Seguridad, un Consejo Medioambiental y un Consejo Socioeconómico ha sido

estudiado en profundidad. En todos los casos, no habría veto pero sí voto ponderado.

A la vista de los precarios resultados alcanzados en el cumplimiento de los ODM (Objetivos del Milenio), nadie confía, vista la insolidaridad actual, las crecientes desigualdades sociales y la subordinación a los grandes consorcios mercantiles, en la puesta en práctica efectiva de los ODS (Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible) que se formularán el presente mes de septiembre.

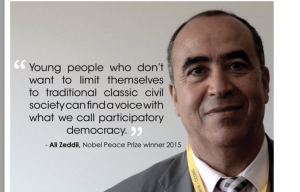

La solución es la democracia participativa e inclusiva, en la que todas las dimensiones de la economía estén subordinadas a la justicia social.

Jose Luis Sampedro dejó este fantástico legado a los jóvenes: “Tendréis que cambiar de rumbo y nave”. En el informe anexo (I) se detallan recientes hechos y proyectos que constituyen un buen augurio. La Humanidad, ahora que ya puede expresarse libremente gracias a la tecnología digital, ha adquirido una conciencia global y cuenta –piedra angular de la nueva era- con un número progresivamente mayor de mujeres en la toma de decisiones. Se avecina la inflexión histórica que le permitirá llevar en sus manos las riendas del destino común.

* * * * * * * * *

Signatarios a partir de septiembre 2015

Federico Mayor (Presidente de la Fundación Cultura de Paz y ex Director General de UNESCO)

Mikhail Gorbachev (Ex Presidente de la Unión Soviética; Presidente de Green Cross

International y del World Political Forum)

Mario Soares (Ex Presidente de Portugal y Presidente de la Fundaçao Mario Soares)

Garry Jacobs (Director Ejecutivo de la World Academy of Art & Science)

Colin Archer (Secretario General), Ingeborg Breines (Co-Presidenta) and Reiner Braun (CoPresidente) del International Peace Bureau

Roberto Savio (Fundador y Presidente de IPS-International Press Service).

François de Bernard (Presidente y Co-fundador de GERM (Group for Study and Research on

Globalization)