TOLERANCE AND SOLIDARITY .

An article by Kumar Ramakrishna, Eurasia Review (Reprinted by permission)

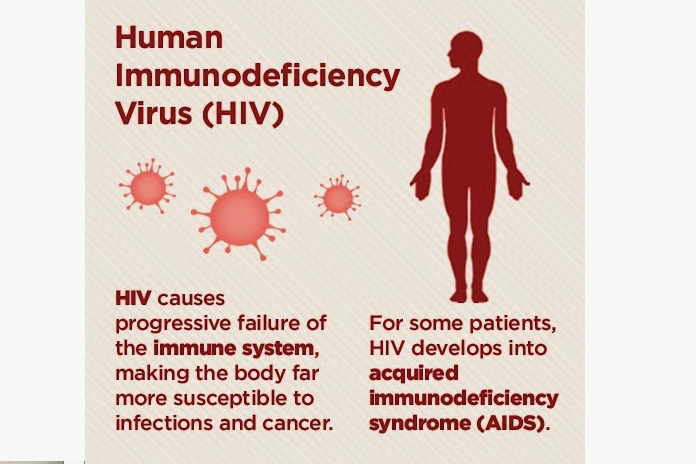

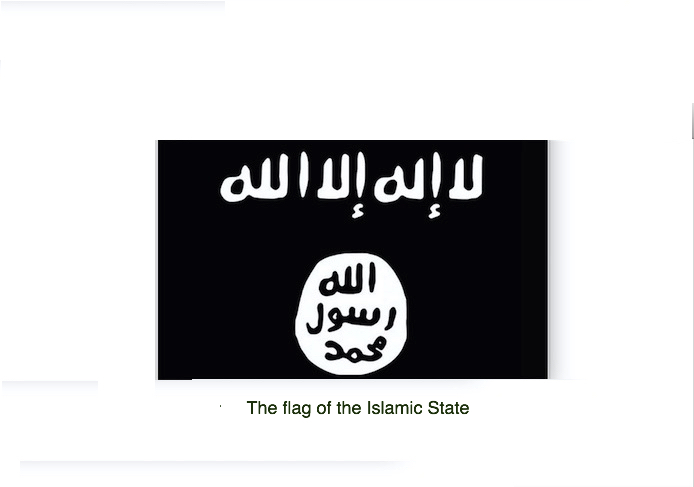

International concern at the rapidly metastasising global threat of the brutal Al Qaeda “mutation” known as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), has generated concerted discussions on effective strategies to counter its highly virulent ideology that has been widely disseminated through the Internet.

High-level summits on countering violent extremism (CVE) were held in Washington and in Sydney in the first half of this year, while more recently British Prime Minister David Cameron unveiled the United Kingdom’s new multi-faceted CVE strategy as well. In Southeast Asia, one potentially powerful idea – moderation – has been promoted as a means of neutralising the extremist appeal of ISIS.

The Global Movement of Moderates

First mentioned by Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak at the UN General Assembly in September 2010, the concept of moderation gained traction at the 18th ASEAN Summit in Jakarta in 2011 when ASEAN leaders endorsed the initiative to establish the Global Movement of Moderates to help shape global developments, peace and security. Subsequently the ASEAN Concept Paper on the Global Movement of Moderates (GMM) was adopted at the 20th ASEAN Summit in Phnom Penh, Cambodia in 2012.

Most recently, at the 26th ASEAN Summit in Langkawi, Malaysia on 27 April 2015, ASEAN leaders reiterated in the so-called Langkawi Declaration that the GMM initiative promotes a culture of peace and complements other initiatives, including the United Nations Alliance of Civilisations. The GMM Concept Paper recommended establishing dedicated ASEAN units to coordinate and evaluate all GMM-related activities within ASEAN and globally.

The Langkawi Declaration Programme

The Langkawi Declaration identifies several clusters of functional activities to promote the moderation norm, via collaboration between the GMM, the ASEAN Foundation and the ASEAN Institute of Peace and Reconciliation. The first cluster of activities includes organising outreach programmes, interfaith and cross-cultural dialogues at the national, regional and international levels. The second cluster involves the convening of forums to share best practices in understanding and countering violent extremist ideologies. An example is the East Asia Summit Symposium on Religious Rehabilitation and Social Reintegration held in Singapore in April 2015.

