TOLERANCE & SOLIDARITY .

An article from Monthly Review Online (Reprinted according to Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License)

Sixty Israeli teenagers published an open letter addressed to top Israeli officials on Tuesday morning, in which they declared their refusal to serve in the army in protest of its policies of occupation and apartheid.

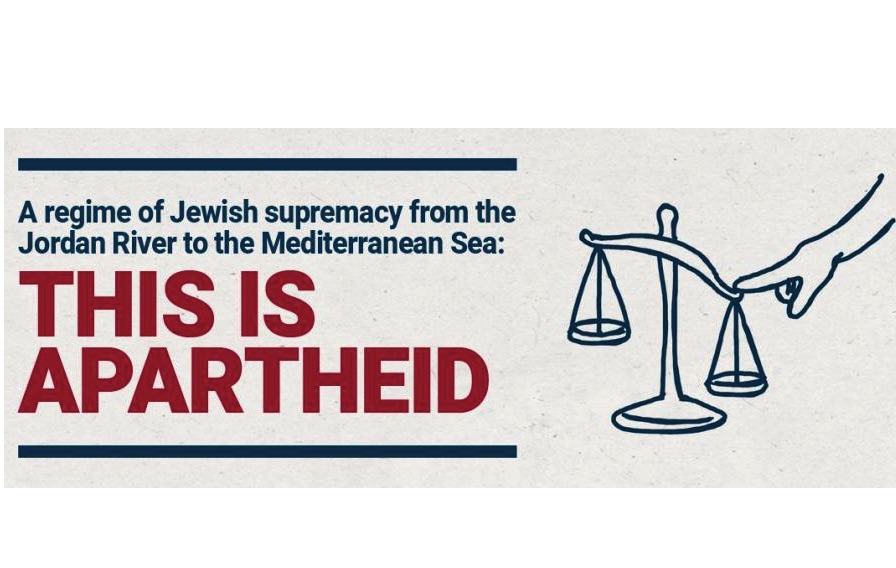

The so-called “Shministim Letter” (an initiative with the Hebrew nickname given to high school seniors) decries Israel’s military control of Palestinians in the occupied territories, referring to the regime in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and East Jerusalem as an “apartheid” system entailing “two different systems of law; one for for Palestinians and another for Jews.”

“It is our duty to oppose this destructive reality by uniting our struggles and refusing to serve these violent systems–chief among them the military,” reads the letter, which was addressed to Defense Minister Benny Gantz, Education Minister Yoav Galant, and IDF Chief of Staff Aviv Kochavi.

Our refusal to enlist to the military is not an act of turning our backs on Israeli society,” the letter continues.

On the contrary, our refusal is an act of taking responsibility over our actions and their repercussions. Enlistment, no less than refusal, is a political act. How does it make sense that in order to protest against systemic violence and racism, we have to first be part of the very system of oppression we are criticizing?

The public refusenik letter is the first of its kind to go beyond the occupation and refer to the expulsion of Palestinians during the 1948 war:

We are ordered to put on the bloodstained military uniform and preserve the legacy of the Nakba and of occupation. Israeli society has been built upon these rotten roots, and it is apparent in all facets of life: in the racism, the hateful political discourse, the police brutality, and more.

The letter further emphasizes the connection between Israel’s neoliberal and military policies:

While the citizens of the Occupied Palestinian Territories are impoverished, wealthy elites become richer at their expense. Palestinian workers are systematically exploited, and the weapons industry uses the Occupied Palestinian Territories as a testing ground and as a showcase to bolster its sales. When the government chooses to uphold the occupation, it is acting against our interest as citizens– large portions of taxpayer money is funding the “security” industry and the development of settlements instead of welfare, education, and health.

Some of the signatories are expected to appear before the IDF conscientious objectors’ committee and be sent to military prison, while others have found ways to avoid army service. Among the signatories is Hallel Rabin, who was released from prison in November 2020 after serving 56 days behind bars. A number of the signatories also signed an open letter last June demanding that Israel stop the annexation of the West Bank.

‘Who are we actually protecting?’

Israelis have published a number of refusal letters ever since Israel took control of the occupied territories in 1967. While for decades the letters predominantly referred to opposing service in the occupied territories specifically, the last two Shministim Letters, published in 2001 and 2005, respectively, included signatories who refused to serve in the army altogether.

“The reality is that the army commits war crimes on a daily basis–this is a reality I cannot stand behind, and I feel I must shout as loud as I can that the occupation is never justified,” says Neve Shabtai Levin, 16, from Hod Hasharon. Levin, now in 11th grade, plans to refuse army service after graduation, even if it means going to prison.

“The desire not to enlist in the IDF is something I have been thinking about since I was eight,” Levin continues.

I did not know there was an option to refuse until around last year, when I spoke to people about not wanting to enlist, and they asked me if I was planning to refuse. I began to do some research, and that’s how I got to the letter.

