DISARMAMENT & SECURITY .

An article from NHK World

Atomic bomb survivors are getting older and their number is dwindling. An American NGO has come up with a new way of preserving their experiences. It’s calling global educators to Hiroshima and Nagasaki to discuss how to share the survivors’ messages with their students.

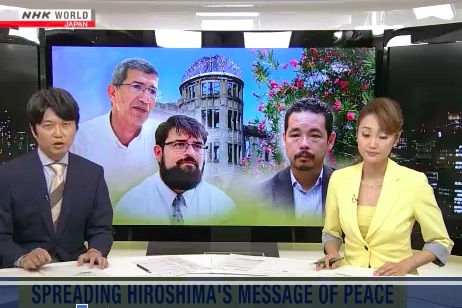

Frame from NHK video

In early August, a group of teachers from around the world gathered in the peace park.

“My first impression of the site was… It’s hard to look at for too long for me,” says Matthew Winters, one of the participants. He is a junior high school teacher from the US state of Utah.

“There is a narrative in the United States about Nagasaki and Hiroshima in which you enunciated very well about, it was necessary to drop the nuclear bomb. It was necessary to end the war,” he says.

Winters has held classes discussing whether the bombing was necessary. But he says he wasn’t sure what the right answer was. He came to Hiroshima to learn more. “There is a human factor there that goes well beyond what’s happening in the pages of a history book,” he says.

Another participant is Hacene Benmechiche from Algeria. He is a history lecturer, and believes that peace education is especially important in his region and the Middle East, where violence persists.

“So I want our students to be peace-loving children. We are weary of violence. Violence is not a good thing. It beats development, it shatters countries, it destroys families,” he says.

This program, “Oleander Initiative,” is named after the city flower of Hiroshima, the first one to bloom after the bombing. It has become a symbol of resilience and peace. The organizer, Ray Matsumiya, hopes the teachers and their students take home the spirit of Hiroshima. He learned about the horror of the bombing from his grandfather, who experienced it.

“With the nuclear weapons ban treaty, one of the ideas is to mobilize civil societies around the world. In terms of our program, it helps spread that knowledge of why nuclear weapons shouldn’t exist,” he says.

On this day, the participants visited an atomic bomb survivor. 88-year-old Teruko Ueno welcomed them for lunch. Ueno was 1.6 kilometers away from ground zero when the bomb was dropped.

She was 16 years old and worked as a nurse at the Red Cross Hospital. She was shielded from the extreme heat by the hospital building. She still suffers from the effects of the radiation.

(Continued in right column)

Can we abolish all nuclear weapons?

(Continued from left column)

After the bombing, she struggled for days to save her colleagues and patients, who were badly burned. “Their skin was melted off their bodies. People came to my hospital saying ‘Give me water,’ and collapsed,” she explains.

She recalls how many children were born with physical disabilities. Her daughter and granddaughter listen next to her. “People were saying we would give birth to children with deformities. I was so worried,” says Ueno.

The participants are at a loss for words. “Your story…Thank you, thank you, thank you…” Winters says to Ueno.

“I am glad to hear that,” Ueno responds.

“She gave me a giant hug that just made me cry immediately. It was like being hugged by my grandmother. It was so emotionally fulfilling. It changed me. I feel like a different person today than I did yesterday,” says Winters.

Benmechiche says he learned something different. “I cannot feel exactly the way they feel. But I think that they are ready to forgive, otherwise there are still very deep wounds inside, because they know that forgiveness, not forgetfulness,” he says.

The teachers were deeply impressed with the openness and resilience of the people of Hiroshima.

The ceremony this summer was particularly special for the people of Hiroshima. It marked the achievement of a long-standing goal — the nuclear weapons ban treaty adopted in July. The teachers took part in the events.

The teachers discussed the goal of a nuclear-free world and how countries can work together to attain it. They talked about the recent nuclear weapons ban treaty, and the deep rift between nuclear powers and non-nuclear states.

“It was almost like a virtual media blackout. There was nothing said about it, even though it happened at the UN in New York,” says Kathleen Sullivan, a lecturer from the US.

“Nothing would make any change. The gap will be there unless we do something with the leaders, with the politicians,” says Khalil Smidi, a teacher from Lebanon.

“That’s where the educator’s roles are so important. It was the people that brought the ban treaty. I mean the thing that was so exciting about it, was that it was actually a process of education,” responds Sullivan.

Winters shared his new determination with his peers.

“A large majority of my students have parents that work at that military base. They are air force people and it’s a large economic center for the city. So, to combat that is going to be very difficult. We have to start a dialogue about these issues,” he says.

The teachers come up with a motto: “Education is the best weapon.” They want their students to think about how they can make even a small amount of change toward a better world.

(Thank you to the Global Campaign for Peace Education for calling this article to our attention.)