. HUMAN RIGHTS .

An article by Neena Bhandari from InDepth News

More investment is needed in human rights education and strengthening of civil society to address inequality and sustainability – the main objectives of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. This was the key message from the Ninth International Conference on Human Rights Education (ICHRE) held in Sydney, Australia.

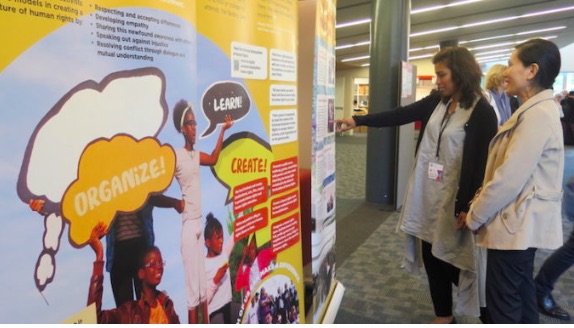

A glimpse of the exhibition on human rights education. (Photo credit: NGO Working Group on Human Rights Education and Learning)

Drawing inspiration from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), which marks its 70th Anniversary this year, the ICHRE 2018 (November 26-29) recommended all stakeholders to mainstream human rights education as a tool for social cohesion towards peaceful coexistence; and strive to bridge the significant gap between integrating human rights education in the curricula and its implementation.

“Beyond human rights education, people have to be enabled and empowered to exercise their inalienable rights, to live by those rights, and to uphold their rights and the rights of others,” said Dr Mmantsetsa Marope, Director of UNESCO’s International Bureau of Education, in her opening address.

She highlighted: “Three core factors – good governance, good health, and quality and relevant education – converge to enable and empower people to create and live a culture of human rights. These three factors are paramount, because they determine other factors that can facilitate or impede the realization of human rights.”

The sixth consultation of the implementation of UNESCO’s 1974 Recommendation in 2016 reported that more effort was required to strengthening teachers’ capacity to implement human rights education.

Equitas – International Centre for Human Rights Education, which provides tools and training to teachers and people working with children to integrate human rights values and approaches in the work that they do, reaches out to 100,000 young people across 50 communities in Canada each year.

Equitas Executive Director Ian Hamilton told IDN, “Currently our programme is focused on helping to educate primary school children aged between 6 and 12 years and adolescent youth between 13 and 18 years.

“Through our program, Play It Fair we use a series of games and activities to introduce human rights to children and encourage them to think critically about what is happening around them and how they can promote human rights values – equality, respect, inclusion and exclusion.

“For example, we ask children to play musical chairs the traditional way and then play a cooperative version and use that as an entry point to talk about inclusion and exclusion.”

Hamilton added: “We have seen that these tools also transform the people, who are working with children. They learn the content about the same time as the children, but it also makes them feel empowered, being equipped to deal with these issues.”

Equitas also works with young adults using similar participatory approaches and results, and through its virtual forum: speakingrights.ca.

Youth is the focus of the fourth phase (2020-2024) of the UN World Programme for Human Rights Education launched in September 2018.

Elisa Gazzotti, Programme Coordinator and Co-chair NGO Working Group on Human Rights Education and Learning, Soka Gakkai International Office for UN Affairs in Geneva, told IDN, “We use the technique of storytelling to engage young people to share how through human rights education they were able to steer their lives in a positive direction and become fully engaged actors in their communities.”

“We organised a workshop here around Transforming Lives – the power of human rights education exhibition, which was co-organised by SGI together with global coalition for human rights education HRE2020, the NGO Working Group on Human Rights Education and Learning and others in 2017 to celebrate the fifth anniversary of the adoption of the UN Declaration on Human Rights Education and Training. It shows how human rights education has transformed the lives of people in Burkina Faso, Peru, Portugal, Turkey and Australia,” Gazzotti added.

(Article continued in right column)

How can we promote a human rights, peace based education?

