|

|

Egypt’s revolution vindicates Gene Sharp’s theory of nonviolent activism

un articulo por John Horgan, Scientific American (abridged)

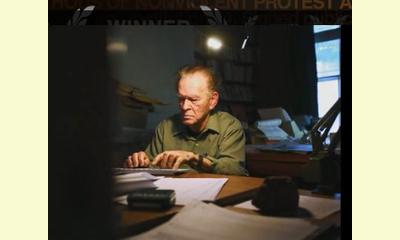

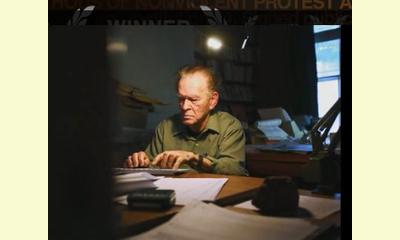

Video: Gene Sharp: How to Start a Revolution

The nonviolent uprising . . . in Egypt represents an extraordinary vindication of the philosophy of Gene Sharp, a political scientist whose work I described here last July. For decades, Sharp has argued that nonviolence is the best means of overthrowing corrupt, violent, repressive regimes. He disseminates his ideas through books such as From Dictatorship to Democracy: A Conceptual Framework for Liberation (1993), which has been translated into 24 languages, including Arabic, and can be downloaded from the Web site of The Albert Einstein Institution, a tiny nonprofit founded by Sharp in 1983.

click on photo to enlarge

Sharp is not a moralist but a pragmatist, who bases his claims on an empirical analysis of history. He asserts that violence, even in the service of a just cause, often results in more problems than it solves, leading in turn to greater injustice and suffering; hence, the best way to oppose an unjust regime is through nonviolent action. Nonviolent movements are also more likely than violent ones to garner internal and international support and to lead to democratic, non-militarized regimes.

Nonviolent resistance, Sharp acknowledges, requires enormous dedication, courage and hard work, all of which may culminate in failure, including the death of resistors. But nonviolent resistance has played a much more significant role in human history than generally acknowledged by historians. "Using nonviolent action, people have won higher wages, broken social barriers, changed government policies, frustrated invaders, paralyzed an empire and dissolved dictatorships," Sharp wrote. . .

Nonviolent resistance even worked in Nazi-occupied Norway. In 1942, Norway’s puppet leader Vidkun Quisling ordered teachers to join a "corporation" that would promote fascist principles. As many as 10,000 of Norway’s 12,000 teachers refused to join the organization and signed statements of protest. Quisling had 1,000 teachers arrested and sent to concentration camps, but the others maintained their resistance. Quisling finally gave in, allowing the imprisoned teachers to return home.

The necessary first step toward changing an unjust regime, Sharp emphasizes, is for people to reject the self-fulfilling view of themselves as weak; after all, even the most brutal tyrants must rely to some extent on the cooperation of citizens, not just in the military but throughout the society. Sharp is not the first scholar to offer this insight. . .

Asking how 30,000 Englishmen "subdued" 200 million Indians, Tolstoy responded: "Do not the figures make it clear that it is not the English who have enslaved the Indians, but the Indians who have enslaved themselves?" Gandhi, Sharp’s most important influence, said his campaigns against British rule required convincing his fellows Indians to "consider it a shame to assist or cooperate with a government that had forfeited all title to respect or support."

Millions of Egyptians apparently reached a similar conclusion about the Mubarak regime. Even Sharp seemed taken aback by the success of the Egyptian uprising. "I would not have predicted this," he told the Catholic National Reporter 10 days before Mubarak’s resignation. Sharp said the Egyptian revolution may be "the most powerful example of ‘people power’… in world history." May Egypt—and the writings of Gene Sharp—help other people fighting injustice recognize the power of nonviolence.

|

|

DISCUSSION

Pregunta(s) relacionada(s) al artículo :

Does research show that nonviolence works?,

* * * * *

Comentario más reciente:

:

Did the writings on nonviolence by Gene Sharp help inspire the movements of the Arab Spring in Egypt and elsewhere?

This is debatable. The New York Times said "yes" and some Egyptians, for example, the blogger Karim Alrawi say "no".

However, it should be recognized that the ideas of nonviolent resistance have a way of transcending borders and centuries. Nelson Mandela was influenced by Martin Luther King who was influenced in turn by Mahatma Gandhi who was influenced in turn by Henry David Thoreau.

[Note added later: The blog of Karim Alrawi is no longer available on the Internet, but see instead the blog of Hossam El-Hamalawy who says that the Palestinians "have been the major source of inspiration, not Gene Sharp, whose name I first heard in my life only in February after we toppled Mubarak already and whom the clueless NYT moronically gives credit for our uprising."

|

|