|

|

Human Rights Watch Annual Report: Rights Struggles of 2013

un articulo por Kenneth Roth, Executive Director, Human Rights Watch (abridged)

Video: Human Rights Watch annual report

Looking back at human rights developments in 2013,

several themes stand out. The unchecked slaughter

of civilians in Syria elicited global horror and

outrage, but not enough to convince world leaders

to exert the pressure needed to stop it. That has

led some to lament the demise of the much-vaunted

“Responsibility to Protect” doctrine, which world

governments adopted less than a decade ago to

protect people facing mass atrocities. Yet it

turned out to be too soon to draft the epitaph for

R2P, as it is known, because toward the end of the

year it showed renewed vitality in several African

countries facing the threat of large-scale

atrocities: Central African Republic, South Sudan,

and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

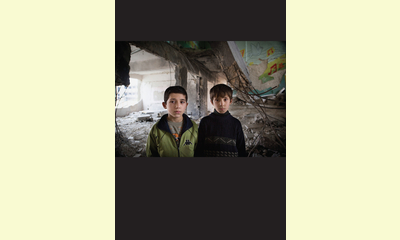

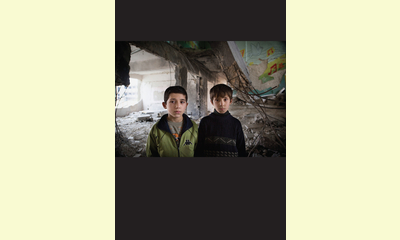

Two boys stand in a school building damaged by government shelling in Aleppo, Syria, February 2013. © 2013 Nish Nalbandian/Redux

click on photo to enlarge

Democracy took a battering in several countries,

but not because those in power openly abandoned

it. Many leaders still feel great pressure to pay

lip service to democratic rule. But a number of

relatively new governments, including in Egypt and

Burma, settled for the most superficial forms—only

elections, or their own divining of majoritarian

preferences—without regard to the limits on

majorities that are essential to any real

democracy. This abusive majoritarianism lay behind

governmental efforts to suppress peaceful dissent,

restrict minorities, and enforce narrow visions of

cultural propriety. Yet in none of these cases did

the public take this abuse of democracy sitting

down.

Since September 11, 2001, efforts to combat

terrorism have also spawned human rights abuses.

The past year saw intensified public discussion

about two particular counterterrorism programs

used by the United States: global mass electronic

surveillance and targeted killings by aerial

drones. For years, Washington had avoided giving

clear legal justifications for these programs by

hiding behind the asserted needs of secrecy. That

strategy was undermined by whistleblower Edward

Snowden’s revelations about the surveillance

program, as well as by on-the-ground reporting of

civilian casualties in the targeted-killing

program. Both now face intense public scrutiny.

In the midst of all this upheaval, there were also

important advances in the international machinery

that helps to defend human rights. After a slow

and disappointing start, the United Nations Human

Rights Council seemed to come onto its own, most

recently with significant pressure applied to

North Korea and Sri Lanka. And two new

multinational treaties give hope for some of the

world’s most marginalized people: domestic workers

and artisanal miners poisoned by the unregulated

use of mercury.

In 2005, the world’s governments made an historic

pledge that if a national government failed to

stop mass atrocities, they would step in. The

international community has since invoked the R2P

doctrine successfully to spare lives, most notably

in Kenya in 2007-2008 and Côte d’Ivoire in 2011.

However, many governments criticized the doctrine

after NATO’s 2011 military intervention in Libya,

where NATO was widely perceived to have moved

beyond the protection of civilians to regime

change. The reaction poisoned the global debate

about how to respond to mass atrocities in Syria.

The utter failure to stop the slaughter of Syrian

civilians has raised concerns that the doctrine is

now unraveling. Yet that damning shortcoming

should not obscure several cases [mentioned above]

in 2013 in which R2P showed considerable vibrancy.

. .

( Click here for a version in Spanish or here for a version in French.)

|

|

DISCUSSION

Pregunta(s) relacionada(s) al artículo :

What is the state of human rights in the world today?,

* * * * *

Comentario más reciente:

:

Each year we get overviews of the state of human rights in the world from Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch.

|

|