A third cluster encourages enhanced information-sharing on best practices in promoting moderation among ASEAN member states. A fourth cluster involves creating mechanisms to cultivate emerging leadership especially amongst women and youth that can help invigorate ASEAN’s drive and innovation in effectively addressing CVE issues as well as other global challenges. Importantly, a fifth cluster recognises education as an effective means of socialising the moderation norm and associated values such as respect for life, diversity and mutual understanding; this is a means of preventing the spread of violent extremism whilst addressing its root causes.

(article continued on the right side of the page)

Question for this article

Islamic extremism, how should it be opposed?

Readers’ comments are invited on this question and article. See below for comments box.

(article continued from the left side of the page)

Another cluster seeks to foster formal scholarly exchanges to amplify the collective voices of moderate intellectuals, while a seventh recognises the need for exchanging ideas with extra-regional dialogue partners, international organisations and other relevant stakeholders on successful case studies of engagement and integration policies that support moderation.

“God is in the Details”: Operationalising moderation

While this multifaceted plan of action by the GMM to promote the norm of moderation as a means of countering the violent extremism is commendable, as an ancient saying goes, “God is in the details”. A roundtable held in Singapore on 29 July 2015 identified several issues that need to be addressed for moderation to be effectively operationalised at the grassroots level, where the “immunisation” of vulnerable Southeast Asian Muslim constituencies against the digitised, apocalyptic-tinged Salafi Jihadism of ISIS is most needed.

But first, what exactly is “moderation” anyway?

Within Islam – from whose intellectual and theological resources a sustained counter-narrative campaign against ISIS must be fashioned – the idea of wasatiyah or the “Middle Way” of a “just and balanced community” seems to be one possible elucidation of the moderation norm. In this sense a true Muslim embodying wasatiyah effectively preserves his religious integrity whilst embracing tolerance toward both co-religionists of differing convictions on certain matters, as well as members of other – or even no – faiths.

Importantly, operationalising moderation must also involve developing clearer legal principles for regulating the ISIS penchant for takfir or excommunication of other groups – a habit that has all too frequently religiously legitimised their subsequent acts of extermination in grisly fashion.

Operationalising moderation further implies that Southeast Asian Muslims should be wary of uncritical acceptance of certain puritanical strains of the faith emanating from the Middle East. It has been suggested that Southeast Asian Islam – famously, Islam with a “smiling face” – is “lived Islam” which possesses ample religious authenticity vis-a-vis the imagined, virulently re-interpreted “desert Islam” of ISIS.

It is hence timely that in early August 2015 the two largest Islamic groups in Indonesia, Muhammadiyah and Nahdlatul Ulama – boasting 90 million members between them – affirmed their desire to promote a “progressive” Islam and more tellingly, an “Islam Nusantara” or “Islam of the archipelago” and that these ideas will be promoted in cyberspace as well.

Moderation is not for Muslims only

Finally, it should be recognised that the norm of moderation is not just an issue for the Muslim community alone. ISIS aside, Southeast Asia and the world has witnessed violent extremism of other religious and ethnic stripes as well. Hence within Southeast Asia at least, encouraging broader participation in further “ASEANising” the moderation concept so that is applies beyond regional Muslim constituencies would also help ensure it gets embedded in the socio-cultural and political DNA of the nascent ASEAN Community.

Ultimately, how would we know if the GMM initiative has succeeded? One clue would be when a Southeast Asian – although it is his right of “free expression” – voluntarily decides not to say or publish anything that might hurt the religious sentiments of a fellow Southeast Asian of another faith. Ancient religious texts summarise this as the principle of “not stumbling my brother”. Hence, rather than cynical self-censorship, what really lies at the heart of genuine moderation is quite simply, charity. Once Southeast Asians and others imbibe this idea, the days of ISIS and its ilk would surely be numbered.