|

|

In education, girls deserve what works

an article by Stephanie Psaki, Devex (abridged)

Ranging from viral celebrity videos by Alicia Keys or Susan

Sarandon to declarations of support from political leaders like

Michelle Obama or Graça Michel, there’s definitely a global

momentum for supporting girls’ education.

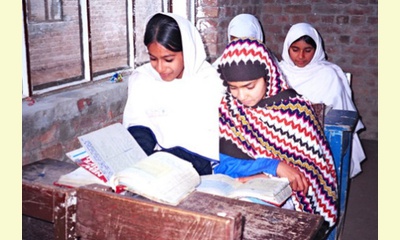

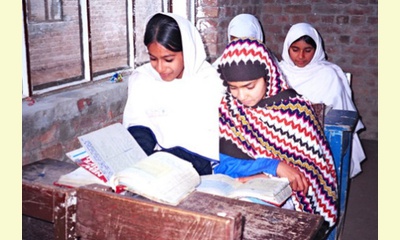

Council researchers studied the implications of changes in schooling opportunities in rural Pakistan and their implications for family building as well as children’s school participation and attainment. Photo by: Population Council

click on photo to enlarge

This widespread attention has led to greater recognition of the

importance of the issue, as well as the dividends it can reap.

Globally, girls who attend school during adolescence begin

having sex, marry and have children later, are less likely to get

HIV or have other reproductive health problems, engage in

fewer hours of domestic labor, and experience greater gender

equality.

Despite all these potential gains, 17 countries — 13 of them

in Africa — still have fewer than 90 girls enrolled in primary

school for every 100 boys. When girls (and boys) do attend

school, the quality of schooling in many settings is so poor

that they emerge without basic skills. Equally concerning,

preliminary evidence from the Population Council’s research in

Malawi shows that after leaving school, girls are significantly

more likely to lose both reading and numerical skills than

boys.

See more news on girls’ education:

● For Nigerian girls, education is the key that

opens doors to progress

● How to empower the girl

child

● It's time to unleash girls'

potential

More work is needed to translate schooling into lifelong

success for girls in developing countries. To date, very little

attention has been paid to investigating what kinds of

investments have an impact on girls — what specific programs

or actions are effective in keeping girls in school, helping

them learn, and empowering them to transition to healthy and

productive lives after leaving school.

In fact, research is so limited that, in a pivotal publication

about the state of girls’ education, Our researcher Cynthia

Lloyd found that girls’ education interventions fell into 12

main categories. Out of those, only two — hiring female

teachers and scholarships and cash transfers — had been

proven effective. The remaining ten approaches, while

promising, were not supported by evidence despite

widespread adoption.

We often hear the phrase, “We know what works; we just have

to do it.” And the value of insight and intuition gained through

work with girls and in their communities can’t be overstated.

But interventions that are popular and appear to have a

positive effect in the short-term, while often valuable for

other reasons, do not always have the impact we’re expecting

in the long-term. What works for one girl might not work for

all—or even most—girls. And what works in one location

might not work in another. . .

As this global movement evolves, donors and organizations

that work with and on behalf of girls should demand a higher

standard of evidence to guide our efforts. Investments should

be focused on programs that have been demonstrated to be

effective in achieving clearly stated goals, or on evaluating

promising interventions that lack sufficient evidence to date.

Girls around the world deserve no less.

[Thank you to Janet Hudgins, the CPNN reporter for this

article.]

|

|

DISCUSSION

Question(s) related to this article:

Gender equality in education, Is it advancing?

* * * * *

Latest reader comment:

Re: Gender equality in education: is it advancing

Considering that the first women to somehow get into universities was in the 19th C, we are making tortoise-like progress. Although there are more women than men in most schools now they tend toward the Arts where they are scorned by men in science. That's the kind of thing that was passed around 60 - 70 years ago but it's still here today. But, there is a trend that will make a difference quite soon: the majority of regional politicians are women who are Arts grads and they are going to shift the weight of policy to domestic from global. That will mean less war, more peace, more freedom and better education for women.

|

|