Levin adds that he signed the letter “because I believe it can do good and hopefully reach out to teenagers who, like me, do not want to enlist but do not know about the option, or will raise questions for them.”

Shahar Peretz, 18, from Kfar Yona, is planning on refusing this summer. “For me, the letter is addressed to teenagers, to those who are going to enlist in another year or those who have already enlisted,” she says.

The point is to reach out to those who are now wearing uniforms and are actually on the ground occupying a civilian population, and to provide them with a mirror that will make them ask questions such as ‘who am I serving? What is the result of the decision to enlist? What interests am I serving? Who are we actually protecting when we wear uniforms, hold weapons, and detain Palestinians at checkpoints, invade houses, or arrest children?’

(article continued in right column)

Question related to this article:

Is there a renewed movement of solidarity by the new generation?

How can a culture of peace be established in the Middle East?

(article continued from left column)

Peretz recalls her own experiences that changed her thinking around enlistment:

[My] encounter with Palestinians in summer camps was the first time I was personally and humanly exposed to the occupation. After meeting them, I realized that the army is a big part of this equation, in its influence over the lives of Palestinians under Israeli rule. This led me to understand that I am not prepared to take a direct or indirect part in the occupation of millions of people.

Yael Amber, 19, from Hod Hasharon, is mindful of the difficulties her peers may encounter with such a decision.

The letter is not a personal criticism of 18-year-old boys and girls who enlist. Refusing to enlist is very complicated, and in many ways it is a privilege. The letter is a call to action for young people prior to enlistment, but it is mainly a demand for [young people] to take a critical look at a system that requires us to take part in immoral acts toward another people.

Amber, who was discharged from the army on medical grounds, now lives in Jerusalem and volunteers in the civil service.

I have quite a few friends who oppose the occupation, define themselves as left-wing, and still serve in the army. This is not a criticism of people, but of a system that puts 18-year-olds in such a position, which does not leave [them] too many choices.

While conscientious objection has historically been understood as a decision to go to prison, the signatories emphasize that there are various methods that one can refuse, and that finding ways to eschew military service can itself be considered a form of refusal. “We understand that going to jail is a price that not everyone has the privilege of paying, both on a material level, time, and criticism from one’s surroundings,” Amber says.

‘Part of the legacy of the Nakba’

The signatories note that they hope the political atmosphere created in recent months by the nationwide anti-Netanyahu protests–known as the “Balfour protests” for the street address of the Prime Minister’s Residence in Jerusalem–will allow them to talk about the occupation.

“It’s the best momentum,” says Amber. “We have the infrastructure of Balfour, the beginning of change, and this generation is proving its political potential. We thought about it a lot in the letter–there is a group that is very interested in politics, but how do you get them to think about the occupation?”

Levin also believes that it is possible to appeal to young Israelis, particularly those who go to the anti-Bibi protests.

With all the talk about corruption and the social structure of the country, we must not forget that the foundations here are rotten. Many say the military is an important process [Israelis] go through, that it will make you feel like you are part of and contributing to the country. But it is not really any of these things. The army forces 18-year-olds to commit war crimes. The army makes people see Palestinians as enemies, as a target that should be harmed.

As the students emphasize in the letter, the act of refusal is intended to assert their responsibility to their fellow Israelis rather than disengage from them. “It is much more convenient not to think about the occupation and the Palestinians,” says Amber.

[But] Writing the letter and making this kind of discourse accessible is a service to my society. If I wanted to be different or did not care, I would not choose to put myself in a public position that receives a lot of criticism. We all pay a certain price because we care.

“This is activism that comes from a place of solidarity,” echoes Daniel Paldi, 18, who plans to appear before the conscientious objectors’ committee. “Although the letter is first and foremost an act of protest against occupation, racism, and militarism, it is accessible. We want to make the refusal less taboo.” Paldi notes that if the committee rejects his request, he is willing to sit in jail.

“We tried not to demonize either side, including the soldiers, who, in all of its absurdity, are our friends or people our age,” he notes.

We believe that the first step in any process is the recognition of the issues that are not discussed in Israeli society.

The signatories of the latest Shministim Letter differed from previous versions in that they touched on one of the most sensitive subjects in Israeli history: the expulsion and flight of Palestinians during the Nakba in 1948. “The message of the letter is to take responsibility for the injustices we have committed, and to talk about the Nakba and the end of the occupation,” says Shabtai Levy.

It’s a discourse that has disappeared from the public sphere and must come back.

“It’s impossible to talk about a peace agreement without understanding that all this is a direct result of 1948,” Levy continued.

The occupation of 1967 is part of the legacy of the Nakba. It’s all part of the same manifestations of occupation, these are not different things.

Adding to this point, Paldi concludes: As long as we are the occupying side, we must not determine the narrative of what does or doesn’t constitute occupation or whether it began in 1967. In Israel, language is political. The prohibition against saying ‘Nakba’ does not refer to the word itself, but rather the erasure of history, mourning, and pain.

(Thank you to Azril Bacal for sending this article to CPNN.)