|

|

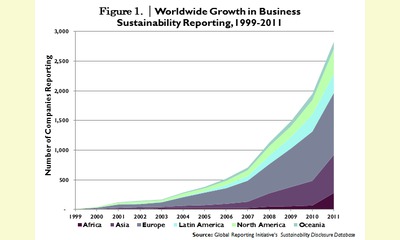

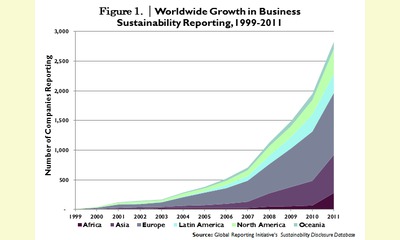

More Businesses Pursue Triple Bottom Line for a Sustainable Economy

un articulo por Colleen Cordes, Worldwatch Institute (abridged)

As corporations of all sizes increasingly choose

to monitor and report on their social and

environmental impacts, a growing number of mostly

small and medium-sized companies are going even

further: They are volunteering to be held publicly

accountable to a new triple bottom line—

prioritizing people and the planet as well as

profits.

Source: Global Reporting Initiative's Sustainably Disclosure Database

click on photo to enlarge

Just how broadly, rapidly, and rigorously this

movement can spread is of critical importance,

given the supersized global impacts of for-profit

enterprises. Sustainable economies are likely to

remain elusive without substantial shifts in

corporate norms. As I point out in “More

Businesses Pursue Triple Bottom Line for a

Sustainable Economy,” the latest Vital

Signs Online study, recent data provide signs

that such change is possible and indeed may even

have begun.

Over the last 15 years, for example, the number of

businesses of all sizes that choose to self-assess

how sustainable their operations are, using widely

accepted social and environmental standards, and

to publicly disclose their results has been

growing rapidly, especially in Europe and Asia.

Recently there also has been a rise of a fast-

moving movement, with significant leadership

provided by sustainably minded businesses, whose

goal is to persuade lawmakers to create a new

legal status known as “benefit corporation” that

for-profit businesses can choose voluntarily. The

movement for benefit corporation statutes began in

the United States, under the leadership of B Lab,

which developed model legislation with the pro

bono help of U.S. law firms.

A “benefit corporation” is a corporate form that

requires a company to legally establish in its

original or amended articles of incorporation that

it has a general purpose of having a positive impact

on society and the environment . . .

Proponents of this new corporate form say it

essentially bakes a triple bottom line into a

company’s DNA that frees companies from the fear

of shareholder lawsuits if their decisions fail to

maximize shareholder value because of some

competing interest of other stakeholders, such as

workers. Under current corporate case law in the

United States, for example, corporate directors

are generally assumed to be liable in such suits.

Incorporation as a benefit corporation is intended

to establish the directors’ fiduciary

responsibility to consider the interests of all

stakeholders. Formalizing a company’s social and

environmental purposes under a legal framework

also makes it more likely that its good intentions

will survive the departure of its founders or any

major spurts of growth and that its directors will

have the legal backbone to fend off buyout offers

from conventional corporations that do not have

the same commitments.

Most benefit corporations to date are either small

or medium-sized businesses. But they include a few

larger companies that are privately held, such as

the outdoor apparel and accessory firm Patagonia

Inc., which reportedly had annual sales of about

$540 million for the year ending April 2012, and

King Arthur Flour, an employee-owned, 223-year-old

company with reported sales of about $84 million

in 2010. . .

|

|

DISCUSSION

Pregunta(s) relacionada(s) al artículo :

How can we get to a sustainable, peaceful economy?,

* * * * *

Comentario más reciente:

Annie Leonard: How to Be More than a Mindful Consumer

The way we make and use stuff is harming the world—and ourselves. To create a system that works, we can't just use our purchasing power. We must turn it into citizen power.

by Annie Leonard

posted Aug 22, 2013

Stuff activist Annie Leonard: “Consumerism, even when it tries to embrace ‘sustainable’ products, is a set of values that teaches us to define ourselves, communicate our identity, and seek meaning through accumulation of stuff, rather than through our values and activities and our community.” YES! photo by Lane Hartwell.

Since I released "The Story of Stuff" six years ago, the most frequent snarky remark I get from people trying to take me down a notch is about my own stuff: Don't you drive a car? What about your computer and your cellphone? What about your books? (To the last one, I answer that the book was printed on paper made from trash, not trees, but that doesn't stop them from smiling smugly at having exposed me as a materialistic hypocrite. Gotcha!)

Let me say it clearly: I'm neither for nor against stuff. I like stuff if it's well-made, honestly marketed, used for a long time, and at the end of its life recycled in a way that doesn't trash the planet, poison people, or exploit workers. Our stuff should not be artifacts of indulgence and disposability, like toys that are forgotten 15 minutes after the wrapping comes off, but things that are both practical and meaningful. British philosopher William Morris said it best: "Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful."

Too many T-shirts

The life cycle of a simple cotton T-shirt—worldwide, 4 billion are made, sold, and discarded each year—knits together a chain of seemingly intractable problems, from the elusive definition of sustainable agriculture to the greed and classism of fashion marketing.

The story of a T-shirt not only gives us insight into the complexity of our relationship with even the simplest stuff; it also demonstrates why consumer activism—boycotting or avoiding products that don’t meet our personal standards for sustainability and fairness—will never be enough to bring about real and lasting change. Like a vast Venn diagram covering the entire planet, the environmental and social impacts of cheap T-shirts overlap and intersect on many layers, making it impossible to fix one without addressing the others.

I confess that my T-shirt drawer is so full it's hard to close. . ... continuación.

|

|