FREE FLOW OF INFORMATION

Distributed by email from Rabbi Michael Lerner, Tikkun Magazine

Daniel Berrigan was one of the most inspiring figures of the anti-war and social justice movements of the past fifty years. He died on Saturday, April 30, 2016, and will be sorely missed by all of us who knew him. I was first introduced to him by my mentor Abraham Joshua Heschel in 1968 when he and Heschel and Martin Luther King had become prominent voices in the Clergy and Laity Against the War in Vietnam. He told me that he had been inspired by the civil disobedience and militant demonstrations that were sweeping the country in 1966-68, many of them led by Students for a Democratic Society (at the time I was chair of the University of California Berkeley chapter). . .

Over the course of the ensuing 48 years I was inspired by his activism and grateful for his support for Tikkun magazine. Heschel told me how very important Dan was for him–particularly in the dark days after Nixon had been elected and escalated the bombings in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. Those of us who were activists were particularly heartened by his willingness to publicly challenge the chicken-heartedness and moral obtuseness of religious leaders in the Catholic, Protestant and Jewish world who privately understood that the Vietnam war was immoral but who would not publicly condemn it and instead condemned the nonviolent activism of the anti-war movement because we were disobeying the law, burning our draft cards, disrupting the campus recruitment into the CIA and the ROTC, and blocking entrance into army recruitment centers and the Pentagon!

Here is a brief summary of Berrigan’s achievements as written for the Catholic magazine AMERICA He co-founded the Catholic Peace Fellowship and the interfaith group Clergy and Laity Concerned about Vietnam, whose leaders included Martin Luther King Jr., Richard John Neuhaus and Abraham Joshua Heschel.

Berrigan regularly corresponded with Thomas Merton, Dorothy Day and William Stringfellow, among others. He also made annual trips to the Abbey of Gethsemani, Merton’s home, to give talks to the Trappist novices.

In Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander (1966), Merton described Berrigan as “an altogether winning and warm intelligence and a man who, I think, has more than anyone I have ever met the true wide- ranging and simple heart of the Jesuit: zeal, compassion, understanding, and uninhibited religious freedom. Just seeing him restores one’s hope in the Church.”

A dramatic year of assassinations and protests that shook the conscience of America, 1968 also proved to be a watershed year for Berrigan. In February, he flew to Hanoi, North Vietnam, with the historian Howard Zinn and assisted in the release of three captured U.S. pilots. On their first night in Hanoi, they awoke to an air-raid siren and U.S. bombs and had to find shelter.

As the United States continued to escalate the war, Berrigan worried that conventional protests had little chance of influencing government policy. His brother, Philip, then a Josephite priest, had already taken a much greater risk: In October 1967, he broke into a draft board office in Baltimore and poured blood on the draft files.

Undeterred at the looming legal consequences, Philip planned another draft board action and invited his younger brother to join him. Daniel agreed.

On May 17, 1968, the Berrigan brothers joined seven other Catholic peace activists in Catonsville, Md., where they took several hundreds of draft files from the local draft board and set them on fire in a nearby parking lot, using homemade napalm. Napalm is a flammable liquid that was used extensively by the United States in Vietnam.

Daniel said in a statement, “Our apologies, good friends, for the fracture of good order, the burning of paper instead of children, the angering of the orderlies in the front parlor of the charnel house. We could not, so help us God, do otherwise.”

(Article continued in the column on the right)

Where in the world can we find good leadership today?

(Article continued from the column on the left)

Berrigan was tried and convicted for the action. When it came time for sentencing, however, he went underground and evaded the Federal Bureau of Investigation for four months.

“I knew I would be apprehended eventually,” he told America in an interview in 2009, “but I wanted to draw attention for as long as possible to the Vietnam War and to Nixon’s ordering military action in Cambodia.”

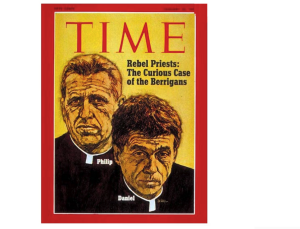

The F.B.I. finally apprehended him on Block Island, R.I., at the home of theologian William Stringfellow, in August 1970. He spent 18 months in Danbury federal prison, during which he and Philip appeared on the cover of Time magazine.

The brothers, lifelong recidivists, were far from finished.

On Sept. 9, 1980, Daniel and Philip joined seven others in busting into the General Electric missile plant in King of Prussia, Pa., where they hammered on an unarmed nuclear weapon—the first Plowshares action. They faced 10 years in prison for the action but were sentenced to time served.

In his courtroom testimony at the Plowshares trial, Berrigan described his daily confrontation with death as he accompanied the dying at St. Rose Cancer Home in New York City. He said the Plowshares action was connected with this ministry of facing death and struggling against it. In 1984, he began working at St. Vincent’s Hospital, New York City, where he ministered to men and women with H.I.V.-AIDS.

“It’s terrible for me to live in a time where I have nothing to say to human beings except, ‘Stop killing,’” he explained at the Plowshares trial. “There are other beautiful things that I would love to be saying to people.”

In 1997 he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Berrigan’s later years were devoted to Scripture study, writing, giving retreats, correspondence with friends and admirers, mentorship of young Jesuits and peace activists, and being an uncle to two generations of Berrigans. He published several biblical commentaries that blended scholarship with pastoral reflection and poetic wit.

“Berrigan is evidently incapable of writing a prosaic sentence,” biblical scholar Walter Brueggemann wrote in a review of Berrigan’s Genesis (2006). “He imitates his creator with his generative word that calls forth linkages and incongruities and opens spaces that bewilder and dazzle and summon the reader.”

From 1976 to 2012, Berrigan was a member of the West Side Jesuit Community, later the Thompson Street Jesuit Community, in New York City. During those years, he helped lead the Kairos Community, a group of friends and activists dedicated to Scripture study and nonviolent direct action.

Even as an octogenarian, Berrigan continued to protest, turning his attention to the U.S. wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the prison in Guantánamo Bay and the Occupy Wall Street movement. Friends remember Berrigan as courageous and creative in love, a person of integrity who was willing to pay the price, a beacon of hope and a sensitive and caring friend.

(This summary of one part of his achievements was written by Luke Hansen, S.J., a former associate editor of America, now a student at the Jesuit School of Theology of Santa Clara University, Berkeley, Calif.).

We at Tikkun magazine, the voice of Jewish progressives, liberals, radicals and anti-capitalist non-violent revolutionaries, will deeply mourn the loss of our brother Daniel Berrigan. Dan was a true spiritual progressive, and it was a great honor for us when he joined the Advisory Board of the Network of Spiritual Progressives. His memory will always be a blessing (z’l=zeycher tzadik liv’racha).

–Rabbi Michael Lerner