|

|

UN: Landmark Arms Trade Treaty to become reality with 50th ratification

un article par Amnesty International (abridged)

Protection for the millions of people whose lives are devastated by

the poorly regulated global arms trade is set to take a giant leap

forward today, Amnesty International said with the historic Arms Trade Treaty

expected to surpass the 50 ratifications needed to trigger a 90-day

countdown to entry into force.

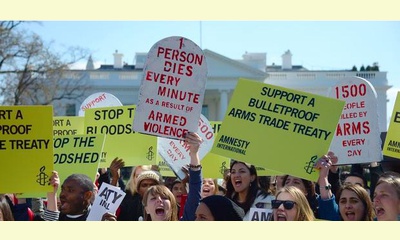

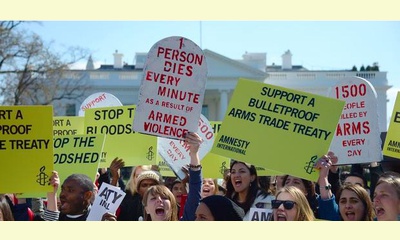

The global Arms Trade Treaty will soon become legally binding now that 50 states have ratified. © AFP/Getty Images

click on photo to enlarge

Argentina, the Bahamas, Czech Republic, Portugal, Saint Lucia,

Senegal and Uruguay are expected to be the latest states to confirm

ratification of the treaty at a ceremony at the UN in New York. The

ATT now looks set to become international law on 25 December

2014 binding all the countries that have ratified it by then.

“This is a milestone in the fight to end the human suffering caused

by the irresponsible flow of arms. By the end of this year, there will

be robust global rules to stop arms going to human rights abusers,”

said Salil Shetty, Secretary General of Amnesty International.

“This remarkable progress would not have been possible without

the support of more than a million people who helped keep up the

pressure on governments and said ‘enough is enough, the supply of

arms for atrocities and abuses must stop’. But the campaign does

not stop here, all states need to urgently bite the bullet and commit

to the Arms Trade Treaty.”

Amnesty International has lobbied and campaigned

relentlessly since the mid-1990s for an Arms Trade Treaty. At

least half a million people die every year on average and millions

more are injured, raped and forced to flee from their homes as a

result of the poorly regulated global trade in weapons.

The ATT includes a number of rules to stop the flow of weapons to

countries when it is known they would be used to commit or

facilitate genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes or other

serious violations of human rights.

Five of the top 10 arms exporters – France, Germany, Italy, Spain

and the UK have already ratified the ATT. While the USA is yet to

ratify it has signed the treaty. There has been resistance to

ratification from other major arms producers like China, Canada,

Israel and Russia. . . .

On 2 April 2013, a total of 155 states voted

in the UN General Assembly to adopt the ATT and 119 states

have since signed the treaty, indicating their willingness to bring it

into their national law. Although 41 states that supported the

adoption of the treaty last year have yet to sign the treaty,

international momentum to make the treaty a reality is still growing.

. . .

|

|

DISCUSSION

Question(s) liée(s) à cet article:

How did the arms treaty come about?, and who worked on it?

* * * * *

Commentaire le plus récent:

The following account comes from Amnesty International:

The long journey towards an Arms Trade Treaty

(click here for the treaty text).

Sometimes a simple but potentially revolutionary idea can change the world for the better.

But it often takes a crisis to galvanize people to take action.

This was the case two decades ago when the worldwide civil society movement – led by Amnesty International – took on the immense challenge of regulating the global trade in conventional arms.

For many world leaders, the 1991 Gulf War in Iraq drove home the dangers of an international arms trade lacking in adequate checks and balances.

When the dust settled after the conflict that ensued when Iraqi President Saddam Hussein’s powerful armed forces invaded neighbouring Kuwait, it was revealed that his country was awash with arms supplied by all five Permanent Members of the United Nations Security Council. Several of them, it emerged, had also armed Iran in the previous decade, fuelling an eight-year war with Iraq that resulted in hundreds of thousands of civilian deaths.

The crisis of legitimacy in the conventional arms trade triggered a paradigm shift, says Brian Wood, Amnesty International's Head of Arms Control and Human Rights. “It was big series of scandals at the time. The Permanent Five Security Council members and the other major players had no choice but to do something to regain confidence from world opinion.”

Transcending the old idea

Political leaders had already tried in vain in previous decades to rein in the poorly regulated global arms trade.

In 1919, horrified by the slaughter of the First World War, the newly formed League of Nations tried to restrict and reduce international arms transfers of the type that had led to death and destruction on a massive scale during the war.

But those efforts in the 1920s and 1930s to establish a treaty were variously designed on the basis of old colonial rivalries – and soon collapsed. Countries with empires and ambitions returned to massive re-arming through production and transfers, leading to another catastrophic global war that erupted in 1939.

In the wake of the Second World War’s atrocities and loss of life on a scale never before seen, the emerging international community established three pillars – the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the UN Charter, and the Geneva Conventions. These were a huge step forward for global human rights and humanitarian standards.

Like the League of Nations Covenant, the UN Charter had a mandate given to the Security Council to establish a system for the regulation of arms, but for more than 60 years the Security Council never even proposed a system for the conventional arms trade, despite the trade continuing to grow and fuel the very violations the three new global standards were meant to curtail.

Although the Cold War brought with it new multilateral controls over the movement of arms across borders, such limitations were outside the UN and part of the calculated global game of chess between NATO members on the one hand and Warsaw Pact countries on the other. Any concern for the human rights or humanitarian impact of arms transfers was again notably absent.

But a series of shocking crises in the late 1980s and 1990s – the first Gulf War, the Balkans conflicts, the 1994 Rwanda genocide and conflicts in Africa’s Great Lakes region, West Africa, Afghanistan and in Central America amongst others – drove home the urgency of moving forward with attempts to control the global arms trade.

The International Code of Conduct

As these crises were kicking off, NGOs and lawyers became increasingly concerned about the serious human rights and humanitarian impact of irresponsible arms transfers.

Wood recalls how in 1993 and 1994, he and representatives from three other NGOs met in an Amnesty International office in central London to draw up a draft legally binding International Code of Conduct for international arms transfers – for tactical reasons aimed initially at European Union (EU) member states.

The EU – shocked by the post-Gulf War revelations about transfers of weapons and munitions – had just agreed to a list of eight criteria for arms exports. This was followed by a set of principles on arms exports agreed in the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) in November 1993. . ... continuation.

|

|