. . SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT . .

An article from Araz Hachadourian, Yes! Magazine (reprinted according to terms of Creative Commons)

When Paola Gonzalez received a phone call from RIP Medical Debt, she was certain what she heard was a mistake. A prank, maybe. The caller said a $950 hospital bill had been paid for in full: It would not affect her credit and she wouldn’t have to worry about it again. “They wanted to pay a bill for me,” she said. “I was just speechless.”

The 24-year-old student from Roselle Park, New Jersey, has lupus, a chronic autoimmune disease that in 2011 put her in and out of hospitals for a year. Even with insurance she faces a barrage of medical bills that often get pushed aside. “I can’t always work,” Gonzalez said. “I’ll be fine today and sick tomorrow. It’s really amazing that people would help out like this.”

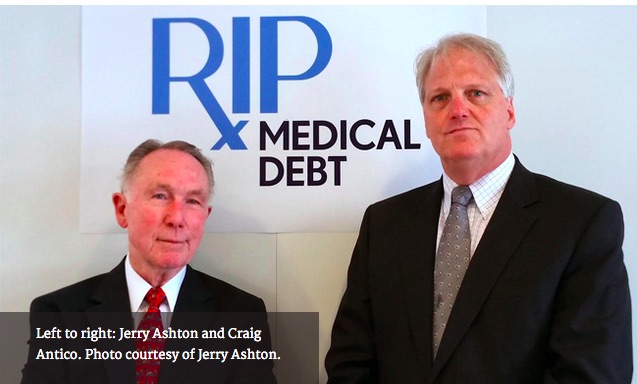

Gonzalez is one of many people who have had a debt paid by RIP Medical Debt, a nonprofit founded by two former debt collectors, Jerry Ashton and Craig Antico, that buys debt on the open market and then abolishes it, no strings attached. In the year since RIP Medical Debt started, the group has abolished just under $400,000, according to Antico. On July 4, it launched a year-long campaign to raise $177,600 in donations, which it will use to abolish $17.6 million of other people’s debt.

Millions of people are, in Ashton’s words, “sitting at the kitchen table and you have to decide, ‘Do I buy medication today or do I pay the water bill or do I pay the debt collector?’… We decided we should take the debt collector out of the equation.”

It works like this: typical collection agencies will buy debts from private practices, hospitals, and other collection agencies that don’t find it worthwhile to pursue the debt themselves. The buyers often get a steal, buying a debt for pennies on the dollar while charging the debtor the full amount, plus additional fees.

According to a 2013 report from the Federal Trade Commission, from 2006-2009 the nine biggest debt collection companies purchased about $143 billion of consumer debt for less than $6.5 billion; 17 percent of it was medical.

Antico and Ashton are plugged into the same marketplace. They say that with the money they raise, they buy the debt for around one percent of the amount it’s worth (when debtors settle directly with collection agencies, they pay an average of 60 percent of the loan.) Then, they forgive it.

Some debt-sellers find the cash in hand more valuable. Some doctors want the debt forgiven to help maintain a relationship with their patients.

Ashton worked in the debt collections business for more than 30 years. As he learned about its tactics, he was moved to start his own consulting firm with the goal of keeping people out of collections. He said the industry treated debts as “commodities” and sold them for a profit while the debtor struggled to pay off the full amount. “That I find to be unconscionable,” says Ashton.

(Article continued in the right side of the page)

(Article continued from the left side of the page)

He was inspired to rethink debt by the Occupy Wall Street movement and its offshoot, Strike Debt, which started the Rolling Jubilee, a program that began buying debt and abolishing it in October 2012.

Medical debt contributed to almost 60 percent of the bankruptcies in the United States in 2013. So when Rolling Jubilee shifted its focus to student loans, Ashton and Antico decided to pick up the torch.

“You don’t wake up one morning and decide to have a $150,000 mastectomy,” says Ashton. “This is not elective debt.”

For people with chronic illness, like Gonzalez, or those who require extended care, the prospect of a growing pile of debts that cannot be paid is simply frightening. For many, it leads to neglect of care they need: an estimated 25 million adults will not take medicine as prescribed because they cannot afford it; others will avoid the doctor altogether.

This is why RIP Medical debt sees the outstanding bills not just as unpaid, but ultimately unpayable. When buying debts, Ashton and Antico seek out patients whose payments create an immense burden—patients who either earn twice below the national poverty level or whose payments would require five percent or more of their income. They work with the hospitals and medical practices when purchasing debt portfolios to identify debtors who need aid the most.

Many of the people who need aid are not properly identified when they go through a hospital registration process. According to Antico, typically 5-10 percent of all hospital cases are uncompensated. When those who cannot pay are billed, those bills often turn into unpaid debts. “This is a systemic issue. It’s not their fault they got sick and incurred debt,” says Antico. “You can’t imagine how bad they feel and they shouldn’t have to.”

Crowd-funding for debt relief is becoming an increasingly popular trend. Back in 2002, a church in Virginia got together to eliminate its members credit card debts. Rolling Jubilee has abolished nearly $32 million in loans since it began. A UK man even tried to crowd-fund a bailout for Greece, raising almost €2 million from strangers by pointing out that Greece’s €1.6 billion debt simmers down to €3 from every European.

RIP Medical Debt has been criticized by some within the debt abolition movement for structuring itself as a nonprofit organization that pays for work (though Ashton and Antico work as volunteers, they pay outside contractors for things like website maintenance and design); whereas the above efforts and the original Rolling Jubilee focused entirely on grassroots organization and mutual aid.

Still, Ashton and Antico see potential for the project as an opportunity people to help their community. “I think everybody giving to everybody is how we should approach this,” Antico says.

As for Gonzalez, while she is excited and grateful for the bill that was paid, her ongoing condition means she still has a lot of debt to get through. Right now she’s focused on avoiding bankruptcy and managing the bill from her primary doctor while the others are pushed to the side. “I just hope that eventually I’ll be able to pay it off,” she said. “This is the first time I’ve been healthy for a couple months straight so I hope that it stays that way.”

(Thank you to Janet Hudgins, the CPNN reporter for this article.)