|

|

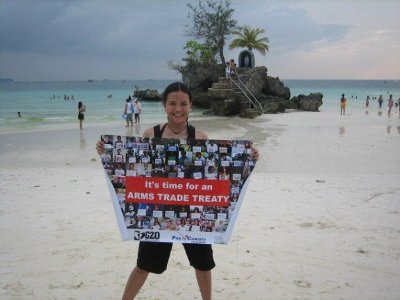

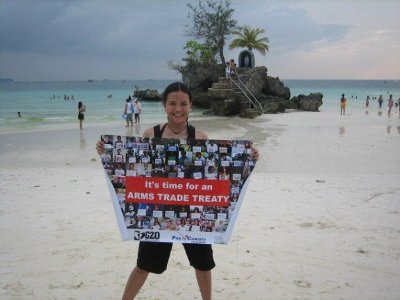

What the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) means to a young person like me…

un article par Meg Villanueva

As I walked on my way out of the United Nations

Headquarters in New York last April 2, 2013, I

could not help but keep the big smile (cheek to

cheek) on my face, my heart as if shouting “we did

it!” Yes, we did – we now have an Arms Trade

Treaty! Adopted by the UN General Assembly on that

same day!

click on photo to enlarge

40 minutes ago, I was sitting in the General

Assembly among a number of NGO/civil society

representatives, including the Control Arms

Campaign, a coalition which I am part of. My

heartbeat was pumping double time as I wait for

the results of the vote on the screen, where the

list of countries in green font was being

displayed. Then, it was announced, 154 voting YES,

23 ABSTAIN and 3 voting NO. The NGO side on the

4th floor/level burst into a long applause, and I

shouted “wooohoooo!”

Five days back, (Thursday, March 28, 2013), the

consensus process failed after Syria, the

Democratic People´s Republic of North Korea, and

the Islamic Repubic of Iran blocked the Arms Trade

Treaty agreement. Despite many attempts to save

the process through further consultation, the

President of the Conference, Ambassador Peter

Woolcott of Australia, reached a conclusion that

CONSENSUS could not be achieved.

At this exact moment of voting, I was sitting

right next to my father in Conference Room 1,

where all other campaigners and civil society

representatives who could not be accommodated in

the main meeting room were gathered. As we watched

fervently on the screen where a live video of the

adoption process (happening in the next room) was

being shown, I could feel the “sighs” and

frustration of campaigners and civil society

representatives from around the world.

At one point, after the floor was given for Syria

to speak (after North Korea and Iran) - the room

suddenly burst into some sort of “yeah right, this

must be a joke” laughter. The frustration I felt

towards the decision converted into a feeling of

being ganged-up on. I am from a small developing

country in Asia (Philippines). To think that three

(yes, 3!) countries can destroy/ruin an initiative

like the ATT, pushed by so many countries in the

world, seemed like an unbelievable mistake that we

have allowed our social structures to do to us. It

felt like my present and future (our present and

future!) was being dictated by these three

countries – and we are voiceless about it.

Reflection on the consensus process.

The consensus process, to me, does not give room

for diversity, for differences that we all have in

reality. To me it is a flawed decision making

process. Honestly, I believe that all other

processes that involve nation states to decide on

the “future” of its people, to me are also flawed

systems. We are all aware of the many

countries/nations that are not representative of

its people! And is there “real” democracy being

practiced by nations? I doubt.

(This article is continued in the discussionboard)

|

|

DISCUSSION

Question(s) liée(s) à cet article:

How did the arms treaty come about?, and who worked on it?

* * * * *

Commentaire le plus récent:

The following account comes from Amnesty International:

The long journey towards an Arms Trade Treaty

(click here for the treaty text).

Sometimes a simple but potentially revolutionary idea can change the world for the better.

But it often takes a crisis to galvanize people to take action.

This was the case two decades ago when the worldwide civil society movement – led by Amnesty International – took on the immense challenge of regulating the global trade in conventional arms.

For many world leaders, the 1991 Gulf War in Iraq drove home the dangers of an international arms trade lacking in adequate checks and balances.

When the dust settled after the conflict that ensued when Iraqi President Saddam Hussein’s powerful armed forces invaded neighbouring Kuwait, it was revealed that his country was awash with arms supplied by all five Permanent Members of the United Nations Security Council. Several of them, it emerged, had also armed Iran in the previous decade, fuelling an eight-year war with Iraq that resulted in hundreds of thousands of civilian deaths.

The crisis of legitimacy in the conventional arms trade triggered a paradigm shift, says Brian Wood, Amnesty International's Head of Arms Control and Human Rights. “It was big series of scandals at the time. The Permanent Five Security Council members and the other major players had no choice but to do something to regain confidence from world opinion.”

Transcending the old idea

Political leaders had already tried in vain in previous decades to rein in the poorly regulated global arms trade.

In 1919, horrified by the slaughter of the First World War, the newly formed League of Nations tried to restrict and reduce international arms transfers of the type that had led to death and destruction on a massive scale during the war.

But those efforts in the 1920s and 1930s to establish a treaty were variously designed on the basis of old colonial rivalries – and soon collapsed. Countries with empires and ambitions returned to massive re-arming through production and transfers, leading to another catastrophic global war that erupted in 1939.

In the wake of the Second World War’s atrocities and loss of life on a scale never before seen, the emerging international community established three pillars – the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the UN Charter, and the Geneva Conventions. These were a huge step forward for global human rights and humanitarian standards.

Like the League of Nations Covenant, the UN Charter had a mandate given to the Security Council to establish a system for the regulation of arms, but for more than 60 years the Security Council never even proposed a system for the conventional arms trade, despite the trade continuing to grow and fuel the very violations the three new global standards were meant to curtail.

Although the Cold War brought with it new multilateral controls over the movement of arms across borders, such limitations were outside the UN and part of the calculated global game of chess between NATO members on the one hand and Warsaw Pact countries on the other. Any concern for the human rights or humanitarian impact of arms transfers was again notably absent.

But a series of shocking crises in the late 1980s and 1990s – the first Gulf War, the Balkans conflicts, the 1994 Rwanda genocide and conflicts in Africa’s Great Lakes region, West Africa, Afghanistan and in Central America amongst others – drove home the urgency of moving forward with attempts to control the global arms trade.

The International Code of Conduct

As these crises were kicking off, NGOs and lawyers became increasingly concerned about the serious human rights and humanitarian impact of irresponsible arms transfers.

Wood recalls how in 1993 and 1994, he and representatives from three other NGOs met in an Amnesty International office in central London to draw up a draft legally binding International Code of Conduct for international arms transfers – for tactical reasons aimed initially at European Union (EU) member states.

The EU – shocked by the post-Gulf War revelations about transfers of weapons and munitions – had just agreed to a list of eight criteria for arms exports. This was followed by a set of principles on arms exports agreed in the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) in November 1993. . ... continuation.

|

|