(Article continued from left column)

Arash Bordbar, a third-year engineering student at the Western Sydney University and Chair of the UNHCR Global Youth Advisory Council had fled Iran at the age of 15 years and stayed in Malaysia for five years before being resettled in Australia in 2015. He is now a youth worker at the Community Migrant Resource Centre, where he is supporting newly arrived migrants get education and find employment.

Similarly Apajok Biar, 23, who was born in Kakuma Refugee Camp in Kenya and came to Australia in 1997 with her family under a Humanitarian visa, is chairperson and co-founder of South Sudan Voices of Salvation Inc, a not-for-profit youth run and led organisation. As youth participation officer at Cumberland Council in Sydney, she has been working to ensure that young people from all backgrounds have the opportunity to have a say in decisions that affect them at all levels – local, state, international.

“Knowledge of these rights can both improve relations between people of different ethnicity and belief, and nourish civil society,” said Dr Sev Ozdowski, Conference Convener and Director of Equity and Diversity at Western Sydney University.

Over 300 representatives from international human rights organisations, civil society, educational institutions, media and citizens participated in the ICHRE 2018, a series initiated by Dr Sev Ozdowski, to advance human rights education for the role it plays in furthering democracy, the rule of law, social harmony and justice.

While UDHR has been reinforced by several legal instruments, including conventions, charters, declarations, and national legislation, and the global discourse has broadened to include gender equality, people living with disabilities and LGBTIQ communities, the biggest challenge is the threat facing human rights organisations and defenders.

“That is the most dangerous threat because if we silence those voices then our capacity to educate and mobilise the public reduces and we will end up excluding most people,” Equitas Executive Director Hamilton told IDN.

In many countries, human rights are still not a priority. Tsering Tsomo, Executive Director of Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy, an NGO based in Dharamsala (India) said: “In Tibet, the Chinese authoritarian regime has criminalised the UDHR itself by punishing people who translated the UDHR in Tibetan language and disseminated it amongst Tibetans.

“This happened in 1989 when 10 Tibetan monks were sent to jail for propagating the UDHR, just a year after the Chinese government publicly acknowledged the existence of Human Rights Day. Along with celebrating the 70th anniversary, we also observe the 30th anniversary of the imprisonment of the 10 Tibetan monks.”

UDHR holds the Guinness Book World Record as the most translated document. It is now available in more than 500 languages and dialects.

“In Tibet, there is a lot of rhetoric about human rights, but no implementation. Instead there is total impunity for the crimes committed by security forces and an upsurge in government spending on domestic security, which has long surpassed defence spending. This has resulted in a series of human rights violations.

“The challenge for the UN and human rights organisations is to counter the economic and political pressure exerted by powerful countries in reframing the international human rights discourse and in silencing critical civil society voices,” Tsomo told IDN.

Speaking on the path from UDHR to the World Programme for Human Rights Education, Cynthia Veliko, South-East Asia Regional Representative of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) in Bangkok said: “The shocking retrenchment in leadership on human rights in many States across the globe over the past few years poses a real threat to the historic progress made, often painstakingly, over the decades that followed the 1948 adoption of the UDHR.”

“The continued realisation of the principles set out in the UDHR ultimately cannot be achieved without human rights education. It is an essential investment that is required to shape future world leaders with the principles of humanity and integrity that are required to build and sustain a humane world,” Veliko added.

The ICHRE 2018 Declaration also raised concerns on the human rights implications of insufficient progress in climate change mitigation and adaptation, increasing food and water insecurity, rising sea levels, inter-state and internal conflict leading to increased migration, escalating new arms race among major powers, and rising levels of violence – particularly violence against women and children.

The Declaration called for greater awareness of the opportunities and risks of new forms of communication and media opportunities, which will help engage and reach more children and young adults, but also pose the threat of human rights abuse online.

(Thank you to the Global Campaign for Peace Education for calling our attention to this article.)